by Wayne White

As the violence in Libya grinds on and the two rival governments find little common ground, months of UN efforts to broker talks have been frustrated. Although both are insecure, the competing governments believe they have some advantages that could be lost or degraded by compromise, particularly the challenger in Tripoli. Meanwhile, except for one bright spot, extremists continue to capitalize on the inability of either government to secure the country. Closure between the two is needed, and perhaps targeting Libyan extremists and patching up the oil sector could be used as confidence-building measures to jump start talks.

A series of recent terrorist attacks have hit Western and governmental targets in Tripoli. The city is under the sway of the rump former General National Council (GNC) legislature comprised of Islamist members and backed by the “Libya Dawn” (LD) Islamist militia from Libya’s third largest city, Misrata. A bombing at the Algerian Embassy on Jan. 17 wounded three guards and on Jan. 24 attackers in a car opened fire at Libyan police outside UN offices in Tripoli. In November, the United Arab Emirates (UAE) and Egyptian embassies were bombed. It is unclear who carried out these attacks. All three countries oppose the GNC/LD, but the latter seems to take seriously its responsibility to guard these facilities.

Tripoli’s Corinthia Hotel, where GNC Prime Minister Omar al-Hassi resides along with many foreigners still doing business in Libya, was attacked on Jan. 27. Although Hassi and his entourage were elsewhere, the attackers killed five foreigners and four guards. A Tripoli-based Islamic State (IS) group claimed responsibility, stating the attack was retaliation for the Jan. 2 death of Libyan al-Qaeda operative Abu Anas al-Libi, who was in US custody at the time. On Jan. 12, the same IS affiliate said it had taken 21 Egyptian Coptic Christians hostage in GNC/LD territory and bombed a Tripoli foreign ministry building after a senior Tripoli official’s public “Merry Christmas” message on Dec. 24 (Libyan Independence Day).

In the east, where the majority secular House of Representatives (HOR)—elected last June and recognized by the international community—resides in Tobruk (after losing Tripoli), HOR forces under Qadhafi-era General Khalifa Haftar (or Hiftar) have made considerable progress against extremists in Benghazi. HOR troops reportedly have driven the al-Qaeda associated Ansar al-Sharia in Libya (ASL) militia out of 90% of the city. ASL confirmed the death of its leader Mohamed al-Zahawi on Jan. 25 from battle wounds received last year in Benghazi. Due to Haftar’s success, the HOR formally recalled him to duty along with dozens of other former army officers working with him.

For its part, the rival GNC/LD alliance has consolidated the gains it made driving last month far to the east of Tripoli toward Libya’s biggest oil export terminals of es-Sider and Ras Lanuf. A tribe affiliated with the Tripoli government reportedly now controls the desert oilfields that supply these terminals. Although the HOR still holds the terminals, these moves place LD forces on the doorstep of the HOR’s area of influence. Still, if Haftar finally has the ASL and its extremist allies on the run, he could concentrate more forces against LD in this contested area.

Until recent weeks, the two sides appeared to have allowed the Libyan National Oil Corporation (NOC) and the Central Bank (LCB) to function neutrally. That is over. Both governments have appointed rival NOC and LCB directors as well as their own oil ministers. In the Benghazi fighting, Haftar’s troops secured the large eastern-based branch of the LCB. They apparently did not loot it as the Tripoli government alleged, but HOR Prime Minister Abdullah al-Thinni (or al-Thani) has moved to set up new oil revenue bank accounts out of reach of Tripoli. Meanwhile, nearly half of Libya’s latest oil production of around 350,000 barrels per day must be used domestically, not for export, with the LCB digging ever deeper into the country’s financial reserves to make do.

Oil has also fueled violence at sea. This week, the HOR forced a foreign tanker bound for LD in Misrata to divert to Tobruk or be bombed. Last week, HOR warplanes struck a smaller vessel apparently heading for GNC/LD territory with fuel. Consequently, on Jan. 27 the International Chamber of Shipping warned all commercial vessels “to avoid Libyan waters if possible.”

Getting the UN Off Square One

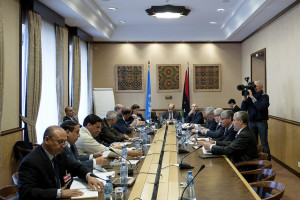

Libyan participants and UNSMIL officials at the UN political dialogue meeting hosted at the Palais des Nations in Geneva on Jan 27. Credit: UN Photo/ ean-Marc Ferré

UN Envoy for Libya Bernardino Leon has tried in earnest since early December to bring the two rival governments together in Geneva, with another attempt beginning this week. He is seeking a national unity government. Consistently, the HOR has sent representatives; the GNC/LD has not, though a minority within the Tripoli government wants to attend. In fact, some LD officials from areas beyond Tripoli—including Misrata—came to Geneva this time around. And Tripoli reportedly has indicated it too would participate if talks were held in Libya. Thinni seems agreeable, but only if the site is in the HOR-controlled east—a tough sell for Tripoli.

