by Scheherezade Faramarzi

Blood gushes from the dead man’s head, dripping down his face as he sits slouched in the backseat of the yellow Peykan car. Two men search the pockets of the green raincoat that he wears over his army uniform.

A teenager, holding his head and crying helplessly, sits on the side of the road, next to a machine gun.

The camera zooms back on the two older men. They grab the dead man’s arms and clumsily try to drag his body out of the small car. The corpse keeps slipping from their hands until it falls head down on the ground. The rumble of an approaching tank is heard, so the men leave the body dangling from the car. The tank’s occupants salute them, and the men carry on.

The teenager by now is crying hysterically. It was he who had pulled the trigger. He’d clearly never held a gun before, let alone shot and killed anyone. He was just an ordinary kid who, like thousands of others, had gotten too excited about the revolution and had found a lethal weapon in his hand. He didn’t know the identity of the man he’d killed. Even if he knew his name was Major-General Abdul-Ali Badrei, he probably wouldn’t have known that he was the shah’s powerful commander of the Royal Guard and Ground Forces.

The graphic and gory details of Badrei’s murder was captured by a relative of mine, who never left home without his video camera during the tumultuous months leading to the overthrow of the shah. He was at the scene of the attack on the Saltanatabad barracks that Sunday morning 40 years ago, on February 11, just hours before the Pahlavi dynasty and the Iranian monarchy came to an end.

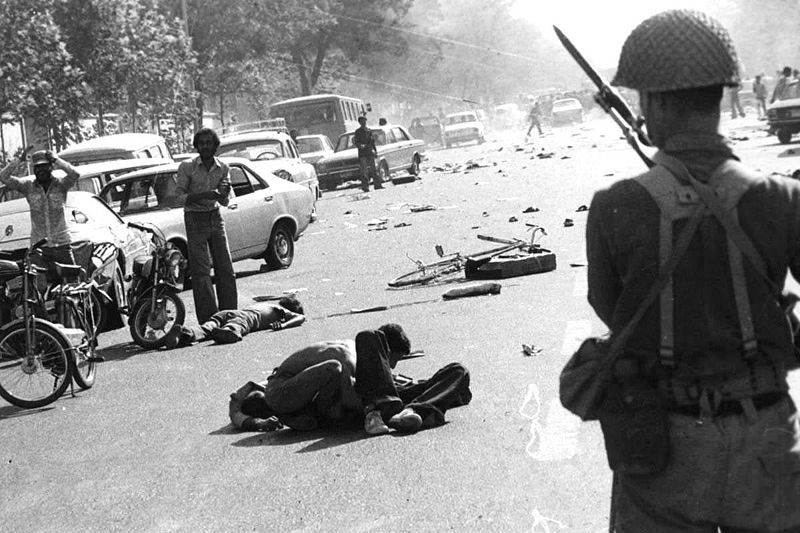

Everything was happening very fast that morning, too fast for people to realize what was really going on. A couple of hundred people stormed the Saltanatabad barracks in northern Tehran forcing soldiers to flee. At the edge of the base, three men ordered a yellow Iranian-made Peykan to stop. The man sitting in the back of the car—Badrei—tried to trick them: he told them that if they hurried, they could capture the commander of the base who was trying to escape. Then he ordered his chauffeur to drive on. The car had moved only 20 yards when the teenager fired three rounds from his machine gun, hitting Badrei in the back of the head.

The three men probably had not heard the news that at 11 that morning Badrei and 49 other military commanders had declared their neutrality in order to prevent further bloodshed and had ordered their men to withdraw to the barracks. Only the elite Imperial Javidan Guard (the Immortals) was defiant. Badrei, one of the shah’s most loyal military commanders, had wept when he watched the monarch’s departure into exile on television two weeks earlier. Despite the agreement to surrender, the papers allegedly found in his pocket indicated that he was plotting a coup.

It was chaos all over the capital. People had taken matters into their own hands. The violence and disturbances reached their peak on Saturday, February 10, prompting Tehran’s military governor to declare a curfew starting at 4:30 in the afternoon (instead of the 11 p.m. curfew that had been in place in previous months), fueling rumors of a possible coup.

Ayatollah Ruhollah Khomeini, who had returned from exile nine days earlier to take control of the revolution, swiftly ordered his supporters to ignore the curfew and flood the streets.

People set up checkpoints at street junctions, burned tires and wood, and destroyed cars. Others rushed the wounded to hospitals and the dead to morgues—casualties of clashes with the army. The shah’s invincible military disintegrated much sooner than anticipated.

As soon as Khomeini called on the people to defy the 4:30 p.m. curfew, a couple of men rang the bell at my aunt’s house on Doawlat Street in northern Tehran asking to use the flat roof to throw stones at the soldiers stationed at the checkpoint on the street below in the event they were to fire at the crowd.

During the previous months of martial law, soldiers’ terrifying shouts ordering drivers to stop, screeching brakes, and occasional bursts of gunfire had become part of the night life on narrow Doawlat Street.

Fortunately, on that fateful February evening, the soldiers didn’t shoot, so the dozen men who took position on my aunt’s roof went home. However, clashes throughout the city between the army and revolutionaries claimed 126 lives and injured 634 people.

