by Robert E. Hunter

-

“Then we’ll have done all we can.”

“Very heartless.”

“It’s safer to be heartless than mindless. History is the triumph of the heartless over the mindless.”

Yes, Prime Minister.

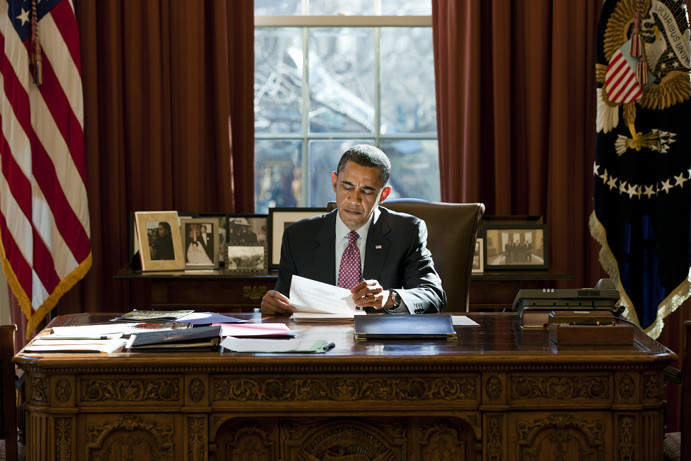

President Barack Obama, it is said, has painted himself into a corner with his repeated statements that the use of chemical weapons by the Assad government will be a “game changer” or cross a “red line.” The difficulty of definitions has produced what must have been one of the most ambiguous letters ever to be put on White House stationery. It came as a response to a demand from two US Senators about presidential policy in the event of such weapons use.

More accurately, however, the president can be said to have painted himself into a corner with Syria on two occasions, initially as early as August 2011, and repeated since, by declaring that “Assad must go.”

Of course, Assad has not gone, thus demonstrating once again the first rule of being US President: never call for something, especially in a simple declaratory sentence, if you are not prepared to follow through and make it happen.

This recitation is not meant to be an attack on the US president. It is an introduction to what has to be a genuine dilemma, indeed, a series of dilemmas, which come in several forms.

Syria’s Future

The first dilemma regards the potentiality of a positive outcome in Syria. Assad and company are engaged in the massive slaughter of their own people, which, along with those killed by the rebels, numbers more than 70,000 by a recent (likely conservative) count, plus the creation of more than a million refugees. There is meanwhile no resolution in sight of what has become a full-scale civil war.

Let us assume that Assad is killed (or decides to seek a safe haven) tomorrow. What then? It is a vast stretch of the imagination to believe that the killing would then stop.

What is happening in Syria is radically different from what happened in the so-called “Arab spring” in Tunisia, Egypt, or even Libya. This is not primarily a matter of whether a leader who stayed too long and was too repressive will go; but whether a particular minority will continue to be able to dominate the rest of the population, or, with “regime change,” whether there will be a bloody free-for-all competition for power. None of the other three regime changes were about that.

More relevant is what happened in Iraq, when the US and partners, by invading in 2003, overturned centuries of admittedly unjust domination of a majority (Shi’ite) by a minority (Sunni). Or what is happening, or rather not happening, in Bahrain, where the situation is just the reverse but has been kept in check by military power, much of which has been applied by neighboring Saudi Arabia, with the US, concerned about its base in Bahrain for the Fifth Fleet, at best “turning a blind eye.”

It’s therefore hard to see what the United States, or any combination of outsiders, could usefully do — not to help overthrow Assad and his Alawite-dominated military (that can be done) — but to help “shape” a future in Syria that won’t lead to even more bloody chaos before something approaching “stability” could ensue. Even if that were possible, it would likely take the form of a new suppression, but by the majority (Sunni) over various minorities.

Public Opinion

The second dilemma — perhaps it should be first — is related to whether the American people are ready and willing to see the US engaged in yet another Middle East war. The answer (“No”) is clear, but so far policy is not — hence the dilemma.

There should be no indulgence in the nonsense that all could be accomplished by providing more lethal arms to the rebels, imposing a no-fly zone, or using air power directly. That would be relatively sterile in today’s military taxology, but even if/when successful, it leads back to the first dilemma. And if unsuccessful, the US would then be called upon to do what, in current jargon, is called “boots on the ground” — that is, invasion. There should be no nonsense, however, about the US being able, as in Libya, to “lead from behind.” Even though the British and the French (the latter was the former mandatory power in Syria after World War I) would like to see something done, they are this time ready to hold the US coat, but not lead themselves.

To his credit, the president so far has been wary of getting more deeply engaged, presumably due to a combination of his awareness of the two dilemmas above, the second of which (US public opinion), if ignored, would surely take attention away from what he clearly sees as his legacy: repairs to the heavily-damaged US economy (and the global financial system) and his historical goal, which can be summarized in a few simple words: the promotion of equality in American society.

Regional Context

The third dilemma derives from the manner in which the conflict in Syria began. It did have domestic roots (as in Tunisia, Egypt and Libya), but it also had external causes and active agents, notably a desire by leading Sunni states (Saudi Arabia, the UAE, Qatar and to a lesser degree, Turkey) to right the informal and rough regional “balance of power” between them and Shi’a states that was so heavily upset by the US invasion of Iraq. This came after the spread of the “disease” from revolutionary Shi’a Iran had both been almost entirely contained in the region and had most of its fires banked at home. Some Sunni states still fear contagion, however, notably Saudi Arabia, where oil lands are heavily concentrated in Shi’a territories (hence Riyadh’s desire to get rid of the Alawite rule in Syria).

