by Jim Lobe

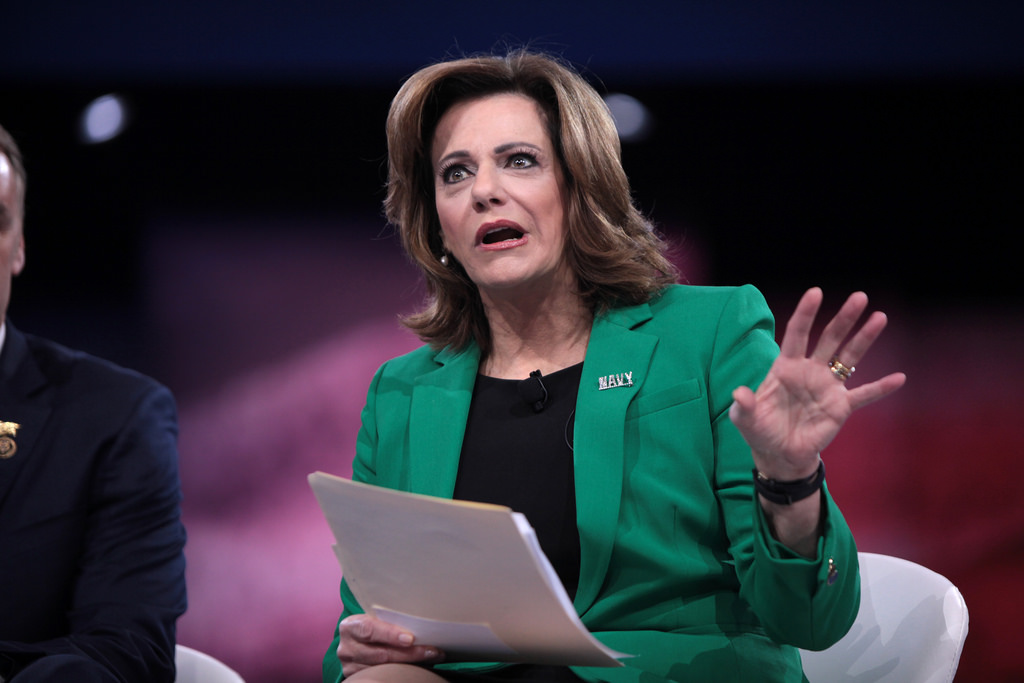

When retired Adm. Robert Harward rejected Donald Trump’s offer to succeed Gen. Michael Flynn as the president’s new national security adviser (NSA), a variety of sources reported that the general’s real reason was that he couldn’t pick his own staff. He would have been required to work with Stephen Bannon as Trump’s chief White House strategist, who finagled himself onto the Principals Committee of the National Security Council. Worse, his second-in-command would have been Flynn’s deputy NSA, K.T. McFarland, a former Fox News national-security commentator who distinguished herself at the cable station for, among other things, Islamophobia, Sinophobia, and conspiracy theories. Although Harward, a former Navy SEAL, publicly cited the familiar family and financial reasons for regretfully turning down a U.S. president, he was reliably reported to have privately told his friends that the package—mainly McFarland but presumably also some other political appointees on the NSC—offered by Trump constituted a “shit sandwich.”

Last night, the estimable Laura Rozen produced a string of tweets on the situation, the most notable of which read “contact says, Just was told Trump told KT McFarland to pick her new boss. She named Bolton. See where this goes.” If true, this would mean that Trump, whose family has reportedly developed close personal ties to McFarland over recent years, has delegated to the deputy NSA to choose the NSA, a bizarre arrangement to say the least. That John Bolton should be her favorite for the job, although not surprising in itself given her ideological tendencies, should, of course, scare the hell out of everyone, but let’s leave that until a final decision is made. (As noted by Greg Thielmann, the State Department’s former senior weapons of mass destruction (WMD) expert, if Trump is so riled by the intelligence community’s mistakes on Iraq’s WMD, he should be really, really outraged by Bolton’s heavy contribution to that fiasco.)

