by Jim Lobe

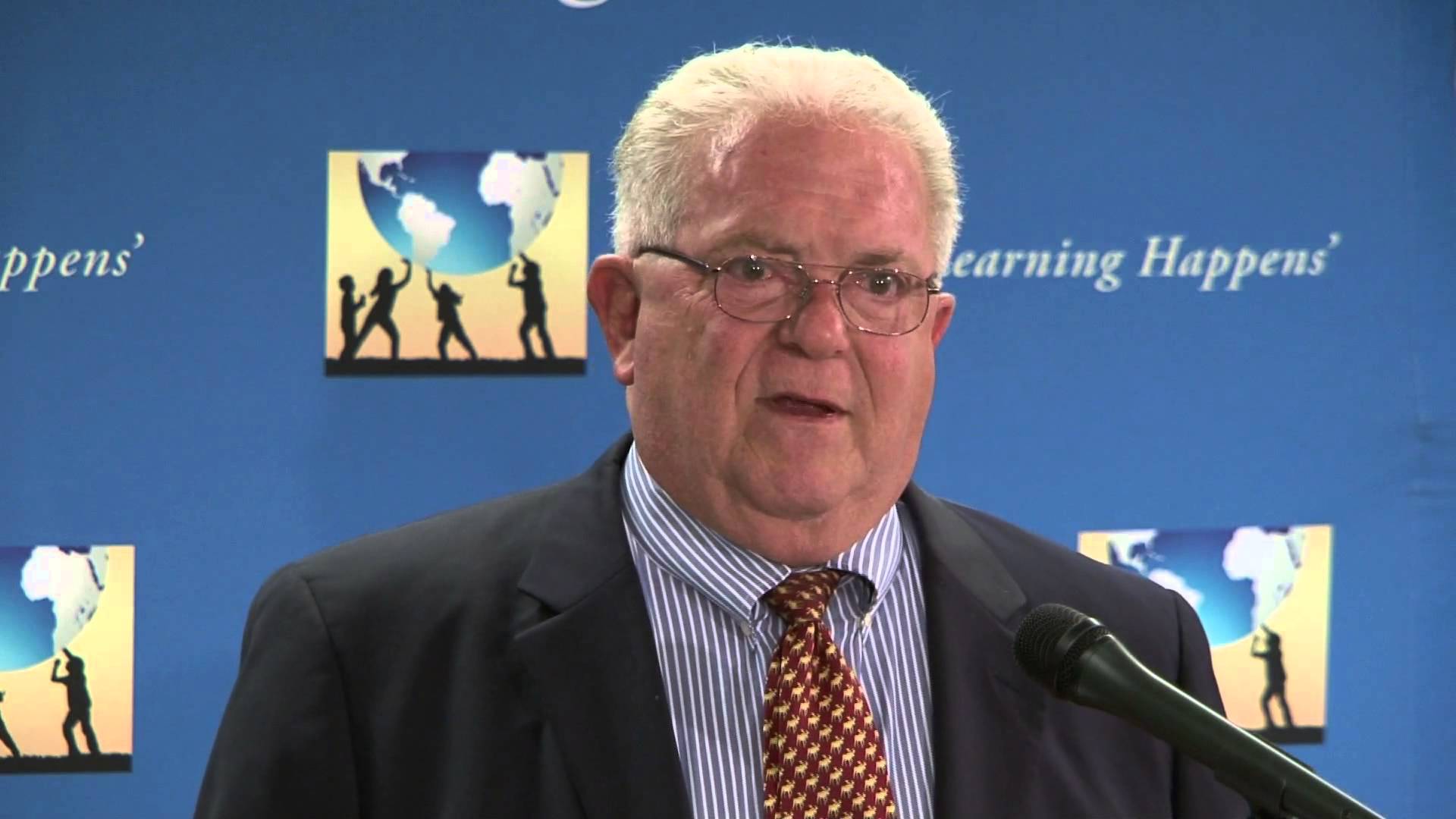

The following are excerpts from a telephone interview conducted late last week with Amb. Chas Freeman, Jr. (ret.) regarding the latest developments between Iran and Saudi Arabia, in particular. Freeman, who served as U.S. ambassador (1989-1992) to the Kingdom during the first Gulf War and has maintained numerous high-level contacts there since, served in a variety of other positions in the U.S. Foreign Service. He was Richard Nixon’s interpreter during his historic 1972 visit to China and the principal deputy assistant secretary of state for African affairs during which he was the main U.S. delegate in multi-party negotiations leading to the independence of Namibia and the withdrawal of Cuban troops from Angola. A past president of the Middle East Policy Council and lifetime director of the Atlantic Council, he was chosen by then Director of National Intelligence Dennis Blair to chair the National Intelligence Council in 2009 but withdrew his name from consideration after a major campaign by neoconservatives and other key leaders associated with the Israel lobby against his nomination.

The interview covers a number of issues, including the origins of Saudi disillusionment with Washington during the George W. Bush administration and its evolution in subsequent years; what Freeman sees as Riyadh’s intentions in carrying out the mass executions, including that of Shekh Nimr Baqir al-Nimr, earlier this month; the importance of rapprochement between Iran and Saudi Arabia; the Saudi-led military campaign in Yemen; and the possibilities for greater international cooperation against the Islamic State (ISIS or Daesh) and similar extremist Salafi groups.

Jim Lobe: What do you see the Saudis doing now?

Chas Freeman: The Saudis have gone off on their own. They’ve come to that position through a process of evolution over the course of this century beginning with George W. Bush’s decision in the spring of 2001 that the United States could not be more in favor of peace [between Israel and the Palestinians] than the parties and that the peace process should therefore be dropped.

