by Jim Lobe

via IPS News

Ten years after reaching the height of their influence with the invasion of Iraq, the neo-conservatives and other right-wing hawks are fighting hard to retain their control of the Republican Party.

That fight was on vivid display last week at the Conservative Political Action Conference (CPAC) here where, as the New York Times observed in a front-page article, the party appeared increasingly split between the aggressively interventionist wing that led the march to war a decade ago and a libertarian-realist coalition that is highly sceptical of, if not strongly opposed to, any more military adventures abroad.

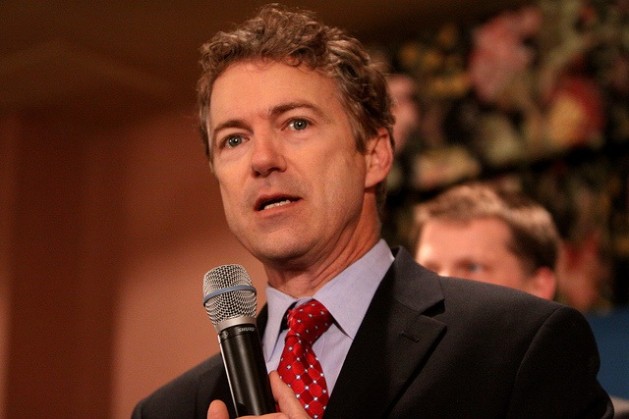

The libertarian component, which appears ascendant at the moment, is identified most closely with the so-called Tea Party, particularly Kentucky Sen. Rand Paul, whose extraordinary 13-hour “filibuster” against the hypothetical use of drone strikes against U.S. citizens on U.S. territory on the Senate floor last week made him an overnight rock star on the left as well as the right.

McCain dismissed Paul and his admirers as “wacko birds on the right and left that get the media megaphone” and charged that Republican senators who joined Paul – among them, the Senate Republican Leader, Mitch McConnell – during his oratorical marathon should “know better”.

But, beyond drones, the party is deeply divided between deficit hawks, including many in the Tea Party who do not believe the Pentagon should be exempt from budget cuts and are leery of new overseas commitments, and defence hawks, led by McCain and Graham.

The split between the party’s two wings, which have clashed several times during Barack Obama’s presidency over issues such as Washington’s intervention in Libya and how much, if any, support to provide rebels in Syria, appears certain to grow wider, if for no other reason than deficit-cutting will remain the Republicans’ main obsession for the foreseeable future.

For now, it appears that the deficit hawks have the upper hand, at least judging from the reactions so far to the Mar. 1 triggering of the much-dreaded “sequester” which, if not redressed, would require the Pentagon to reduce its planned 10-year budget by an additional 500 billion dollars beyond the nearly 500 billion dollars that Congress and Obama had already agreed to cut in late 2011.

“Indefensible,” wrote neo-conservative chieftain Bill Kristol in his Weekly Standard about Republican complacency in the face of such prospective cuts in the military budget.

“(T)he Republican party has, at first reluctantly, then enthusiastically, joined the president on the road to irresponsibility,” he despaired.

The great fear of the neo-conservatives is that, given the country’s war weariness and the party’s focus on the deficit, Republicans may be returning to “isolationism” – a reference to the party’s resistance to U.S. intervention in Europe in World War II until the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor in Dec 1941.

Just as Adolf Hitler’s subsequent declaration of war silenced the isolationists, the rise of the Soviet Union after the war – and its depiction as a global threat – ensured that the party remained committed to a hawkish foreign policy over the next 45 years.

The end of the Cold War, however, created a new opening for those in the party – particularly budget-conscious, limited-government conservatives – who saw a big national security establishment with major overseas commitments as a threat to both individual liberties and the country’s fiscal health.

Thus, many Republican lawmakers went along with significant cuts in the defence budget that began during the George H.W. Bush administration. The party also split over a number of military actions in the 1990s, including Bush’s “humanitarian” intervention in Somalia, and Bill Clinton’s campaigns in Bosnia and later Kosovo.

Republican lawmakers also strongly opposed Clinton’s dispatch of troops to Haiti to restore ousted President Jean-Bertrand Aristide in 1994.

Indeed, it was during this period that the neo-conservatives allied themselves with liberal interventionists in the Democratic Party to help prod an initially reluctant Clinton to intervene in the Balkans.

And in 1996, Kristol and Robert Kagan co-authored an article in Foreign Affairs entitled “Toward a Neo-Reaganite Foreign Policy,” that was directed precisely against what they described as a drift toward “neoisolationism” among Republicans.

The following year, they co-founded the Project for the New American Century (PNAC), whose charter was signed by, among others, eight top officials of the future George W. Bush administration, including Dick Cheney, Donald Rumsfeld, and Paul Wolfowitz.

The new group was not only to serve as an anchor for Republicans who supported its founders’ vision of a “benevolent (U.S.) hegemony” in world affairs based on overwhelming military power, but also as a lobby for ever higher defence budgets and “regime change” in Iraq, as well as a more confrontational relationship with China which it saw as the most likely next challenger to a U.S.-dominated global order.

Occupying key positions in the new Bush administration, these hawks took full advantage of 9/11 and reached their greatest influence when, exactly 10 years ago this week, the U.S. launched its invasion of Iraq to “shock and awe” the rest of the world into compliance with the new order.

And while a tiny minority of Republicans, including notably, Paul’s father, Rep. Ron Paul, and Sen. Chuck Hagel – who was just confirmed as Obama’s defence secretary despite an all-out neo-conservative campaign to defeat him – voiced strong reservations about the war at the time, the overwhelming majority of the party enthusiastically embraced it, sealing the hawks’ own domination of the party.

Ten years later, however, that domination is increasingly under siege, not only because of the growing national consensus that the Iraq invasion was a major strategic debacle, but also because of the increasing popular concern – noted in a number of major polls over the past six months – that Washington simply can no longer afford the kind of imperial vision the hawks have promoted.

And the fact that younger voters – so-called millennials, aged 18-29 – are, according to the same polls, especially repelled by that vision can only strengthen those in the party calling for a more restrained foreign policy.

Still, true to their nature, the hawks will not give up without a fight, and their hold on the party remains strong, as demonstrated most recently by the fact that only four Republican senators, including Paul, voted to confirm Hagel, a Republican realist, in his new post.

“It is way too early for budget hawks to declare victory,” noted Chris Preble of the libertarian Cato Institute on foreignpolicy.com last week. “The neocons won’t go down without a fight, and they will have other chances in the months ahead to ratchet the Pentagon budget back up to unnecessary levels.”

Photo: Kentucky Senator Rand Paul speaking to supporters in New Hampshire. Credit: Gage Skidmore/CC-BY-SA-2.0