Ushering in the Revolution

The next morning, Tehran was rife with rumors and excitement. I left my aunt’s house to look around. It was cold and overcast. Trucks filled with young men and women carrying guns, flashing the V for victory sign and shouting patriotic songs sped by. They were off to conquer prisons, army barracks, and police stations.

People were talking about mobs attacking one of the shah’s notorious Savak secret service headquarters. One of them was near my parents’ home in the Saltanatabad neighborhood. By the time I arrived there, the place had been sealed and they were not letting anyone inside. People spoke of torture chambers and “ovens made in USA.” There were rumors of acid “pools” where prisoners were thrown. Some of these chambers were later shown on television.

Savak, established with CIA help in 1957, was Iran’s most hated and feared institution because of its torture and execution of the shah’s opponents. During the months leading up to the revolution, the opposition cited Savak as an example of America’s direct influence and domination of the country to rally support for the rebellion that eventually toppled 2,500 years of monarchy.

That night, like most Iranians, I was glued to the TV set watching history unfold. The transmission began with an old and very popular national anthem, “Oh Iran, the Frontier of Jewels” that the Shah had replaced long ago with his imperial anthem. A beaming anchor, Ali Husseini, became an instant celebrity when he announced with clenched fists the triumph of the revolution. He became the face that ushered the revolution into Iran’s homes.

Until that night I hadn’t thought about what lay ahead. Unlike most Iranians, I had experienced the taste of freedom during my years in England. It tasted really good. It gave me strength and reason to care about the world and what was going on around me. Many who lived their entire lives under the tyranny of the shah now faced the power of that word. Free to do what? Free from the shah and his autocratic rule? What was going to happen now? Islam rules. No, I didn’t want any religion to rule. I had studied sociology in England, and my teacher had taught me that religion was the opium of the people. I began to panic. What next?

Husseini, the anchor, his excitement turning to fear, urged viewers to rush to the TV station to break a siege laid by the “remaining forces of the defunct shah.” Within minutes, thousands of people had poured onto Jam’e Jam, the TV and radio broadcasting station in northern Tehran. About an hour later, Husseini was begging people again—this time to stop coming as there were more people than needed. Forces still loyal to the Shah had retreated. He thanked everyone for their heroic presence.

A Bitter Turn

Soon after the revolution triumphed, disillusion and despair replaced the great optimism and hope of the Iranian people. Endless executions of former regime officials, with gruesome photos of their bodies splashed on the front pages of newspapers, dented this optimism—even among strong supporters of the clergy and the so-called disinherited masses whose plight all political groups claimed to champion. Gradually, these people began doubting the sincerity of the clerics and Islamic leaders whose words they had accepted without question.

The activities of the komitehs—one of the most intimidating and bullying institutions of the revolution—disillusioned Iranians who had supported the shah’s overthrow. Each day, a more severe blow landed, including the shutting down of independent publications that had sprung up following the revolution and more incidents of vigilantes attacking unveiled women, even throwing acid on their faces—though the veil was not yet mandatory. Government offices gradually required female employees to wear the veil, and there were fears that the policy would soon extend to the private sector and the streets. Several anti-veil demonstrations had failed to soften the government’s resolve to make the headscarf mandatory.

In summer 1980, Khomeini decreed that no woman could go to work unless she were fully covered, resulting in the dismissal of a large number of female employees. Later, his regime prohibited women from shopping without a veil. The dress code became more restrictive as time went on. Eventually, vice squads patrolled the cities on the lookout for “moral offenses.”

Ordinary secular people were sidelined and gradually regarded as a threat, as remnants of the monarchy, too liberal to be trusted. They were labeled as taghuti (pagans) or gharbzadeh (Westernized). These two labels were to cost them dearly because they alienated them from a movement they had initially supported.

People were perhaps so overwhelmed by the need to get rid of the shah that they failed to notice the extent to which religion had seeped into the movement. Even when Khomeini became a near idol, they were thinking they would use him as a means to get rid of the shah. A secular democratic state was the goal. Khomeini was the only one who could unite the people against the shah, and for that moment they had a common enemy. It wasn’t that they failed to understand, but there was nothing else they could do. They pretended that they did not see, or they justified their support for the forces of the revolution as the only way to get rid of the shah. Let the Shah go, and que sera sera. It was too late now. The shah had left his people a choice between the Savak and the mullahs. And they chose the mullahs.

Extremely disappointed with the turn of events, I decided to go away for a little while. Around my neck I tied a small black-and-white silk scarf that matched my short-sleeved white dress and that I could swing onto my head if harassed by airport vigilantes. It was 15 years before my next visit to Iran.

Scheherezade Faramarzi has covered the Middle East since 1978.

We know that the PLO came around to help Khomeini.

The Shah could have brought out the largest military in the Middle East to preserve the peace. But he didn’t.

Put those two factors together.

But that was then. Going forward the madmen are very afraid of free speech. Just watch them moan here at me.

Who would have thought that a few old men could stop the rape and pillage of the region by US/UK/Israel/Saudi Arabia now going into its 70 years. Mohammad Reza Shah was just an order taker like most despots on the military complex payroll.

I missed all that but the ultimate sacrifices made by the ordinary people of Iran to free themselves of the yoke of an extended Qajari’s dynasty in 1979 is commendable! Good riddance!