In dropping the peace process, he deprived the Saudis and other Arab friends of the United States of the cloak that they had used to justify their relationship with Washington to partisans of the Palestinians. In other words, the Saudis had previously claimed, “Well, the Americans may be doing all sorts of bad things with the Israelis but they are the only ones who can help us reach a just resolution of this conflict.” That had been the argument, but Bush basically pulled the rug out from under them.

And that coincided with [former Israeli Prime Minister Ariel] Sharon going into Jenin [during the second intifada] despite Bush’s efforts to dissuade him. That showed the Saudis and others that the United States could not or would not restrain the Israelis and thus could no longer be considered their protector from the Israelis. That devalued the U.S. role as a security guarantor. Everything that has happened in the following 15 years has driven another nail in the coffin of Saudi reliance on the United States as a protector.

After that, in the spring of 2001, [then-Crown Prince] Abdullah declined an invitation to the White House, confiding privately that he couldn’t afford to be seen in Bush’s presence. Then, a few months later, in August 2001, he sent a letter to Bush saying that Saudi Arabia and the United States had come to a parting of the ways and that there needed to be separation and maybe even a divorce. That alarmed Washington enough to compel the Bush administration to release [Secretary of State] Colin Powell from his fetters and give him permission to reengage on Israel-Palestine issues.

But then 9/11 happened, and there was an immediate divergence between the U.S. and Saudi Arabia. The U.S. reaction was self-righteous—“they hate us because of our values,” not as a result of the impact of our actions. The Saudi reaction came in a speech in Muscat by Abdullah in which he said that we [the Saudis] bear responsibility for what went wrong and need to correct our problems. So, on the Saudi side, you had introspection and contrition and on the U.S. side you had assertive self-righteousness and rising Islamophobia.

Ever since then, we’ve seen both those trends and the gap in perceptions they represent continue. On the Saudi side, contrition has turned into resentment against what they see as American betrayal of a previously professed friendship coupled with slander of Muslims. This has culminated in the statements of Donald Trump (who has really made it impossible for anyone in the Arab world to say a kind word about the American people).

