by Gordon Adams

The famous “wall” is no longer a partisan issue between Republicans and Democrats, between those supporting a wall and those who find the administration’s whole immigration policy, including the wall, tragically inhuman. This battle has moved from a political conflict to a deeper, important institutional struggle over the constitutional authority to determine spending. Republicans need to step back and see what is happening to the institutional power of the Congress as a result of Trump’s actions.

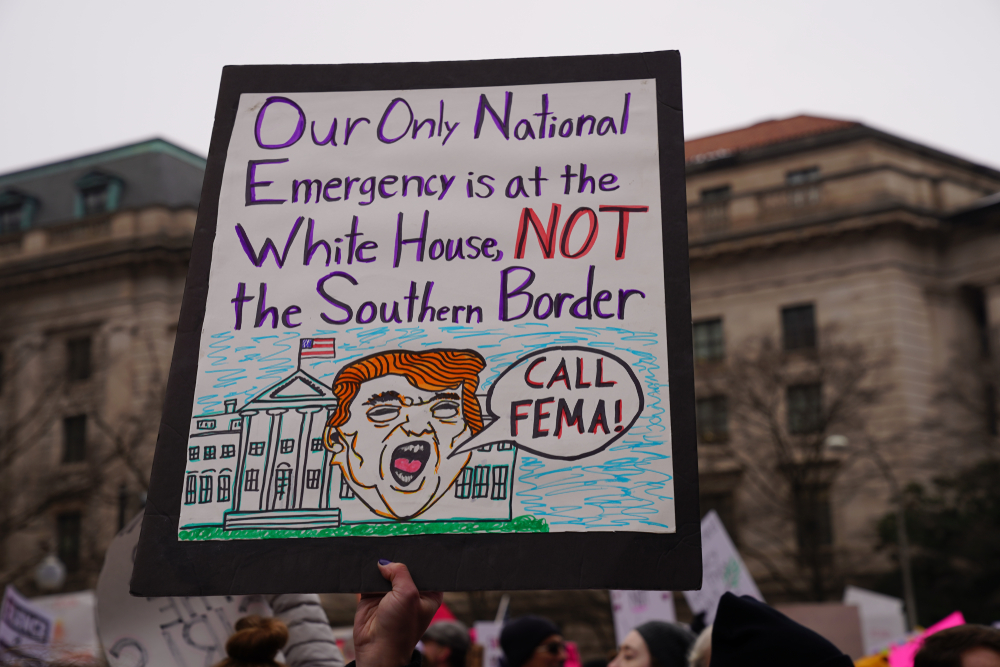

As the press has pointed out, Trump’s declaration of a national emergency is, in fact, quite different from every other such use of this authority since the National Emergencies Act was passed in 1976 The fake “emergency”—which he said he “didn’t need to do” but just wanted to “do it faster”—was expressly declared so he could spend appropriated funds on something he wanted that Congress had rejected in the spending bill he signed when they sent it to him on February 15.

Sounds ridiculously technical, doesn’t it? But this kind of fight—over the power of the purse—has a long history that is important to the protection of America’s democratic institutions. Donald Trump has now posed a direct challenge to Article 1, Section 9, paragraph 7 of the constitution. That short paragraph gives Congress control over spending: “No Money shall be drawn from the Treasury, but in Consequence of Appropriations made by Law.” In other words, Congress has the power and authority over spending.

Congress has jealously guarded this “power of the purse.” It is usually ready for a political fight when presidents try to execute end-runs.

In the early 1970s, when Richard Nixon simply refused to spend monies Congress had appropriated for environmental programs that he opposed, Congress took umbrage and passed the Budget and Impoundment Act of 1974. Under that act, if the president didn’t like what Congress had voted, he had to come back formally to the Congress and ask them, basically, to “take the money back,” by rescinding the original appropriation. The president could ask, but Congress would dispose, as the constitution intended.

I encountered this institutional struggle in my own work in the 1990s, when I was in charge of foreign policy and national security budgets at the Office of Management and Budget. This time it involved something called the “Line Item Veto Act,” passed in 1996. Until that act passed, presidents had to veto an entire spending bill sent by the Congress. They could not dip into the bill and take out specific line items they did not like.

Congress had resisted persistent presidential requests for the authority to eliminate “pork,” line items that would benefit a specific member of Congress and that the president had not asked for in his budget request. In a momentary fit of madness, Congress actually passed an act giving the president this power.

The Clinton administration was the first and only administration to use the line item veto. I worked the first two such veto efforts—on the now-famous military construction act and the defense appropriations act.

Deciding what to veto was a difficult exercise, but we found a way to eliminate more than 40 military construction projects the administration had not asked for but had been shoved into the bill by members of Congress. We got our head handed to us the first time when Congress overturned our veto message on the military construction bill.

More seriously, the chairman of the Senate appropriations committee, Robert Byrd (D-WV), had never liked the Line Item Veto because, in his mind, it was an unconstitutional violation of congressional power under Article 1, Section 9. He took us to the Supreme Court, and we got our head handed to us again when the Supreme Court struck down the statute.

Presidents never like to lose, but the decision was right. Presidents, and others, may not like how Congress votes the money, but they must live with it. This fight is about the power to vote monies and have them spent on what Congress intended, not walls or military construction projects it doesn’t want. This power of the purse protects against tyranny and chief executives who can redirect money on a whim, regardless of what Congress has voted.

The authoritarian in the White House is, of course, ignorant of this history, as well as ignorant of the constitution itself. Hopefully, as this fight wends through the courts, he will learn that whatever his autocratic tendencies, he is not a king.

Thanks for the very good article. Not sure though if Trump will learn about the separation of powers, institutions and the constitution even if the SC strikes down his request!