by Andrew Bacevich

Apart from being a police officer, firefighter, or soldier engaged in one of this nation’s endless wars, writing a column for a major American newspaper has got to be one of the toughest and most unforgiving jobs there is. The pay may be decent (at least if your gig is with one of the major papers in New York or Washington), but the pressures to perform on cue are undoubtedly relentless.

Anyone who has ever tried cramming a coherent and ostensibly insightful argument into a mere 750 words knows what I’m talking about. Writing op-eds does not perhaps qualify as high art. Yet, like tying flies or knitting sweaters, it requires no small amount of skill. Performing the trick week in and week out without too obviously recycling the same ideas over and over again — or at least while disguising repetitions and concealing inconsistencies — requires notable gifts.

David Brooks of the New York Times is a gifted columnist. Among contemporary journalists, he is our Walter Lippmann, the closest thing we have to an establishment-approved public intellectual. As was the case with Lippmann, Brooks works hard to suppress the temptation to rant. He shuns raw partisanship. In his frequent radio and television appearances, he speaks in measured tones. Dry humor and ironic references abound. And like Lippmann, when circumstances change, he makes at least a show of adjusting his views accordingly.

For all that, Brooks remains an ideologue. In his columns, and even more so in his weekly appearances on NPR and PBS, he plays the role of the thoughtful, non-screaming conservative, his very presence affirming the ideological balance that, until November 8th of last year, was a prized hallmark of “respectable” journalism. Just as that balance always involved considerable posturing, so, too, with the ostensible conservatism of David Brooks: it’s an act.

Praying at the Altar of American Greatness

In terms of confessional fealty, his true allegiance is not to conservatism as such, but to the Church of America the Redeemer. This is a virtual congregation, albeit one possessing many of the attributes of a more traditional religion. The Church has its own Holy Scripture, authenticated on July 4, 1776, at a gathering of 56 prophets. And it has its own saints, prominent among them the Good Thomas Jefferson, chief author of the sacred text (not the Bad Thomas Jefferson who owned and impregnated slaves); Abraham Lincoln, who freed said slaves and thereby suffered martyrdom (on Good Friday no less); and, of course, the duly canonized figures most credited with saving the world itself from evil: Winston Churchill and Franklin Roosevelt, their status akin to that of saints Peter and Paul in Christianity. The Church of America the Redeemer even has its own Jerusalem, located on the banks of the Potomac, and its own hierarchy, its members situated nearby in High Temples of varying architectural distinction.

This ecumenical enterprise does not prize theological rigor. When it comes to shalts and shalt nots, it tends to be flexible, if not altogether squishy. It demands of the faithful just one thing: a fervent belief in America’s mission to remake the world in its own image. Although in times of crisis Brooks has occasionally gone a bit wobbly, he remains at heart a true believer.

In a March 1997 piece for The Weekly Standard, his then-employer, he summarized his credo. Entitled “A Return to National Greatness,” the essay opened with a glowing tribute to the Library of Congress and, in particular, to the building completed precisely a century earlier to house its many books and artifacts. According to Brooks, the structure itself embodied the aspirations defining America’s enduring purpose. He called particular attention to the dome above the main reading room decorated with a dozen “monumental figures” representing the advance of civilization and culminating in a figure representing America itself. Contemplating the imagery, Brooks rhapsodized:

“The theory of history depicted in this mural gave America impressive historical roots, a spiritual connection to the centuries. And it assigned a specific historic role to America as the latest successor to Jerusalem, Athens, and Rome. In the procession of civilization, certain nations rise up to make extraordinary contributions… At the dawn of the 20th century, America was to take its turn at global supremacy. It was America’s task to take the grandeur of past civilizations, modernize it, and democratize it. This common destiny would unify diverse Americans and give them a great national purpose.”

This February, 20 years later, in a column with an identical title, but this time appearing in the pages of his present employer, the New York Times, Brooks revisited this theme. Again, he began with a paean to the Library of Congress and its spectacular dome with its series of “monumental figures” that placed America “at the vanguard of the great human march of progress.” For Brooks, those 12 allegorical figures convey a profound truth.

“America is the grateful inheritor of other people’s gifts. It has a spiritual connection to all people in all places, but also an exceptional role. America culminates history. It advances a way of life and a democratic model that will provide people everywhere with dignity. The things Americans do are not for themselves only, but for all mankind.”

In 1997, in the midst of the Clinton presidency, Brooks had written that “America’s mission was to advance civilization itself.” In 2017, as Donald Trump gained entry into the Oval Office, he embellished and expanded that mission, describing a nation “assigned by providence to spread democracy and prosperity; to welcome the stranger; to be brother and sister to the whole human race.”