Then you had the invasion of Iraq, the morphing of a punitive mission in Afghanistan into a pacification campaign apparently aimed at keeping militant Muslims from a role in running their country, and various instances of U.S. enthusiasm for Israeli bombings of Gaza or Lebanon. The result of all of this has been the appearance of an American campaign against Islam as well as the steady empowerment of Iran as the regional hegemon: the installation of a pro-Iranian regime in Baghdad, the lack of any response to Assad’s overtures to reduce his dependence on Iran, the support for Israel’s actions in Lebanon that empowered Hezbollah as the main political force there, U.S. ambivalence toward the unrest in Bahrain and a whole a series of other events. The worst of these—from the Saudi perspective—was America’s unwillingness to stand by [Egyptian leader Hosni] Mubarak, who had been our protégé. That convinced the Saudis that the United States was not just unreliable as a friend, but treacherous.

So the Saudi reaction to American policy in this century has been, first, an effort to find an alternative to the United States as protector. The Saudis discovered that there is no such alternative. So they sought to dilute their perceived overreliance on the United States by developing relations with other powers like China, India, Russia, Brazil, and Germany. They discovered the limitations of what was possible in that regard. Finally, more recently, they have apparently decided that they have no real choice but to rely on themselves and go off on their own.

So now we come to most recent events. I think they occurred for several reasons. First, the Saudis decided to increase the priority they assign to dealing with Daesh. To that end, they announced the formation of a so-called “Islamic Alliance,” which is a loose coalition in the process of becoming something, though it hasn’t yet really done so. It is an effort to form a coalition to organize the Sunni world against Daesh and also, frankly, against Iran.

The Al-Saud also felt they needed to send a strong message to their own population, especially the Salafi element of it (which they fear might sympathize with Daesh). They wanted to put the fear of God in their own Salafi extremists by executing a large number of them. At the same time, to demonstrate to their more moderate Salafi constituency that this was not a turning away from Salafism, but rather a decision directed at terrorism, they included four Shia among the 47 who were executed. One of these was Sheikh Nimr Al-Nimr, an Iranian-trained cleric with a history of violent speech, if not violent action, against the ruling family. (The Saudis claim that he had some association with Hezbollah operations in the Eastern Province.)

This was both a step-up in the Saudi war on terror and yet another step in a staged declaration of independence from the United States. What it was not was a signal to Iran or an effort to provoke an Iranian reaction. The Saudis, like everybody else, make their policies mainly by reference to domestic, not foreign opinion. So when the Iranians reacted in what was an unfortunately familiar way—by invading and burning diplomatic and consular facilities—the Saudis got a bonus, which was a demonstration of Iranian barbarism that played very well at home in Saudi Arabia and, to a considerable extent, internationally.

When a host country doesn’t protect diplomats, the normal reaction is to break relations. I’m sure that neither side planned this outcome but it’s entirely understandable, as we here in the United States can attest. After all, we haven’t had relations with Iran for decades for precisely that reason.

I see a lot of speculation among the punditry, especially the Iranian-aligned punditry, that somehow the Saudis carried out the execution of Sheikh Nimr to provoke Iran. Although Iran was indeed provoked, I think that was an unexpected benefit, rather than a motivation, for the Saudis.

This set of developments, of course, greatly complicates any American rapprochement with Iran. No doubt many Saudis think this is a good thing. But peace in the region requires some measure of rapprochement between Saudi Arabia and Iran. And the United States needs to have a relationship with Iran of some sort if it is to play an effective role in a region where Iran is a major actor, as it is in Iraq, in Syria, in Lebanon, in Bahrain, and now in Yemen. So some Saudis are probably very happy about the additional difficulties that now complicate an opening between the United States and Iran that they would prefer not to happen. I don’t share their pleasure in this. I think they have not done a favor to either themselves or to us with this result.

To sum up: U.S.-Saudi relations have evolved from a strong partnership to wary cooperation at increasing distance. These latest events are merely confirmation of that trend.

Lobe: How does the conflict in Yemen figure into this?