I generally avoid cable or any television news, so I had never seen McFarland on Fox. But I did witness her participation in the all-day “Passing the Baton” conference that took place at the U.S. Institute of Peace (USIP) on January 10, videos of which can be seen here. McFarland appeared on the last panel of the day, entitled “America’s Role in the World.” Moderated by Politico columnist Susan Glasser, the panel also included former undersecretary of defense for policy Michele Flournoy; former NSA under George W. Bush, Stephen Hadley; and top Hillary Clinton foreign-policy aide, Jake Sullivan.

I was deeply impressed by McFarland and left the presentation completely and irrevocably persuaded that she was totally unfit for the job. It wasn’t because of her ideological predispositions, which she didn’t address. Instead, she just struck me as the epitome of a ditz (I don’t mean to be sexist, but it seems appropriate in this case), a flibbertigibbet, an airhead. She blabbed on and on and on—often nonsensically—with the hoariest of clichés, non-sequiturs, circular reasoning, run-on sentences, and abrupt detours in mid-sentence. Bear in mind that the function of the deputy NSA is to ensure that the day-to-day operations of the NSC run smoothly. The person in that position also convenes and chairs the Deputies Committee from all relevant departments to discuss and decide on options for critical foreign-policy decisions, some of which are decided at the Deputies level and the most important of which are sent to the Principals for final presentation to the president. The post requires a sharp-as-a-tack strategic mind; organizational discipline; efficiency in preparation, discussion, and decision-making; verbal precision and coherence; and adherence to a process in which all relevant points of view are given due attention and weight. You should watch the video to see her range of facial and hand gestures—and to see that she is likely to fail at all the qualifications for the job. Under her leadership, I would imagine that these meetings would leave remotely competent participants in a state of utter frustration. Of course, rendering the Deputies Committee useless will only serve to reinforce the current pattern of ignoring the departments and centralizing more power in the White House’s upper reaches, specifically in Bannon’s office.

Because the video is long, and McFarland’s interventions are sporadic, I’ve taken the time to transcribe her remarks as best I can. She’s a very fast talker, so there may be a few individual words lost or missed or misunderstood, but I tried to be very careful. This transcript will give you a good idea of why I reached the harsh conclusions above. Note that some sentences don’t make grammatical or syntactical sense. That’s how she spoke. She is completely unfit for the job, and it’s terrifying to consider that she has veto power over the next NSA, let alone that she will choose him or her.

Question: Will Trump Represent Break with Previous U.S. Foreign Policy?

First of all, I want thank you for that question and tell you that I’m not going to answer it because my boss is sitting right here in the front row.[Laughs] Gen. Flynn, who gave a terrific speech earlier is sitting right there, so I’m going to speak in just general terms.

I think in all seriousness, on a human level, I think it’s worth addressing the elephant in the room, and that’s me [points to herself with both hands] and the Trump administration. I don’t think anybody—probably most of the people in this room—didn’t support Donald Trump, maybe not at first or maybe ever. And I suspect most of the people in this room didn’t think he’d win. But he has, and the fact that you’re all here—even though you didn’t support this candidate, even though, as you said [pointing to Glasser], people have questions—I think it really speaks to who you are, and the professionalism and the seriousness with which you’ve taken the profession which you’ve all given your lives to—so I want to applaud you, and I particularly want to thank the people I’m on the podium with, because, if the election had turned out differently, everybody would’ve have had a different job. And the fact that you’re here today and not on some desert island somewhere speaks to your character. [Chuckles] So I want to get that out on the table…

What I would like to do—because I’m not going to tell you about the Trump administration policies because that’s what a new administration does; it takes time to rethink things and to come up with its policies. But I will tell you about the mindset and why I, as an untraditional New Yorker, thought Donald Trump was the guy I wanted to support early on. And that’s because I think we’re at a unique moment in American history, and to me, he was the one candidate who would seize that moment. And here’s why I say a unique moment. We have the opportunity—it only happens once every 40 years, more than every generation, every two generations—where the United States has an opportunity to reinvent itself and recreate itself. Now Mike Flynn earlier talked about American exceptionalism as our values and we stand for liberty and freedom and that we are the indispensable nation—we are the one indispensable nation.

But I think there’s another part to American exceptionalism, and that’s that we’re the nation of reinvention. Every one of us in this room probably didn’t start out in the life that you’ve lived. You’ve created yourself out of the opportunities that you’ve had in this country. And that’s what I think has made America truly exceptional. Most countries rise, shine and eventually decline. And America rises, shines, and maybe declines a little bit but rises again in an even better and greater form.

