by Thomas Lippman

For once the news from the Middle East doesn’t seem to be all bad. That doesn’t mean the news is good—most of it is not—but amid all the continuing conflicts some encouraging signs of sanity and seriousness of purpose have appeared.

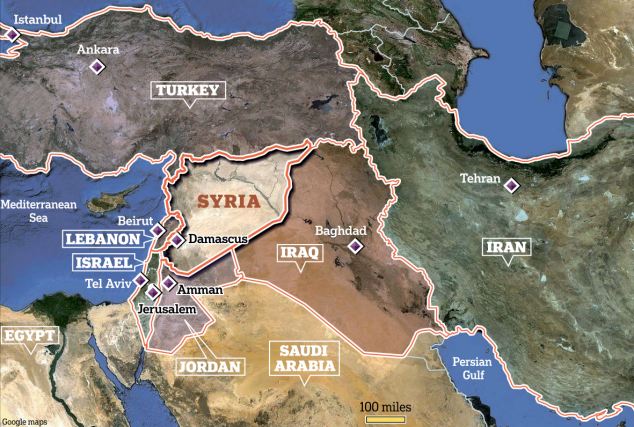

On the surface, there is little reason to be upbeat. The wars in Syria and Yemen continue unabated. No political settlement is in sight for Libya. The Islamic State is still in control of most of the territory it seized last year in Syria and Iraq, and is still threatening its neighbors. Egypt is battling a violent insurgency in the Sinai. Mosque bombings have killed dozens in Saudi Arabia. And a truce in the old conflict between the Turkish government and the Kurdish separatist group known as the PKK has once again dissolved into gunfire. Across the region, millions of destitute refugees still need food and shelter.

But even so, several seemingly unrelated events in the past couple of weeks could raise hopes for better times.

To begin with, the six Arab monarchies of the Gulf Cooperation Council, including Saudi Arabia, have put aside whatever reservations they may have about the international nuclear agreement with Iran and have accepted it, in order to bolster their security and military partnerships with the United States. Qatar, which seventeen months ago was in such disfavor that three of the other countries withdrew their ambassadors, is back in the fold and was the host this week of a GCC foreign ministers’ meeting with Secretary of State John F. Kerry.

Qatar’s foreign minister, Khaled al-Attiyah, spoke for the group after the meeting, declaring that the Iran deal “was the best option amongst other options in order to try to come up with a solution for the nuclear weapons of Iran though dialogue, and this came up as a result of the efforts exerted by the United States of America and its allies. We are sure that all the efforts that have been exerted make this region very secure, very stable.”

That the GCC states would accept the agreement had been pretty much a foregone conclusion since their leaders met with President Obama at Camp David in May. Now that they have done so, they say they are prepared to work vigorously with each other and with the United States to combat Iranian troublemaking on other fronts and to beef up their defense capabilities.

Also at Doha was Russian Foreign Minister Sergei Lavrov, who met with Kerry and with Saudi Foreign Minister Adel al-Jubeir to discuss Syria.

A few days later Lavrov announced that Russia, a strong supporter of Syrian President Bashar al-Assad, had invited a major Syrian opposition group to Moscow, in an apparent prelude to a new diplomatic initiative to end that country’s civil war. According to a report in the online news magazine al-Monitor, the group, known as the Syrian National Coalition, has accepted the invitation, though no date for the trip has been announced.

Russia and Iran have been Assad’s principal backers throughout the four-year conflict. Saudi Arabia has committed itself to Assad’s ouster. If Russia is re-thinking its position amid reports that Assad’s position on the battlefield is weakening, it could be a major blow to Iran and its Lebanese proxy, Hezbollah—which has been doing much of the fighting on the , government’s side—and could signal a potential breakthrough in the diplomatic stalemate. In another sign of possible movement, Syrian Foreign Minister Walid Muallem met with officials in Oman, a GCC country that has good relations with Iran. The two countries agreed “that now is the time to unite the efforts to end” the Syria conflict, according to Syrian state media. Muallem met with Iranian and Russian officials in Tehran earlier this week.

