by Henry Precht

Thirty-five years ago this week, my wife and I were driving on a highway in Pennsylvania, coming from Parents’ Weekend at Colgate. I was in charge of Iranian affairs at the State Department and was passing the time trying to imagine new approaches that might help us normalize relations with Tehran’s distrustful revolutionary regime of clerics. I had just spent two weeks in the Iranian capital trying to find ways to ease tensions.

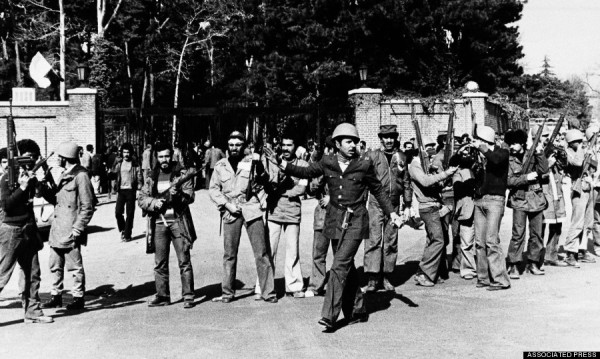

I turned on the radio at noon and heard that a group of students had seized our embassy, demanding that the Shah–then in the US for medical treatment–be returned to Iran for trial. “Now we’re in the soup,” I thought, knowing that only Ayatollah Khomeini could chase the students off the premises. Although no American official had ever met with him, we knew the ayatollah to be a bold, inflexible cleric, determined to construct an Islamic regime in Iran. Would he risk everything by confronting the US?

In fact, we learned later, his initial reaction was to “Get those kids out of there. Who do they think they are?” Then the students’ cause was adopted by radical clerics who persuaded them to stay indefinitely–rather than only through the weekend as they had planned. The radicals whipped up the usual “Death to America” mob who marched to Khomeini’s office. They changed his mind: he praised the students’ audacity, piety and courage. That wasn’t hard to understand: It was the students and clerics on one scale; the Shah and the US on the other. No contest!

The ordeal that was to last 444 days began with President Jimmy Carter’s sending Ramsey Clark on Air Force One to meet with Khomeini and present him with a presidential letter demanding the release of the hostages. I was sent along to explain the background to Clark. We were over the Atlantic when word reached us that Clark’s secret mission was reported on the evening TV news. The Iranians hadn’t granted him permission to come, however.

That permission came when we were flying over Spain but we were told that we could not land in a large plane; only a two-engine plane would do. (Were the Iranians fearful that a company of Marines would hop out and seize the capital?) Later, over Greece, clerical fears mounted and we were told that we might enter only on a commercial flight. Finally, when we reached Istanbul, the word was that we could not enter and no Iranian official could speak to an American. Clark moved into the American Consul General’s house and began his efforts to persuade Yasser Arafat to help. Deeply frustrating work, given the primitive state of the Turkish telephone system.

That episode was typical of events for over a year of bitter frustration: The Iranian prime minister and his group—practically the only officials we could talk to–resigned. The students opened Embassy files, read or misread documents and called us spies (some few were). We froze their bank holdings. They refused directives or pleas from the UN, the World Court, most other governments and many private organizations.

It’s past time to extract a few lessons from that crisis:

- The leadership on both sides was ignorant of realities on the other side–plenty of ideology, few facts.

- Know your enemies. We had missed chances to meet with Khomeini. Thus, he didn’t really know us and we didn’t understand him–we had no possibility of reaching and trying to influence him.

- There’s an adage in the Middle East that when two enemies can’t talk to each other, they should seek an intermediary. I suggested Syria and Algeria as radical regimes acceptable to Tehran. Mr. Cyrus Vance rejected Syria; Algeria would not help us until almost a year had passed. Then, emboldened, they truly made a difference to the success of negotiations.

- If you let a crisis drag on, you open the door to unforeseen dangers. Thus, sensing Iran weak, isolated and poorly led and equipped, Iraq invaded in September 1980. The two Iraq wars were a direct consequence.

- This crisis happened 35 years ago; it is high time to put it behind us and move on. Iran is a different country now. The Economist writes, “one reason why the relationship is so poisonous is that popular Western views of Iran are out of date to the point of caricature.” If Washington plays its cards wisely, over time Iran might be helpful to us in a crisis-ridden region we don’t fully comprehend.

#6: If you poison someone’s well, later on you can’t drink from that well yourself either.

I think Iranians are much better off today without the chance of normalizing relationship with the US at that time. Iran has suffered but at the same time, learned how to be self sufficient and technologically advanced. I think the country now has reached a point of self sufficiency in everything that the normalization of relationship with the US will not be harmful. The only reason the United States is now willing to deal with Iran is because they can’t keep Iran under rap and cannot change the government. ” if you cant beat them, join them”

Well Mike, I’ve read that there are still Jews who live in Iran, as well as a Couple of $billionaire brothers in Israel who trade with Iran on a continual; basis. Oh my goodness, I suppose that makes the Netanyahoo boys club feel a bit queasy? I believe now, after the Gaza turkey shoot, both the U.S. for refilling the ammunition spent, having seen Israel spit in its face again, as well as Europe who are getting fed up with the whole mess, may just be willing to censor Israel in ways that we haven’t seen in years. IMHO.