And that’s the moment we’re at because the stars have aligned to make this unique historic movement, and for the following reasons: tax reform. Donald Trump has talked about a pro-growth economy. Tax reform is probably going to liberate—particularly the corporate tax reform—$2 or $3 trillion that will come back to the United States, to be repatriated to invest in infrastructure and new inventions. Secondly, regulatory reform. We saw in the Reagan administration, where I was a foot soldier, that regulatory reform really did encourage the development of small business. The third thing is we have cheap energy—cheap and abundant and secure energy. We have been in this quest as America since the 1970s—where can we find cheap and abundant and secure energy sources. And then finally, we have a dozen disruptive technologies. How many people in this room have an iPhone? [Raises hand for a show of hands] Right, everybody’s got an iPhone except the people at Samsung. We don’t let them in the room [laughs], but, if you’ve got an iPhone, that didn’t exist ten years ago. And yet think of how it’s changed your lives. It’s not just calling somebody; it’s how you access information; it’s how you shop. It’s all aspects of your lives have been changed by the iPhone. Well there are a dozen iPhone-like technologies that have been invented in America; they’re going to be manufactured in America; and they’re going to be sold not only to America, but to the world. And it’s stuff like wearable medical devices; it’s self-driving cars; robotics, nanotechnology, bio-engineering, it’s DNA-designed medicine—all of these things are just waiting to be mass-produced in America, so I look at this and I’m a glass half-empty person. I studied nuclear weapons systems at MIT—you know, you’re not supposed to be thinking about the good news in that field. But I look at this and say we’re in America where the glass is half full because, with a few political decisions—which is why I like Donald Trump because I think he’s the guy to make those decisions—we’re going to have an economic renaissance.

Secondly, it’s not just the economy, stupid, but it’s also American national security, and it’s the rebuilding of America’s defenses. I don’t think a lot of people think—and we can say later who, why, who blame, that blame—but American foreign policy in the last 15 years has not been a happy story. Yet if we have the opportunity now to rebuild our defenses—as Gen. Flynn said, “Peace Through Strength”—when Ronald Reagan chose those words, he did it very deliberately. It wasn’t peace through capitulation or peace through conquest, and it wasn’t economic strength, military strength, diplomatic strength, moral strength—it was all those things together. And I think we have another opportunity to do that again. So when I look at the future and ask what is the mindset and where does America go from here, I think we have a new president who’s going to seize this unique historic moment and he’s going to rebuild America’s defenses. And not only does it make our lives better as Americans, but it gives us leverage and opportunities and options that we’ve not had for over a generation. And that’s not just to rethink American foreign policy—nobody’s talking about giving up the things that have been a part of the American post-war period—but it’s maybe to recalibrate, as Gen. Flynn said, or see what other opportunities exist to strengthen them.

And so the three bedrock principles that we want—you know, what is the Trump foreign policy—I think you can talk about the things that have been tried and true. You know when Steve Hadley and I were junior NSC staffers together, or when you’ve been in government [gestures to Flournoy) or when you’ve been in government (gestures to Sullivan). And it’s things like—you know, it’s America’s values—that’s going to continue to be the bedrock of American foreign policy. It’s American global leadership, it’s going to continue. It may have a different form, and we may have more options and more opportunities to do it. And finally, it’s the alliance structures that have kept the peace for as—did you realize since World War II, this is the greatest and longest period of world-power peace since the fall of the Roman Empire?—75 years that we have not had global wars. And a lot of that is because of our alliances. So I would say, all of you, relax. It’s going to be great. We’re going to make America great again. [Laughs] And welcome along for the ride. Thank you.

Question: Russia and China Policy?

You know, I think one of the biggest problems that we as Americans—and it’s not a partisan thing—the mistake that we make, it’s that we constantly tell other countries how they should think. You know, “it’s in your best interest to do this [pointing to the right], or you know, what you should do is that [pointing to the left].” And you know, American foreign policy has had the luxury of being the most powerful economic, political, diplomatic power certainly in the last several centuries, probably of all time. And the fact that we kind of assume everybody thinks the way we do is to make a fundamental mistake. And it’s not so much what we’re thinking—but how are they thinking, how do they see the world? Maybe they see the world the way you’re [nodding to Hadley] talking about. But maybe we spent way too long trying to tell them what to think.

