by Paul R. Pillar

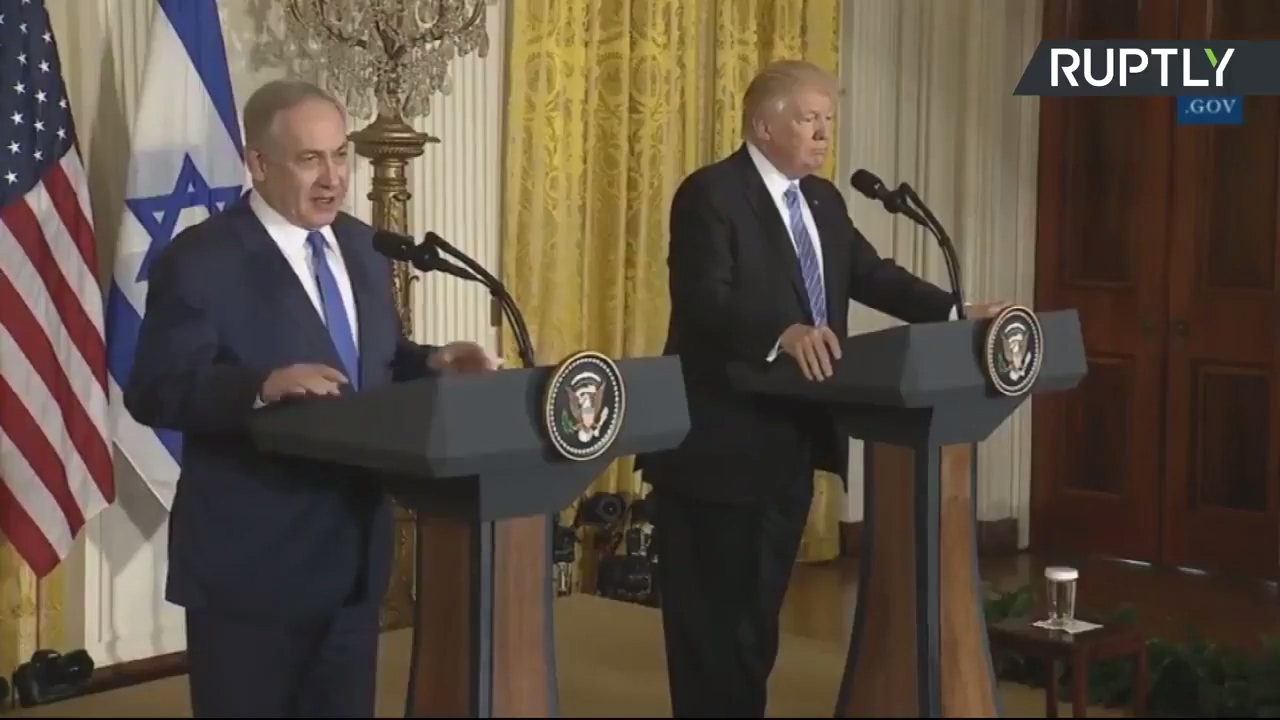

Donald Trump had already moved a long way backward since uttering a few remarks last year raising hopes that he would break out of the straitjacket that binds American politicians on all things involving Israel and the Palestinians and that he would try to be an impartial peace-maker. He later made his peace with Sheldon Adelson, adopted AIPAC’s talking points as his own, and appointed to be U.S. ambassador to Israel a bankruptcy lawyer who is directly involved with West Bank settlements, is politically somewhere to the right of Benjamin Netanyahu, and likens American Jews who do not agree with him to Nazi collaborators. Then this week, in a joint press conference with Netanyahu, Trump appeared to abandon what had been U.S. policy through several administrations, Republican and Democratic, of support for creation of a Palestinian state alongside Israel as the only feasible and durable solution to the Israeli-Palestinian conflict. The president’s exact words were, “I’m looking at two-state and one-state, and I like the one that both parties like. I’m very happy with the one that both parties like. I can live with either one.”

As has become typical with so much of the policy of this month-old administration, confusion reigns. The next day, Trump’s ambassador to the United Nations, Nikki Haley, told reporters, “We absolutely support a two-state solution.” Probably the best interpretation of what was going on at that White House press conference is consistent with insights offered by former U.S. ambassadors to Israel Daniel Kurtzer and Daniel Shapiro, both of whom describe the joint appearance in terms of two leaders dealing with domestic pressures and wanting to look chummy with each other, rather than as an occasion for announcing new diplomatic departures. Specifically, Trump’s comments were a favor to Netanyahu in dealing with the extreme right-wing of his own governing coalition, by pouring some cold water on the two-state concept without Netanyahu having to utter the words “two-state solution” himself.