So here it is: an already slow-rolling civil war across the region, pitting Sunnis versus Shi’as, but only in part about religion, is also about competitions for power. In this case, it’s an essentially four-cornered competition among Iran, Saudi Arabia, Israel and Turkey, the first three of which have as much to do in fueling the current confrontation with Iran as does its nuclear program.

Would the overthrow of the Assad regime cause this regional civil war to intensify? Or would it lead to a new, informal balance among religious groupings that would be reasonably “stable,” whatever that means in today’s roiling Middle East? It would take a Dr. Pangloss to argue the case for stability over more competition and even less stability and predictability about the future of inter-state relations and internal developments.

Non-governmental Actors

Dilemma number four flows from the above. As the civil war has continued and intensified, Sunni Islamist militants, including elements of al-Qaeda, Wahhabis and Salafists, have increasingly become engaged. That should be no surprise. These groups batten on conflict, especially a conflict with intense emotion and deep-seated religious inspiration. Thus even with Assad gone — perhaps by magic wand tomorrow — would the outcome of the civil war be ruled by a Sunni strongman, pacifying the country by force? Or solidification of another base for continuing terrorist operations by some of our and our allies’ worst enemies?

Israel’s Circumstances

One argument for getting rid of Assad and his Alawite-dominated regime is that this would help deprive the Lebanese Hezbollah of its rear base, which provides political support and a supply route for Iran as it seeks to counter pressure from the US and Israel. But at what (potential) price would Iran be thus incommoded?

Since 1974, Israel existed uneasily but still reasonably comfortably with Assad père et fils, as both countries learned to live with one another. Their mutual frontier along the Golan Heights was so stable that Israel could even invade Lebanon (twice) and attack a Syrian nuclear reactor without a military response. Now that modus vivendi is very much in jeopardy.

Indeed, for many months after the Syrian civil war started, Israel was clearly at least ambivalent about whether Assad’s departure was in Israel’s best interest. It now seems to have passed that point, but even that is not entirely clear.

What should be clear, however, is that if Assad goes and there is an intensifying civil war, with “free play” for Islamist radicals of the worst stripe — the kind that have inspired and in many cases conducted the killing of Americans in Afghanistan — the US will be called upon to be even more robust in support of Israel’s security.

Would that mean US forces on the Golan Heights? Israel has never wanted this direct military engagement from the US, but the need for extra commitments to Israel’s security would be very likely. Furthermore, the argument that Iran would be the big loser from Assad’s departure might even be turned on its head. The balance in Tehran could be tipped toward those who argue that Iran should get nuclear weapons in order to deter a burgeoning list of enemies.

Strategy

Then a final dilemma: the US desire to “pivot” to Asia. But at least some refocusing of policy and military assets will not be as easily done as has been hoped with the end of the Iraq War, the winding down of the Afghanistan War and the efforts to keep Iran from crossing either US or Israeli red lines on its nuclear program.

With Syria and its interlocking dilemmas, plus other continuing challenges in the region, the US will not be able to rid itself of a major security role in the Middle East anytime soon, even if it (rightly) promotes an international approach to even some of these dilemmas, no matter how much oil and gas is eventually produced in the continental US.

It is probably — but not certainly — too late to find some means whereby Assad could stay in power but with genuine power-sharing that would radically reduce the prominence of the Alawites without leaving them to be victimized as they have victimized other Syrians for so long. Of course, power-sharing efforts almost always fail in mechanical approaches to foreign policy, so perhaps that was never a real option, a triumph of Western “hope over experience.”

So what is to be done at this juncture of “no good options?” The best to be hoped for now is for President Obama to keep his nerve (backed by the US military leadership) and continue resisting attempts to drag the US even more deeply into Syria. At the same time, the US must avoid the temptation to perceive another looming chance to experiment with “nation building”; Iraq and Afghanistan should have inoculated us against that.

As a cardinal principle, the US should internationalize whatever is done — by the United Nations, NATO, the European Union and Arab League — and not regard Syria as a test of US “leadership,” as asserted in the aforementioned White House letter (“strengthen our leadership of the international community.”) It should put out the word in very clear terms to other states in the region to stop meddling in Syria, and in particular, to rein-in their nationals who are engaged in spreading Islamist militancy in Syria (and elsewhere), with both ideas and arms.

Finally, the US needs to begin seeing the region as a whole, not as a series of bits and pieces, loosely connected to one another, with Washington attempting only “to put out fires” here and there, while pretending that the whole region is not potentially ablaze. The president has to recruit for his administration the very best people to think strategically and this time plan ahead. They must understand that the US has to create consistent and coherent policies for the entire region that have some chance of success for the long haul.

I agree with most of the author’s opinions, but would like to make a correction, that in Iraq (prior to 2003 invasion) the Sunni minority ruled over the Shia majority, exactly like in Bahrain is currently, not in reverse, as the author states.

Mr Hunter,

I am not going to engage you on the humanistic point of view since obviously you are lacking any of it with your pseudo intellectual dissertation .

I will not engage you about what America stands for in the world.

I will engage you on something you might understand. If the present regime in Syria wins, you would be creating a regional power under the guise of Iran which would include Iraq, Syria and Lebanon for the time being. We are talking about Pasdaran on the physical frontiers of Israel.

Then explain to me how such a regional power could further the interests of the United States and Europe in the short and long run.

I do agree with you that the president should recruit in his administration better people.

Tony, no reason to get so hostile and snappy. If you disagree with the article so vehemently then maybe you should write one yourself.