And, what I’m hoping in this period—which, again, I think is a very transformational period, not just for the United States, but for the world—is that we can start seeing things through their eyes. I mean, our old boss, Henry Kissinger, and he was an expert at this—he was a genius at seeing what did they think, what were their needs, how could we give them their needs but at the same time advance American foreign policy and American national security interests. When I look at the world today—and not how they should think, but the reality, where things are going. You know, China has been an ascendant rising power economically and in other ways, but ascendancy, particularly built on economic growth, is starting to slow down. Russia has had Vladimir Putin. Go look at his graduate dissertation that he wrote in the late 1980s as the Soviet empire was collapsing, and he wrote a graduate thesis that said I’m going to rebuild, Russia can rebuild itself by using its natural resources, bring them under state control, and then when the prices of energy rise, Russia will be in a dominant position. And he’s followed it to the letter, EXCEPT, what he didn’t anticipate was fracking, and he didn’t anticipate the energy revolution so that the price of oil has gone down. What does that mean for him? What does that mean for Russia’s long-term future? At the same time, I look at the Middle East where we have been tethered to the Middle East since the 1970s in the quest for cheap and abundant, secure energy. And yet the Middle East—I don’t think anyone in this room thinks that peace is going to break out any time soon. So all of these things are—the chessboard is moving, the tectonic plates are shifting. And what is America’s opportunity, whether it’s with Xi Jinping or whether it’s with Vladimir Putin or whoever it is in the world, I think it gives us an opportunity. I can’t tell you what those moves are; I can just tell you that the nimbleness with which America can conduct its foreign policy, particularly after a period of economic growth, will give us options and leverage to take advantage of all of those opportunities as they present themselves [Hadley nods sagely throughout this last disquisition].

Question: Reconciling Trump Policy with Kissingerian Realpolitik and Reagan’s Democracy Promotion

I always think of the eagerness that most graduate students take to try to put everybody in this kind of category and catalogue. I just don’t think that; I mean it’s a different world. Things change. What Henry Kissinger was able to do is a different world than what Ronald Reagan was able to do. I mean I look at the post-war period and, say, during the post-war period, we emerged from the post-war period with two adversaries that were existential threats to the United States in the sense of nuclear weapons, and that was the Soviet Union and China, and that was the Sino-Soviet alliance. So what was the Kissingerian foreign policy? Well, he was able to put a wedge between the Sino-Soviet alliance. What did Ronald Reagan do? He was able to take the Soviet Union, which was the remaining existential threat to the United States and turn that around. How did he do it? Not by fighting. You know, this was a war that was won without firing a shot. The one thing I can tell you about Donald Trump is that, if you listen to what he says, when he talks about things like deterrence, he doesn’t use the word deterrence. He didn’t go to grad school where most of you guys went. Um, he’s a businessman. But when he talks about let’s build America’s defenses so we don’t have to use them, that is the essence of deterrence. That is peace through strength. That is not build up your military so you go use it; it’s build your military up so that nobody picks a fight with you. And that was Ronald Reagan philosophy. On the other hand, there are parts of Nixon and Kissinger that I think Donald Trump has also advocated. So I’m not going to be put into the little academic grad school box because I think it doesn’t suit and it doesn’t apply in a rapidly changing world.

Question: How Is World Reacting to Trump and Trump Effect?