A few days after Muallem went to Oman, President Obama said that Russian President Vladimir Putin Vladimir Putin called him last month to explore the possibility of new diplomacy, particularly regarding Syria, which would account for Lavrov’s initiatives.

“I do think the window has opened a crack for us to get a political resolution in Syria,” Obama told journalists at the White House. “Partly because both Russia and Iran, I think, recognize that the trend lines are not good for Assad. Neither of those patrons are particularly sentimental. They don’t seem concerned about the humanitarian disaster that’s been wrought by Assad and this conflict over the last several years. But they are concerned about the potential collapse of the Syrian state. And that means, I think, the prospect of more serious discussions than we’ve had in the past.”

The president stressed the difficulty of devising a solution that would be accepted by all factions in Syria and establishing a representative government. But, he added, “I think the conversations are more serious now than they might have been earlier.”

Then, Russia announced that Saudi Foreign Minister Adel al-Jubeir will visit Moscow next week to talk about Syria.

At the same time, Iranian President Hassan Rouhani appeared to double down on his country’s commitment to Assad. “The Islamic Republic of Iran aims to strengthen its relations with Syria and will stand by it in facing all challenges,” he said after meeting with Syria’s prime minister, Wael al-Halqi, according to Agence France-Presse. But he has also said recently that in both Syria and Yemen, the only way to end the conflict is through political solutions.

Also in the past few days, the United States, Saudi Arabia, and their allies in the war against the Islamic state got a substantial boost from Turkey, which finally entered the war on their side. Turkey, Syria’s neighbor to the north, allowed American warplanes to begin using the air base at Incirlik for missions against the Islamic State, and Foreign Minister Mevlut Cavusoglu said after a meeting with Kerry that his country was ready to do more.

“The US planes have begun arriving and soon we will launch a comprehensive fight against Daesh all together,” he said, using the Arabic acronym for the Islamic State. The fight against the Islamic State has posed a conundrum for Turkey because the most effective forces confronting the extremist group on the ground have been Kurdish units known as Pesh Merga. Ankara fears that strengthening them will strengthen separatist sentiments among the Kurds.

In Yemen, the region’s poorest country even before it was battered by a Saudi-led bombing campaign against rebels known as Houthis that began in March, there were signs that the bombing may be turning the tide.

Ground troops trained by Saudi Arabia and the United Arab Emirates retook the major seaport of Aden from the Houthis. These forces, seeking to restore the ousted government of Abd Rabbo Mansour Hadi, then retook a major air base at al-Anad, north of Aden. They are a long way from retaking the capital, Sanaa, but these reported gains are the first of any significance since the air campaign began.

Saudi Arabia and its partners say the Houthis, who are Shiites like the Iranians but of a different sect, are armed and trained by Iran, although it has never been clear exactly how much support Iran has provided.

According to news reports from the region, Houthi leaders said a political settlement with the exiled government was still possible after what one of them called a “short term” setback in Aden. Saudi Arabia’s position is that any settlement must result in the restoration to power of the “legitimate government,” headed by Hadi. Such an outcome would be seen in the region as a major victory for Riyadh in its rivalry with Iran.

Individually or in the aggregate, these developments don’t mean that the guns will fall silent any time soon. But they do indicate that the region’s major players have understood that the time has come to try some new approaches to the conflicts that threaten to inflame the entire Middle East.

The deal was made because the US realises that it must counter Russian and Chinese in some way and one of those ways includes bringing the Iranians on their side, so to speak and by doing that, they are able to have some control over oil there, which also has the added benefit of keeping the Europeans on a leash and fueling military contracts, particularly to GCC countries.

Naive readers will think of the deal as a win for the liberals which = good; and republican party in general and opposition to deal = bad (even though the republicans and Israel help the U.S. get more concessions from the U.S.).

The countries of the world know it’;s all about global hegemony. But the American audience is fed something else for domestic consumption. They have to be reminded they are noble and superior people, chosen by god to lead the world.