by Robert E. Hunter

The current imbroglio in the Middle East seems to defy both belief and any reasonable approach to make things better, at least from the perspective of those who stand to gain from less rather than more conflict. That includes the United States and most of its friends and allies in the world. But it’s not necessarily true for all of America’s friends and allies in the Middle East. Some of them, less committed than we are to preventing or at least tamping down conflict, are those with which the United States is most closely engaged. That is a major part of the problem and makes more difficult the search for solutions that will enhance US interests.

But one thing that has to be part of the solution rather than the part of the problem is clarity of analysis. To begin with, the US has classical interests in the region, subscribed to for decades by all US administrations. They center on guaranteeing Israel’s security, protecting the flow of oil (at reasonably predictable prices), preventing the export of conflict or terrorism beyond the region’s boundaries (at least not to the United States), keeping the Middle East relatively safe for Westerners to visit and do business, and, if possible, stabilizing key parts of the region to facilitate the pursuit of the preceding interests.

Although internal developments in regional countries, including economic, social, and political progress, are part of the US “values wish-list,” at heart they are only important to the United States to the extent that they help promote more basic Western interests. Notably, so far the so-called Arab Spring, which many observers heralded as a move toward democracy and modernization, has woefully failed to live up to expectations. In some countries, quite the reverse has taken place.

The Limits of Commentary

The effort to provide clarity of analysis regularly spawns a cottage industry of commentators in the media, in the blogosphere as much as anywhere else. Much of this commentary draws on the wealth of knowledge and experience in the United States (and abroad), not just on the Middle East region but also on the ways and means of fashioning responses to events and challenges that the US government could usefully pursue. In the mix of commentary about recent events, from one end of the region to the other, can be found not just nuggets of insight but also a raft of coherent analyses and proposals for doing something useful in regard to current Middle East problems.

All of us can gain from the vigorous, public debate that engages a wide range of perspectives and contending approaches. But it is important to start by understanding one cardinal point: we commentators are outsiders, in the sense that we do not serve in the US government. You have to be in the government in order to have an impact, except, and this very occasionally, at the margins. This can be unfortunate, especially when there is quality thinking that could usefully be incorporated into an administration’s policies and approaches, but it is a long-standing fact of life in Washington.

The issue then becomes whether those people who do serve in the US government, beginning with the president at the top and spreading downward through the bureaucracy, have the capacity for strategic analysis and formulation of policy responses that can adequately address threats, challenges, and opportunities within a basic strategy that makes sense.

As a rule, people serving in senior government positions tend to see the decisions they make in Panglossian terms as the “best of all possible” decisions. This point is regularly made by government spokespeople and other defenders, and by Republican and Democratic administrations alike. Thus those who took the United States into the 2003 invasion of Iraq, which (in this writer’s estimation) was one of the most addle-brained US actions in modern times, still defend what they did. The same is true of people who have served in the Obama administration, despite the burgeoning of conflicts in Syria and Yemen, Iraq’s continuing fragmentation, the risk of war between Iran and Saudi Arabia, assaults by the so-called Islamic State (ISIS or IS), and Wahhabi-inspired terrorism.

Given that things have not gone all that well in major parts of the region under the last two administrations, perhaps outsiders, not needing to justify whatever government is doing, can bring to bear a better perspective on the Middle East and what the US should do about it. That conclusion does not necessarily follow. Maybe our leaders have done the best that can be done. Maybe their greater access to some forms of intelligence information does give them an edge, as does the discipline imposed by the requirement to face each day’s dilemmas, in all their complexity, with no luxury of extended reflection or benefit of hindsight.

One thing is clear, however: outsiders cannot make useful judgment calls about tactics. That includes all of us who think we are experts. It also includes all of the Republican and Democratic presidential candidates. Indeed, one of the truly useless things we have to endure in this campaign season is candidates who pretend that they are commander-in-chief, making the “tough calls,” flexing (verbal) muscles, lecturing the sitting president on what he should do now, and assuring the American people that, should they come to sit in the Oval Office, they would do a better job. This is nonsense, almost by definition. Foreign policy prescriptions in the campaign and especially about tactics (“Here is how I would deal with Syria”) have no instrumental value, either regarding today’s problems or indicating what the candidate would really do if elected. That is unknowable, including to him or her!

The Administration’s Achievements…

Let me make some further stipulations. Most important is that President Obama, supported on a daily basis by Secretary of State John Kerry, successfully negotiated the Joint Comprehensive Plan of Action (JCPOA) with Iran in the face of intense partisan political opposition, much of it promoted from abroad. The JCPOA has effectively ruled out Iran’s acquisition of a nuclear weapon at least for the foreseeable future. Of course, that statement begs the question of whether Iran was intending to get the bomb. It also ignores continuing efforts by the JCPOA’s opponents—notably the Israeli government and some of its more politically active supporters in the United States, along with some of the Sunni Arab states, led by Saudi Arabia—to undercut the nuclear agreement, or at least limit its scope. These efforts may yet be successful. In both cases, there is stout resistance to Iran’s reentry into the outside world, where it could compete with the geopolitical aspirations of other regional countries, including Turkey.