Freeman: From the beginning, the Saudi bombing of Yemen has resembled nothing so much as the Israeli actions in Gaza; that is, an exercise in military intimidation with no achievable political objective attached to it. You cannot install or restore a government from the air, and therefore, although air attacks may intimidate Yemenis, they are not going to achieve the announced Saudi objective. There’s much destruction and no real gain for Saudi Arabia in its war in Yemen.

I think the United States has supported the Saudi war for two reasons: 1) it doesn’t want to break with the Saudis, and therefore support is the better part of valor; and 2) American arms manufacturers are making a bundle off the war. And, of course, in the background, there’s the desire not to have the Saudis bolt from their acquiescence to the Iran nuclear deal. But the Saudis’ problem with the deal has been its implied recognition of the prestige and power of Iran, not its nuclear aspects. And their apprehension has a sound basis.

Lobe: So, with this latest contretemps, where are we now in the region?

Freeman: In addition to complicating U.S. rapprochement with Iran, the latest events complicate U.S. diplomatic efforts to make peace in Syria. These are belated and still rather inchoate. They came about mostly because the Russians made a peace process necessary.

The Saudis say they will go to the next meeting [in Geneva] with the Iranians. That’s good. It is also, in a sense, an illustration of the new era in which we find ourselves—in which the statement, “You are either with or us against us” is an absurdity, and countries can be against each other for many purposes, even as they work together on many others. That’s the world in which now live and in which we’re going to have to learn to live.

Lobe: There has been some speculation about these latest moves showing weakness or desperation on the part of the Saudis.

Freeman: I take issue with David Ignatius’ thesis that the Saudis are doing what they’re doing out of fear. I think they are instead showing frustration at their inability to get support from others, especially the United States, for their main objectives in response to the serious challenges they face. Domestically they’re not fearful but determined to nip in the bid any signs of dissent that might lead to unrest, particularly from the Shia. But they are also determined to head off any sympathy for Daesh from the Salafi majority in their society.

In dealing with Daesh, they are trying to apply the three-tier approach that they used domestically to the same problem abroad. That approach includes, first, the refutation of the theology, basically by rebutting the notion that terrorism is consistent with any legitimate version of Islam; second, reform of potential miscreants by exerting moral and social pressure on them and persuading them it would be wrong for them to become terrorists; and, third, executing anybody who commits an act of terrorism, both to eliminate the threat they pose and to deter others from following their example.

It appears that the purpose of the “Islamic Alliance” is to extend this approach to the broader Muslim world. And that is an opportunity, I think, for the United States and others.

We have been contemptuous of international law for more than a decade. Yet, this is an issue that unites the international community and the [UN] Security Council, all of whose members share the same desire to contain and eventually eliminate Daesh and its ilk. The Islamic Alliance is an opportunity for the UN to authorize and enable a division of labor against Daesh, in which non-Muslim powers would provide, as necessary, the intelligence, logistical, material, munitions, and training support, but Muslims would bear the burden of ideological refutation, reform, law enforcement, and boots on the ground.

If we went to the UN, this would have the following advantages: we would restore international law as the basis of international action against terrorism; we would unite the international community, including its Islamic element; and we would enable the writing and conclusion of an international convention on terrorism to criminalize it as was done with piracy. (It’s astonishing that we still don’t have an internationally agreed definition of terrorism.) We could try to write model legislation for passage at the national level. This would harmonize treatment of people who commit terror and boost international cooperation. There’s an opportunity here for someone with vision, which means someone other than those now running for president in our country.

For the Saudis, Enemy Number One is still Iran, and Assad is seen as the pawn of Iran. But, at the same time, the Saudis have raised their sense of urgency about dealing with Daesh and stepped up their efforts to do so. We should welcome that.

In these circumstances, I think it would be a mistake to castigate the Saudis, as some commentators now are urging. If you put them in the enemy category, what have you gained? Do you think you will increase their willingness to cooperate with you by heaping contumely upon them? I think quite the opposite would be the case. It would be yet another case of American foreign policy by tantrum, this time directed at the Saudis. I don’t think this would be a wise course.