Back in 1997, “a moment of world supremacy unlike any other,” Brooks had worried that his countrymen might not seize the opportunity that was presenting itself. On the cusp of the twenty-first century, he worried that Americans had “discarded their pursuit of national greatness in just about every particular.” The times called for a leader like Theodore Roosevelt, who wielded that classic “big stick” and undertook monster projects like the Panama Canal. Yet Americans were stuck instead with Bill Clinton, a small-bore triangulator. “We no longer look at history as a succession of golden ages,” Brooks lamented. “And, save in the speeches of politicians who usually have no clue what they are talking about,” America was no longer fulfilling its “special role as the vanguard of civilization.”

By early 2017, with Donald Trump in the White House and Steve Bannon whispering in his ear, matters had become worse still. Americans had seemingly abandoned their calling outright. “The Trump and Bannon anschluss has exposed the hollowness of our patriotism,” wrote Brooks, inserting the now-obligatory reference to Nazi Germany. The November 2016 presidential election had “exposed how attenuated our vision of national greatness has become and how easy it was for Trump and Bannon to replace a youthful vision of American greatness with a reactionary, alien one.” That vision now threatens to leave America as “just another nation, hunkered down in a fearful world.”

What exactly happened between 1997 and 2017, you might ask? What occurred during that “moment of world supremacy” to reduce the United States from a nation summoned to redeem humankind to one hunkered down in fear?

Trust Brooks to have at hand a brow-furrowing explanation. The fault, he explains, lies with an “educational system that doesn’t teach civilizational history or real American history but instead a shapeless multiculturalism,” as well as with “an intellectual culture that can’t imagine providence.” Brooks blames “people on the left who are uncomfortable with patriotism and people on the right who are uncomfortable with the federal government that is necessary to lead our project.”

An America that no longer believes in itself — that’s the problem. In effect, Brooks revises Norma Desmond’s famous complaint about the movies, now repurposed to diagnose an ailing nation: it’s the politics that got small.

Nowhere does he consider the possibility that his formula for “national greatness” just might be so much hooey. Between 1997 and 2017, after all, egged on by people like David Brooks, Americans took a stab at “greatness,” with the execrable Donald Trump now numbering among the eventual results.

Invading Greatness

Say what you will about the shortcomings of the American educational system and the country’s intellectual culture, they had far less to do with creating Trump than did popular revulsion prompted by specific policies that Brooks, among others, enthusiastically promoted. Not that he is inclined to tally up the consequences. Only as a sort of postscript to his litany of contemporary American ailments does he refer even in passing to what he calls the “humiliations of Iraq.”

A great phrase, that. Yet much like, say, the “tragedy of Vietnam” or the “crisis of Watergate,” it conceals more than it reveals. Here, in short, is a succinct historical reference that cries out for further explanation. It bursts at the seams with implications demanding to be unpacked, weighed, and scrutinized. Brooks shrugs off Iraq as a minor embarrassment, the equivalent of having shown up at a dinner party wearing the wrong clothes.

Under the circumstances, it’s easy to forget that, back in 2003, he and other members of the Church of America the Redeemer devoutly supported the invasion of Iraq. They welcomed war. They urged it. They did so not because Saddam Hussein was uniquely evil — although he was evil enough — but because they saw in such a war the means for the United States to accomplish its salvific mission. Toppling Saddam and transforming Iraq would provide the mechanism for affirming and renewing America’s “national greatness.”

Anyone daring to disagree with that proposition they denounced as craven or cowardly. Writing at the time, Brooks disparaged those opposing the war as mere “marchers.” They were effete, pretentious, ineffective, and absurd. “These people are always in the streets with their banners and puppets. They march against the IMF and World Bank one day, and against whatever war happens to be going on the next… They just march against.”

Perhaps space constraints did not permit Brooks in his recent column to spell out the “humiliations” that resulted and that even today continue to accumulate. Here in any event is a brief inventory of what that euphemism conceals: thousands of Americans needlessly killed; tens of thousands grievously wounded in body or spirit; trillions of dollars wasted; millions of Iraqis dead, injured, or displaced; this nation’s moral standing compromised by its resort to torture, kidnapping, assassination, and other perversions; a region thrown into chaos and threatened by radical terrorist entities like the Islamic State that U.S. military actions helped foster. And now, if only as an oblique second-order bonus, we have Donald Trump’s elevation to the presidency to boot.

In refusing to reckon with the results of the war he once so ardently endorsed, Brooks is hardly alone. Members of the Church of America the Redeemer, Democrats and Republicans alike, are demonstrably incapable of rendering an honest accounting of what their missionary efforts have yielded.

Brooks belongs, or once did, to the Church’s neoconservative branch. But liberals such as Bill Clinton, along with his secretary of state Madeleine Albright, were congregants in good standing, as were Barack Obama and his secretary of state Hillary Clinton. So, too, are putative conservatives like Senators John McCain, Ted Cruz, and Marco Rubio, all of them subscribing to the belief in the singularity and indispensability of the United States as the chief engine of history, now and forever.