Despite what critics may say, however, President Obama’s achievement regarding the Iranian nuclear program is of major geopolitical significance and ranks among the most significant US foreign policy successes in recent decades.

Further, despite all the media hype about Islamist terrorism being exported to the West, including the United States (e.g., San Bernardino), in fact there has been very little of it and certainly none that has had an impact on the security or survival of any of the targeted countries outside of a tiny fraction of their peoples. Indeed, but for the inflation of this terrorism by the media, especially in the United States, the US president would have earned compliments for acting to reduce the capacity of the Islamist terrorists to do major damage beyond the Middle East. (Obama’s claims on this point, for which he is often ridiculed, are accurate.) The intensive US use of drones and targeted killings, whatever the moral issues involved (e.g., civilian casualties), have largely worked. Both the United States and Europe, along with many Middle Easterners, are safer as a result.

…But Failings of Leadership

Unfortunately, at the same time the administration has not presented convincing evidence of a coherent approach on two other critical fronts. The first relates to what former Secretary of State Madeleine Albright called America’s role as the “indispensable nation.” Critics argue that this vision would have the United States engaged everywhere, potentially getting into trouble here and there, and maybe even causing mischief without intending to do so. But the vision also has a reality: there is still no other country or collection of countries that has the means, perspective, temperament, domestic political support, and history of engagement to do what the United States can do when it puts its mind to it and thinks things through carefully and clearly.

Regrettably, whether in the Middle East or in some other parts of the world, notably in Europe, there is dwindling confidence that the United States is prepared to exercise leadership over the long haul—both as required in particular circumstances and as an end in itself—as the leader of both first and last resort. Indeed, so many of the events in the Middle East in recent months, underscored by Saudi Arabia’s actions this past week, Iran’s reaction, and the further response of Sunni states, reflect in major part the lack of resolve by a major power to play a leading role and to make that clear and consistent to all and sundry. This does not mean that the US can always know what’s best to do or, as a Western nation, can be inherently acceptable, politically or culturally, throughout the Middle East.

But the Obama administration has still not outlined an approach to dealing with IS that, at the very least, appears convincing and inspires confidence. It continues to adhere to the idea that Syrian President Bashar al-Assad must go, and it has convened a negotiating process that includes most of the relevant parties. But it has still not laid out a potential future for Syria and its neighborhood that does not presage more rather than less conflict. In short, “there is no there there” in the administration’s post-Assad game plan.

In the process, the administration has not shown awareness of the need to focus either on the expanding Sunni-Shia civil war or on the competitions that involve Iran and other contenders for regional power. To violate my own stricture against outsiders making tactical suggestions, it is hard to comprehend what kept the United States from making absolutely clear to Saudi Arabia that executing the Shia cleric, Nimr al-Nimr, would be unacceptable to us. It is equally hard to comprehend why the United States has not told Israel that any further settlement construction in the West Bank is unacceptable. Each time the United States appears weak, feckless, or worse, we lose something intangible, and those who depend on us—or who oppose us—take careful notes.

As with any other great power, when friends and allies look to the United States for support, they need to be made aware that there is a price to be paid for ignoring US requirements.

Strategic Vision Missing

At the same time, the administration has not advanced any ideas for a possible security structure for the Persian Gulf region that is not based simply on accepting the Sunnis’ definition of threat from Iran, wrongly defined almost exclusively in military terms. Just opening the arms spigot to Saudi Arabia and other Persian Gulf Arab states misses the point. In fact, the struggle in the region will be more about the modernization of societies rather than military action, where Saudi Arabia, in particular, has hardly made a start. Ideas do exist for the overall, long-term security requirements and possibilities for the region, led by the United States, but they have no traction in the administration.

This critique of the administration’s reluctance to lead and to demonstrate staying power—a matter of orientation as much as of specific policies—raises another key failure: the lack of any overarching strategy for the region as a whole. The United States has been dealing with different parts of the Middle East separately when it should be addressing the region as a whole. The Obama administration needs to engage in strategic thinking, not just problem-solving, which is the forte of lawyers. Such strategic thinking is in stunningly short supply.

But almost none of the Americans most capable of performing these roles for President Obama—experts, seasoned academics, former senior government officials with proven track records on the Middle East—are in the government. This has been true throughout the administration’s life.