As random and disorganized as Trump’s tweets, blurts to reporters, or other verbal expressions may be, when the president of the United States says something it either is policy, at least declaratory policy, or affects policy. And so it must be noted how utterly unreal, and divorced from the concept of a true peace agreement, was Trump’s responding to a question about backing off from commitment to a two-state solution by talking about what “both parties like,” as if there were anything that both parties like right now that would not be a two-state solution. The only thing that the vast majority of Palestinians would “like” is getting their own state or, failing that, full and equal rights for Jews and Arabs alike in a single state. But that latter alternative would be disliked by most Israelis (not just the extreme right) insofar as it would imply, for demographic reasons, destruction of the concept of Israel as a Jewish state.

Trump tosses these words around amid apparent thinking within his own administration and Netanyahu’s about an “outside-in” approach in which development of relations between Israel and some Arab states would lead to Arab pressures on the Palestinians to settle their own conflict with Israel. This notion is far removed from any realistic peace, and not only because the key to ending an occupation is not to pressure the occupied party, who does not control the situation on the ground, rather than the occupier, who does control it. The notion also is merely a derivative of right-wing hopes in Israel, based on finding some common cause with some Gulf Arabs in disliking Iran, that the international opprobrium and isolation of Israel that results from its occupation and apartheid policies can be kept indefinitely at tolerable levels. That is a strategy for indefinitely continuing the occupation and apartheid, not for ending that arrangement and achieving peace.

The Arab states have had their position on the table for fifteen years in the form of the Arab peace initiative, which lays out in simple form the basic trade of full recognition of, and peace with, Israel in return for an end to the occupation and just settlement of the Palestinian refugee problem. The Arab peace plan was modified later to make clear that it includes the possibility of land swaps that would not require all of the West Bank to be returned to Arab sovereignty. There is no reason to expect Saudi Arabia or any of the other Arab governments involved to abandon the concept enshrined in this initiative. And however much one talks about the Arabs’ distractions with their own intramural problems, the sentiments among Arab populations as well as regimes regarding the plight of their co-ethnic brethren in Palestine is not about to be flushed down the toilet by pressuring Palestinian leaders to accept some bantustan-like arrangement and calling it a peace settlement.

As with other early moves of President Trump, his posture on this set of issues illustrates a more general tendency of his regarding governing. Trump billed himself as a master deal-maker, but supporters who liked him for that reason should have looked more carefully at the sorts of deals he was accustomed to making. Most of his business deals were more like one-night stands than like lasting relationships. Sell naming rights, pocket the cash, and let someone else worry about running the enterprise that bears the Trump name. Even when Trump’s own organization was more directly involved in a property, there was a tendency toward cutting and running. His business record featured repeated stiffing of suppliers and sub-contractors and, when necessary, repeated bankruptcies—help on which evidently is part of what earned the settlement-loving David Friedman that ambassadorial appointment.

Note how often Trump’s foreign policy is referred to, by himself and now by others, in terms of whether “a deal” will be made with some other country, whether it is Russia, China, or some other state. Foreign relations should not be thought of in such a one-shot, pointillist way. Foreign relations, and how they affect U.S. interests, are instead a matter of continuing relationships in which interests are always intermingling, colliding, and evolving. “One and done” may work for aspiring pro basketball players, but not for U.S. foreign policy.

This is as true of the Israeli-Palestinian conflict as of other sticky foreign policy problems. Pressuring Palestinians into something that can be labeled a “deal” but does not respond to ordinary human aspirations for a better life and national self-determination does not make a problem go away. It can make it even worse. It can come back in the form of intifadas, terrorism, or something else that damages the interests of Israelis and Americans as well as Palestinians. Trump may not have to worry about such things any more after either impeachment or re-election defeat, but the rest of us will.

This article was first published by the National Interest and was reprinted here with permission. Copyright The National Interest.

@Jeffrey

Clicking on your name at the top of your posts leads directly to your Facebook page, where you post the most appalling racist trash I’ve seen in a long time. I rest my case.