Back in April 2003, confident that the fall of Baghdad had ended the Iraq War, Brooks predicted that “no day will come when the enemies of this endeavor turn around and say, ‘We were wrong. Bush was right.’” Rather than admitting error, he continued, the war’s opponents “will just extend their forebodings into a more distant future.”

Yet it is the war’s proponents who, in the intervening years, have choked on admitting that they were wrong. Or when making such an admission, as did both John Kerry and Hillary Clinton while running for president, they write it off as an aberration, a momentary lapse in judgment of no particular significance, like having guessed wrong on a TV quiz show.

Rather than requiring acts of contrition, the Church of America the Redeemer has long promulgated a doctrine of self-forgiveness, freely available to all adherents all the time. “You think our country’s so innocent?” the nation’s 45th president recently barked at a TV host who had the temerity to ask how he could have kind words for the likes of Russian President Vladimir Putin. Observers professed shock that a sitting president would openly question American innocence.

In fact, Trump’s response and the kerfuffle that ensued both missed the point. No serious person believes that the United States is “innocent.” Worshipers in the Church of America the Redeemer do firmly believe, however, that America’s transgressions, unlike those of other countries, don’t count against it. Once committed, such sins are simply to be set aside and then expunged, a process that allows American politicians and pundits to condemn a “killer” like Putin with a perfectly clear conscience while demanding that Donald Trump do the same.

What the Russian president has done in Crimea, Ukraine, and Syria qualifies as criminal. What American presidents have done in Iraq, Afghanistan, and Libya qualifies as incidental and, above all, beside the point.

Rather than confronting the havoc and bloodshed to which the United States has contributed, those who worship in the Church of America the Redeemer keep their eyes fixed on the far horizon and the work still to be done in aligning the world with American expectations. At least they would, were it not for the arrival at center stage of a manifestly false prophet who, in promising to “make America great again,” inverts all that “national greatness” is meant to signify.

For Brooks and his fellow believers, the call to “greatness” emanates from faraway precincts — in the Middle East, East Asia, and Eastern Europe. For Trump, the key to “greatness” lies in keeping faraway places and the people who live there as faraway as possible. Brooks et al. see a world that needs saving and believe that it’s America’s calling to do just that. In Trump’s view, saving others is not a peculiarly American responsibility. Events beyond our borders matter only to the extent that they affect America’s well-being. Trump worships in the Church of America First, or at least pretends to do so in order to impress his followers.

That Donald Trump inhabits a universe of his own devising, constructed of carefully arranged alt-facts, is no doubt the case. Yet, in truth, much the same can be said of David Brooks and others sharing his view of a country providentially charged to serve as the “successor to Jerusalem, Athens, and Rome.” In fact, this conception of America’s purpose expresses not the intent of providence, which is inherently ambiguous, but their own arrogance and conceit. Out of that conceit comes much mischief. And in the wake of mischief come charlatans like Donald Trump.

Reprinted, with permission, from TomDispatch.

Andrew J. Bacevich, a TomDispatch regular, is the author of America’s War for the Greater Middle East: A Military History, now out in paperback. Follow TomDispatch on Twitter and join us on Facebook. Check out the newest Dispatch Book, John Feffer’s dystopian novel Splinterlands, as well as Nick Turse’s Next Time They’ll Come to Count the Dead, and Tom Engelhardt’s latest book, Shadow Government: Surveillance, Secret Wars, and a Global Security State in a Single-Superpower World. Copyright 2017 Andrew J. Bacevich

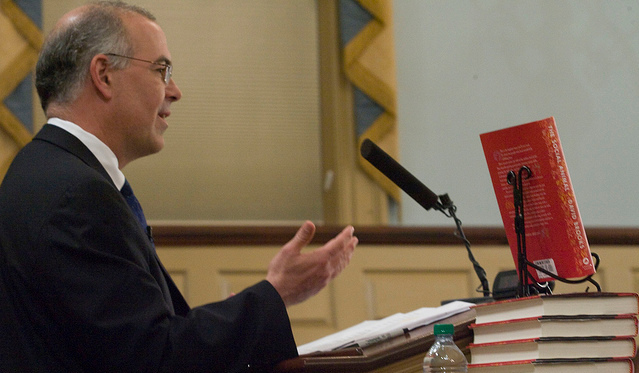

Photo: David Brooks courtesy of Miller Center via Flickr.

Some really wise group of inspired pizza latenight eating young historians need to binge do a project to come up with a grading system like Baseball Card metrics, to measure all leaders, all countries, all human history. It’s a project for the youth, for the world is their future abode. Like have an international meeting of young historians to sort out the world.