Many men have come to the presidency without a strong background in foreign policy. The test is whether he (or in the future she) will have a steep learning curve and make needed adjustments. Ronald Reagan was poorly served by his first four national security advisors, but then he hired two good ones. George W. Bush was in effect mugged by his vice president and others who wanted to pursue their own agenda in the Middle East, and they did so to the nation’s and the world’s cost. But Bush learned from experience, marginalized those who had failed him and the country, and became a far more effective president in his second term.

It is not clear that President Obama has learned that lesson when it comes to strategic thinking and the Middle East. It is almost too late for him to do so by bringing onto his senior Middle East team those Americans who are up to the job of advancing America’s interests in the region in an intelligent, integrated, strategically compelling, and effective way. If he does not, we will have to hope both that circumstances in the Middle East do not become even worse in the next year and that whoever occupies the Oval Office beginning in January 2017 will get things right early in his or her administration.

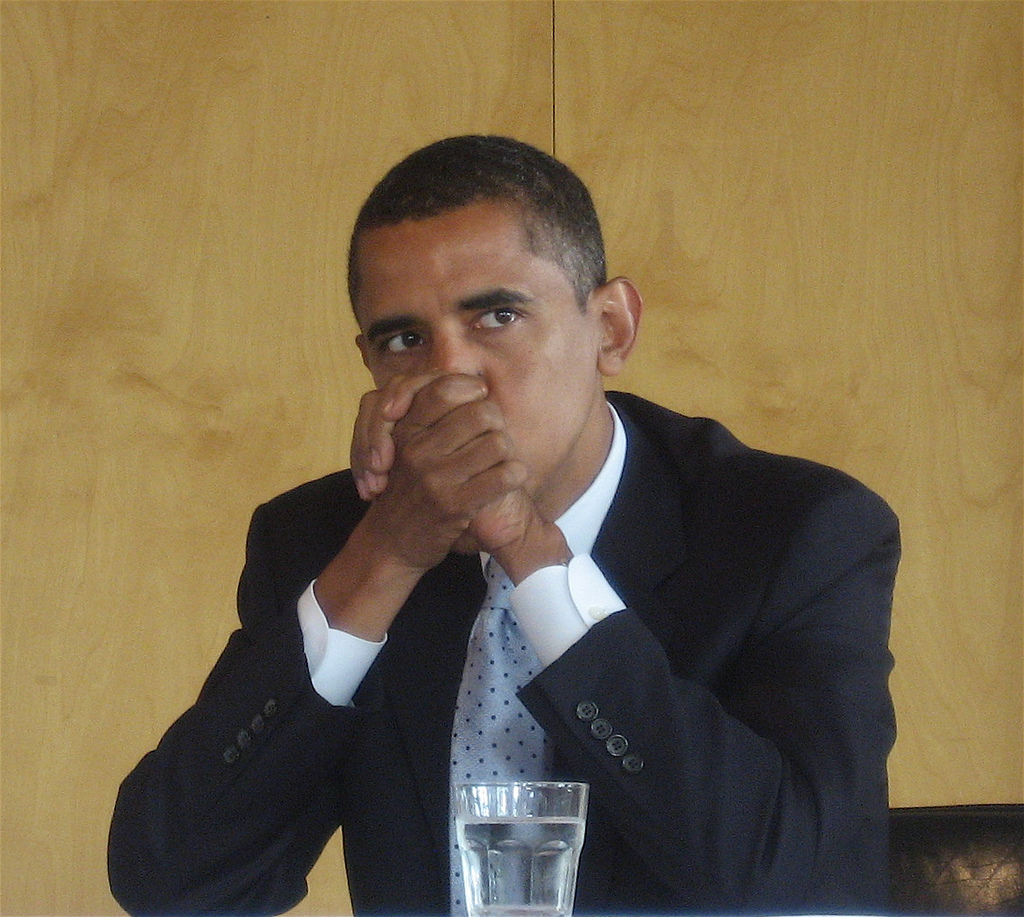

Photo of President Obama courtesy of Steve Jurvetson via Flickr.

The sad experience of the Iran Study Group goes to show that even the advice of the best qualified and most experienced experts will likely be ignored. The people sitting in the seats of power have to do their best so long as they have the President’s confidence. Let’s hope, though that they are reading Lobelog.

With all due respect, this observer would argue that some of our most seasoned Middle East experts were marginalized in the State Department beginning as early as the late 1960’s- and, notwithstanding President Carter’s historic Camp David agreement (or perhaps because of it)- were later purged, and that this trend continued through the Clinton Administration, such that by that time our experienced Arabists who had earlier provided a nuanced understanding of the region, had been displaced by a much more pro-Israeli cadre that were then regarded as our go-to ‘Middle East experts’- persons such as Martin Indyk, Dennis Ross, Aaron David Miller, who were not exactly the unbiased visionaries we needed for a stable long term policy, as opposed to a stalemate in the peace process and an expansion of Israel’s territorial reach.