John O, sorry but there is no way you saw any racist trash on my Facebook profile page. So you are a liar. Also, a coward who does not even post your name or any link.

@ Jeffrey Wilens: “… the First Amendment limits Congress and has nothing to do with the USA as a country supporting Israel …”

Jeffrey, you assault your own credibility by making legal assertions without doing the research required to support those assertions.

“More fundamentally, no clear division can be drawn in this context between actions of the Legislative Branch and those of the Executive Branch. To be sure, the First Amendment is phrased as a restriction on Congress’ legislative authority; this is only natural since the Constitution assigns the authority to legislate and appropriate only to the Congress. But it is difficult to conceive of an expenditure for which the last governmental actor, either implementing directly the legislative will, or acting within the scope of legislatively delegated authority, is not an Executive Branch official. The First Amendment binds the Government as a whole, regardless of which branch is at work in a particular instance.”

Valley Forge Christian College v. Americans United for Separation of Church and State, Inc., 454 US 464, 512 (1982) (Establishment Clause case). See also Board of Ed. of Kiryas Joel Village School Dist. v. Grumet, 512 US 687 (1994) (Establishment Clause applies to states as well via the 14th Amendment).

Sorry retired attorney Paul, but those cases have nothing to do with foreign policy. Persons in other countries do not have constitutional rights in the United States. The President does not discriminate against the free exercise of religion by barrings residents of certain Islamic Jihadi states. The constitution is not a suicide pact.

@ Jeffrey Wilen:

@ “The President does not discriminate against the free exercise of religion by barrings residents of certain Islamic Jihadi states.”

You might take that up with the Ninth Circuit, which very recently disagreed with you. I note that the Executive did not apply to the Supreme Court for a writ overruling that Circuit and is instead attempting to draft a new Executive Order that conforms with the Constitution.

@ “… those cases have nothing to do with foreign policy.”

As I noted in my first post, there is nothing in the Establishment Clause’s plain text even hinting that the Clause has no application outside the U.S. borders and I could find no case suggesting that it is so limited. But on the other hand, as was said in Reid v. Covert, 354 US 1, 9-10 (1957):

“This Court and other federal courts have held or asserted that various constitutional limitations apply to the Government when it acts outside the continental United States.” Citing as examples “Balzac v. Porto Rico, 258 U. S. 298, 312-313 (Due Process of Law); Downes v. Bidwell, 182 U. S. 244, 277 (First Amendment, Prohibition against Ex Post Facto Laws or Bills of Attainder); Mitchell v. Harmony, 13 How. 115, 134 (Just Compensation Clause of the Fifth Amendment); Best v. United States, 184 F. 2d 131, 138 (Fourth Amendment); Eisentrager v. Forrestal, 84 U. S. App. D. C. 396, 174 F. 2d 961 (Right to Habeas Corpus), rev’d on other grounds sub nom. Johnson v. Eisentrager, 339 U. S. 763; Turney v. United States, 126 Ct. Cl. 202, 115 F. Supp. 457, 464 (Just Compensation Clause of the Fifth Amendment).”

If the First Amendment prohibition against Ex Post Facto Laws or Bills of Attainder applies extra-territorially, Downes, supra, how then might one argue that the First Amendment’s prohibition against “law respecting an Establishment of Religion” have lesser scope? As was said by the Court in Downes, 182 U.S. at 278:

“Thus, when the Constitution declares that “no bill of attainder or ex post facto law shall be passed,” and that “no title of nobility shall be granted by the United States,” it goes to the competency of Congress to pass a bill of that description. *Perhaps, the same remark may apply to the First Amendment, that “Congress shall make no law respecting an establishment of religion, or prohibiting the free exercise thereof; or abridging the freedom of speech, or of the press; or the right of the people to peacefully assemble, and to petition the government for a redress of grievances.”* We do not wish, however, to be understood as expressing an opinion how far the bill of rights contained in the first eight amendments is of general and how far of local application.”

So we have the Court at least hinting that the Establishment Clause does have extra-territorial scope. Certainly, if Congress enacted legislation that funded the foreign missionary work of a solitary church, would not other churches have a legitimate gripe under the Establishment Clause? The same principle applies to Congress funding the maintenance of a Jewish State.

The ball is in your court, Jeffrey. I have cited my authorities. If you have none supporting your position, then why continue this discussion? Might it be that there are none? As a lawyer, you have the skills to do legal research.