Let me answer a little differently because I really don’t want to get into the Trump administration foreign policy. Let me talk about the Trump effect. To me, the greatest threat to American national security in the last, let’s say, 20, 30 years has not come from abroad but has come from within. And that is that the assumption of American democracy is predicated on participation. We’re in it together. Somebody wins, somebody loses. We go home; we decide we’re going to support the other candidate. We come back again and we decide to support somebody different again. And the real problem with the American community is that the last, you know, for decades, 40% of the population just checked out. They may have had opinions, but they never went to the polls; they didn’t vote. You’d ask people, and they’d say, “Well, I’m not political. I’m not gonna go vote. It’s not for me.” And that I think was the greatest threat to the country because, again, a democracy is predicated on participation, and, in 1776, the Constitution, the Declaration of Independence, the Constitution that was written assumed that we would take not just the opportunities of democracy and the privileges, but the responsibility for self-governance. And when I look at the American political landscape, the thing that I think is the Trump effect is, a lot of that 40%, they’re back in the game. Now, you may not like some of the things that they believe in or you might love some of the things that they believe in. But the fact that they’re in the game is something that strengthens democracy because you never want to get to the point where people don’t participate. They don’t feel it’s them. They feel disconnected from the country because we have been given the gift of the responsibility for democracy falls on our shoulders, and some of the population in this country have decided it wasn’t for them. They’re back in the game, and I think if you got that going for you, if the American public feels that they’re back participating, they’ve got a piece of the action, they’ve got skin in the game, then I think there isn’t any problem that’s too big for us to solve, because look at American history. I mean this is tough, I get it. The civil war was tougher. Valley Forge was a lot tougher. The Depression was worse, and when the American people are together, we are not only the indispensable nation, we’re unstoppable because we’re inventive, we’re creative, we’re entrepreneurial—all of those things, and yet we’re never any of those things if 40% of the nation checks out. They’re back in the game, and, as far as I’m concerned, that’s the Trump effect, and that’s the single most important thing that I take away from this election.

Question: Most Underrated and Overrated Accomplishment of Obama Administration.

{When discussion moves to McFarland, she asks to be reminded of the question and then abruptly interrupts Glasser and jumps right in.]

You know, one of the things that struck me—I did not support President Obama when he first ran or the second time he ran. But one of my colleagues at Fox News—which is where I used to work until about a month ago—one of my colleagues was Juan Williams—African American man who’s a very respected journalist and somebody I think very highly of as a human being—and he said the night that Barack Obama was elected—he said, “you don’t understand what this means. You don’t understand what this means to me,” and I thought, “God, I don’t really get this.” And he said, “I’m an African American, and there have been times—a lot of times—when I haven’t felt that I’ve been treated equally or considered equally.” And so he said when Barack Obama won the presidency, it was a change that he felt in a fundamental way.

And I kept thinking back to when Geraldine Ferraro was the first woman to be on a national ticket and when she was vice president [pause] in the Democratic Party to Mondale, I didn’t support her either. But I sure felt great about the fact that a woman was breaking through that glass ceiling. So whatever else you say about you did like his foreign policy [or] you didn’t, you did like Obamacare, you didn’t, I think that just the fact that a man like that, that people a generation before would never have thought an African-American man could win. I don’t think that’s the only thing I want to remember Barack Obama for, but it showed to me the same kind of pride in my nation that I felt when Geraldine Ferraro got the nomination. And then it was the same pride that I felt when Sandra Day O’Connor was nominated to be the first woman on the Supreme Court, a woman I did get to know and consider a friend. But it was that same notion, that stuff you didn’t think was going to happen a generation before has happened. And when I look around today at the kind of people who are assuming national leadership roles, it, again, to rise above the partisanship and all the rest, it makes me really proud that I’m a member of this country where people can rise on their own qualities, and there is just no limit to what they can do if they’re willing to work hard, be a little bit lucky, and follow their dreams. So, I’d like to leave it there.

Question: Advice for Trump about Syria?

Boy, that’s a really tough one. Well, first of all I think I wouldn’t want to say in a public forum what kind of advice I would give to President-elect Trump. But Syria and what it represents in a greater sense [as] a failed state is going to be one of the greatest challenges. You know, throughout history, you worry about countries that get too rich and too powerful and then come to take a piece out of you. In this case, failed states present one of the greatest challenges, and, as you said, Jake, failed states potentially—or as you said, Jake, people who get their hands on weapons of mass destruction, fissile materials—so, the advice I would give is not specifically about that, but about the understanding that failed states (or) weak states which have historically never been a threat to great nations—we are in a new era where failed states, the weakest states in the world community, or even sub-national groups, now can present the greatest threat to world peace and to their neighborhood. Thank you.

Question: Trump’s Failure to Criticize Russia

[Questioner from audience makes reference to just-breaking news about the infamous “dossier” prepared by the British former intelligence agency and what assurances she can make about the incoming administration’s concerns about Russia.]