Both governments are profoundly insecure. The Libyan Supreme Court (sitting in GNC/LD-ruled Tripoli) declared last November that the electoral and constitutional underpinnings of the HOR’s election last June were flawed. Also, the HOR is painfully aware that because of widespread instability, only 18% of registered voters participated. For their part, the GNC/LD combo feels threatened because the GNC’s own mandate expired early last year, and the present GNC is only a portion of the original body.

At the same time, both governments have advantages they are reluctant to surrender in negotiations. Haftar’s recent gains aside, the GNC/LD still enjoys greater military success, especially in running the HOR out of Tripoli. The HOR, however, possesses international legitimacy with the court decision against it regarded suspiciously and the HOR’s moderation greatly preferred.

Since the GNC and LD have roundly denounced Islamic extremists like the ASL as “terrorists” and purport to represent a more moderate Islamist tendency, cooperation between Tripoli and Tobruk to suppress dangerous militants could create some common ground. With the recent binge of IS-driven activity affecting Tripoli most directly, such an approach might appeal to the GNC/LD. Exchanging information on “terrorist” activity also could help both governments take on their respective militant foes.

There is not enough trust for joint operations, but each could commit to do all possible to snuff out al-Qaeda, Islamic State affiliates, and their extremist allies in or near their respective holdings. This would include such groups in the Fezzan south of Tripoli and al-Qaeda in the Islamic Maghreb (AQAP) along with other extremists in safe havens in Libya’s southwest corner (all closer to the GNC/LD in Tripoli). The HOR would have to finish cleaning up Benghazi and smash the Islamic State affiliate holding much of nearby Derna.

Egypt and the UAE, which back the HOR, would be opposed to HOR concessions to Islamist Tripoli in the talks. If, however, the GNC/LD demonstrated its bona fides as a truly moderate Islamic entity, that opposition might soften. Likewise, the HOR could become more willing to consider a less exclusionary relationship with Tripoli.

Both governments also would benefit from a joint effort to restore the bulk of Libya’s oil exports and domestic refining. Each holds key pieces of that puzzle. Before doing so, however, both must agree on a common instrument for interfacing with buyers and holding revenue. Anti-extremism (if Tripoli’s assurances are credible) and oil would give the two sides plenty to talk about in whatever venue.

Among the caveats that beg mention regarding such a diplomatic approach is the fact that Libyan instability is far from just a two-dimensional problem. Beneath the Tripoli-Tobruk brawl lies a maze of crosscutting regional, local, tribal and militia conflicts that can hardly be worked out at UN-brokered talks between the two leading players. Nonetheless, the difficult road back toward greater stability must begin somewhere.

Any revolution that removes a strong leader without having a replacement is bound to fall into a chaos until one individual leading a strong and organized group emerges.

In Egypt we saw successively Morsi and the Moslem Brotherhood than Al Sissi and the army. That prevented the chaos but has not brought the ‘ideals’ of the revolution.

In Tunisia Marsouki and the Al Nahda party lead the revolution. Yet the group that replaced it has yet to prove it can prevent the chaos to blow back sooner or later.

Yemen, and Libya have been left headless with the killing and the forced resignation of the president without anyone leading a strong group to prevent chaos. The Houthis are emerging now as the potential force to lead the country and it is hoped it will work out.

Syria has kept its leader backed by its army and therefore has allowed a central control of the country, despite the loss in lives and territory.

Libya is the worst of all, despite the huge military help the revolution got from the West. It is a chaos and the West bears a huge responsibility to have provoked it and let it rot.

Stabilizing Libya is so hard because of the interventionist attitudes of all the foreign meddlers, including other Middle Eastern countries, the West, and the Jihadis. It has become very acceptable and even respectable to pull these interventionist stunts and blame other players who do the same.

So far this first part of the 21st century, the West with the most, have been producing failure after failure because it doesn’t know what it’s doing. It doesn’t matter how many idiots it takes to screw in the light bulb, because the idiots don’t know what a light bulb looks like today. I just hope that someone doesn’t proclaim all these were done in the name of vital interests of the Governments involved in destroying the various leaders for regime change. All the western governments don’t seem to know their backside from a hole in the ground, nor do they give a whiff. And let’s forget just who is backing which group in the overthrows. Of course, this is all IMHO, but then there shouldn’t be any complaining when it comes back to bite them in the ass because it didn’t turn out the way the idiots predicted.

Stabilize Libya? More like the goal was to destabilize Libya, along with God knows how many other places around the world. The Empire of Chaos strikes again.

While libya can be united by a new dictatorship no one is willing or capable of taking on that task given the new reality in the Mid-East.The cry for freedom and democracy may be lost in the chaos of today but that sentiment is stronger than it ever was in the history of Islam and it will return libya to it’s original roots of three nations hence the term Tripoli. A federal system reflecting the divisions of this nation is the most likely path to success for Libya and the Arab League and UN should persue that path