While Ambassador Hunter’s advocacy of the JCPOA is both realistic and laudable, it would have been helpful to acknowledge Russia’s enormous diplomatic contribution to that agreement, and mention the necessity of cooperating further with Russia, China, Iran and the governments of Iraq and Syria, both re: combatting ISIS, and in facilitating a political resolution of the Syrian crisis.

Furthermore, I would take issue with his interpretation of Madeleine Albright’s famous quotation. “American Exceptionalism” cannot exist without an exceptional strategic vision. She never had it, nor did her colleague and successor once removed, Condoleeza Rice.

If the U.S. is to engage in strategic thinking, then the should not the U.S. be taking the bull by the horns and corral its Turkish, Saudi, Qatari, Israeli, and other allies to stop facilitating ISIS and Al Qaeda, and looting Syria and Iraq, in favor of a positive accommodation with those nations and all others in the region? Until now, the U.S. strategy seems to have been a latter day carryover of the CIA approach beginning with the Allen Dulles, to break each and every country that was not fully allied with U.S. interests, blended with the Oded Yinon plan to break all countries deemed a threat to Israel by creating, at the very least, chaos in the respective country. None of this has recognized the centrifugal differences between each of our regional allies (Israel, Turkey, Saudi Arabia, Qatar and Jordan, etc.) or the risks associated with the tactic of ‘Orange Revolution’- let alone the political and cultural dynamic of the countries we have sought to break- nor the interests of Russia and China. It doesn’t help to characterize Putin as a ‘thug’ (which the West has done repeatedly) as a rationale for avoiding working cooperatively with Russia and China to help bring peace and reconciliation to the region.

Since Obama doesn’t have much time left, he has to devote the last “dance with them that brung him.” Those “special interests” are the “US interests” he is serving right now. Top of the list: the arms industry and the surveillance industry. Therefore, a tsunami of arms and taxpayer money will wash over Saudi Arabia and Israel, and they can just keep right on executing inconvenient people and thieving large swathes of the West Bank with impunity. And given that the GOP presidential candidates are doing such a fine job of fearmongering and making Obama look even weaker, you can be sure that Booz Allen and its fellow contractors are currently working on ever more intrusive, ever more expensive surveillance programs this year.

As for those “continuing efforts by the JCPOA’s opponents — notably the Israeli government and some of its more politically active supporters in the United States, along with some of the Sunni Arab states, led by Saudi Arabia — to undercut the nuclear agreement, or at least limit its scope,” you’d think that Obama and his staff could hardly miss reports on it in all the papers this week, but they can read all the papers they like and it won’t make a bit of difference. They take their orders from the Deep State, whose primary reason for existing is to make sure it can keep on existing.

The only “strategic vision” Obama and his team, crippled by tepid ineptitude, will be working on right now is how to make it to the end of this year.

Ambassador Hunter, since the fall of Soviet Union the west, particularly US, had to find or create a new enemy so the military industrial complex can go on with their programs in developing new arms and more selling arms to someone in order for them to survive. President Reagan found and made his decision! The regions are going to be the ME & A to replace the Soviet. Since the selected regions can NOT and would be of NO CHALLENGES to the west, the US strategy was changed to “create Chaos”! The “chaos strategy” started with encouraging Sadam and supplying him with arms and chemical arsenals to attack Iran in 1980 and also chasing the Soviets out of Afghanistan! The Afghanistan involvement was successful in the eyes of American adminstration because Al-Qaida was created! Then “Counter- terrorism” or “Perpetual War Strategy” evolved from the “Chaos Strategy”! Looking back at the US strategy in the ME & A and in the Eastern Europe, to certain extent, has become anti-Ilamic nations from the Clinton adminstration until today! So president Obama didn’t need to develop his own strategy in the ME & A at all since it was already planned for him. President Obama didn’t need to modify the strategy either because Russia was further weakened until recently when they played a major role in the agreement with Iran and the on going war in Syria!

BOTTON LINE THE “Creating Chaos Strategy” has been working for the US adminstrations for over 35 years! Don’t fix it if not broken! But it is sad when power is being abused!!!

Re: “classical interests”

The author asserts that the US has “classical interests” in the Middle East. Can you believe this perfidious nonsense! This is rather like saying that the mafia has “classical interests” in the extorsion and prostitution rackets.

The US has imperialist interests in the Middle East. That is the unvarnished truth; and it assures these interests by means both legitimate and outright criminal, and with a maximum of dishonesty, treachery, brutality, and hypocrisy.