I don’t know about the story you’re talking about that’s broken and so I don’t think it’s appropriate for me to have any comment about something about which I know nothing. And I know in Washington, people prefer to talk about something about which they know nothing, but I’m going to refrain [and] am not going to take that temptation. I think what Donald Trump has said on a number of occasions is what you just said, Jake, although not in relation to sub-national groups as much as about the Soviet Union—the Soviet Union, now Russia—and its nuclear weapons. I’ve heard him say on a number of occasions, “Nuclear weapons change everything.” So that, I assume, is what is going to carry him on, and when you talk about existential threats to the United States, the existential threat to not only the United States but to people in the world is nuclear weapons in the hands of people who want to use them. Um, throughout the nuclear age, deterrence has kept the peace. We are now in a new era where deterrence may not keep the peace. And I think that, again, I’m going to refrain from jumping right in and giving an opinion about which I don’t know the subject, but thanks.

[Glasser directs a question at Sullivan about what affect the Russian intervention may have had on the election outcome. But McFarland interrupts, preventing a somewhat stunned Sullivan from answering.]

Tell you what, let me say something. You never want to trust a reporter, and I say that as somebody from the media. We talked earlier, Susan, about not wanting to get into Donald Trump’s foreign policy. What I will say, however, is (pause), you know I’m not going to say what Donald Trump thinks about, say, the election and what involvement the Russians had. I would say just what Mr. Clapper said, which is that there is no evidence that whatever the Russians did had any effect on the outcome of the election. And for any political leader who is looking at what you’ve said is a change election and what you’ve said—the American people saying, “Hey, you heard us yet?”—that for anybody who wants to sort of blame the loss of Hillary Clinton or the Democrats or the governorships or the senators or the House of Representatives or the Democratic Party, you’re making a mistake if you think that it’s because of some other thing. It’s the American people talking, and I just think it’s a mistake that the Democrats are making if they continue to try to look for a scapegoat. Sometimes it’s just better to look at what their positions are that have lent [sic] to the dissatisfaction of the country because it’s not just one election. If you look at the past several elections, it’s been governorships that have been lost; it’s been state legislatures that have been lost; it’s been senators that have been lost; it’s been congressional seats that have been lost. And so I’m really not going to jump into the middle of that.

[Glasser asks McFarland for final remarks]

In 1970, I went to the White House for the first time. I was a college freshman, and my poor family from the Midwest—my parents hadn’t gone to college, my grandparents (inaudible)—I had to pay my way through college, I had a part-time job, working in the White House Situation Room. I was the night-shift secretary on Henry Kissinger’s staff, and when I had that job, if you had told me that I was going to live to see a Michele Flournoy in the positions you’ve had [pointing to Flournoy], or a Madeleine Albright or Hillary Clinton or a Condi Rice, I would probably have just said, “Really, you know?” In my era, women, you could get a college degree, and that was terrific. You could probably be an executive assistant, and maybe you could be, you know, a super-secretary. You might even be a research assistant. But I never would have thought that 45 years later—and, by the way, I am probably the oldest person in this room—but, 45 years later, that it would not only be de rigueur, but, you know absolutely nobody bats an eyelash at the thought that a woman could do any of those things. So I look at this [as] I’ve stepped on the shoulders of some great women. Some of them are older than I am, but some of them are [pause], and the idea that America is passing the baton is not that we’re arising out of nothing, and that history began when we walked into the White House. It’s the fact that we’re standing on the shoulders of the people who came before—the women who came before certainly, but everybody who came before. And so the way this new administration is going to take traditional American values, take a traditional American global leadership role, take the traditional alliances that have served so well for 75 years, I do see this is a building upon something, and it is a passing of the baton. And that is one of the great reasons to celebrate this institution, the bipartisan, fractious [laughs] nature of our politics. But I think it’s a great testimony to the experiment that is America and that continues to be the shining city on the hill.

Photo of K.T. McFarland by Gage Skidmore via Flickr.

Jim Lobe has the patience of a saint to prepare this for us! Even looking at the names of the videos (Lindsey Graham, for example) and never having heard of KT McFarland, made me rush to the transcript, and I could not read all of it. To think that people like that are in charge of us, just the day after hearing from and about the monstrous Stephen Miller, sends shivers through the spine.

Now we know where the Veep character Selena Meyer gets her speaking style.