Lobe: Should the U.S. be doing anything to get reduce tensions between Iran and the Saudis at this point?

Freeman: I don’t think the United States is in a position to influence that positively. We don’t have a relationship with Iran; we don’t have a cordial relationship the Saudis. We’re not in a position to broker anything but discord. The prospect for a rapprochement would probably be improved by our stepping back.

We have a habit of creating moral hazard in the region by enabling self-destructive behavior by countries regardless of their interests or ultimately our own. If we didn’t offer to do everything for everyone or provide unconditional backing for the region’s major actors—whether Saudi Arabia or Israel or Egypt—the chances would improve that they might feel obliged to make the hard choices they should make to serve their own interests. There are many decisions they should make that are politically difficult for them. They won’t make them if we give them an excuse not to.

Moral hazard arises when you assume the risks of failure for other people. When you do that you encourage them to ignore risks and make decisions that are against their real interests. That is injurious to them and to us. We need to change our foreign policy game to encourage others to act in their own self-interest.

Photo: Chas Freeman, Jr.

Mr Chassman has answered all questions to the diplomatic gymnastics ,about turn and the somersaulting of Saudis in the very opening of this article – Sauidis could no longer use the ruse that Bush AKA American would continue to publicly pay lip service to Israel Palestine . Sudden loss of this plank removed the legitimacy of the Saudis or at least thats what sauids feared. They never had much legitimacy more than Saddam or Burmese junta ever had .

Sauids and the Muslim have paid dearly for this decades long sham American support to I-P conflicts – from Afghanistan,to Balkans,to Iraq war to Kosovo back to Iraq and Libyan war. Muslim have earned hatred in Serbia,Russia,India,China and have been beaten to the pulp in Ethiopia ,Burma and Xinxiang . Despite these naked aggressions on Muslim, Sauids did not change its courses in Kashmir,Afghanistan, on Russia and China until now .

But these countries are not stupid the way the Wahabi-Salafi – and all varieties of Islamic political ideology indoctrinated sheep from Indonesia to Pakistan to Nigeria are.

Saudis build mosques in Germany for the immigrants as if that is the most relevant crisis teh Muslim youths are facing within and outside of Saudi border .

I read somewhere that the Nigerian muslim king or Chief allowed British to plunder , spraed education among tribal indigenous forest dweller and also spread Christianity in exchange for his dynastic safety and total religious control on his muslim subjects . No one will miss much if Sauidi royal went the way the Nigerian king went with his harem.

IS it possible that the Israeli “attacks” on Gaza had anything to do with rockets daily falling in Israel from Gaza?

I think the US policy of realignment in the middle east is a correct one; surprisingly it started with George Bush (not the smartest US president). Unless the Middle Easterners learn that they should manage their affairs and live with each other somehow (without counting on US foreign aid and military support), that place will burn. We must stop supporting the Israeli policies as well as Saudi’s alike. They are both burden and we cannot afford that in the long term (they are like Cuba’s burden on the old Soviet Union — black holes sucking US human/policy energy US lives and treasures).

once again, Jim just dominates the interview–not; great job, let the kids handle the little stuff, but save your chops for the big fish. Thanks

The views expressed in this article shows good understanding of the situation in the Arab/Persian world. However, as an Arab born of Persian heritage, I would disagree of Ambs. Freeman with his statement, ” One of these was Sheikh Nimr Al-Nimr, an Iranian-trained cleric with a history of violent speech, if not violent action, against the ruling family. (The Saudis claim that he had some association with Hezbollah operations in the Eastern Province.)”. Sheikh Nimr never used threats in his speeches, fiery yes, but not threatening in the way of encouraging use of violence. He was a political opposition and there is no justification for chopping someone’s head because of that. Let us be civil and call a spade a spade. The Saudi govt. is tyrannical even if they are a US ally, which in itself is an anathema, given the US values are based on democracy which is totally in disagreement with the Saudi mentality. Thank you.