by Mahmoud Pargoo

Saudi Arabia’s decision to sever ties with Qatar in response to the latter’s claimed support of terrorist organizations such as the Muslim Brotherhood as well as its relationship with Iran has raised a crucial question. Namely, is there any commonality between Iran and the Brotherhood that would make both enemies of Saudi Arabia? Alternatively, is the linking of the two in the recent diplomatic upheaval only a matter of coincidence? Further complicating this issue is the recent rise in sectarianism in which the Brotherhood has sided with its Sunni coreligionists to condemn Shia Iran.

Iran and the Brotherhood are sometimes referred to as “the best of enemies,” sometimes as perennial friends. Especially interesting is the avalanche of Saudi-affiliated propaganda that demonize the Brotherhood over its lax and unorthodox attitude toward Shia and its hidden organizational connections with Iran. Though these claimed logistical links between the two deserve critical scrutiny, there are traces of truth in the Brotherhood’s ideological affinity with Iran.

Further, against the conventional wisdom that dictates that everything in the Middle East be seen through a sectarian lens, placing these ideological commonalities in a wider historical context yields novel patterns of political alliances. These emerging contours could shift the existing sectarian battlegrounds to entirely new and unimagined frontiers.

Islamic Unity

The issue of the Muslim Brotherhood’s advocacy of Islamic unity, thus, its relatively softer position toward sectarian divides inside the Islamic world, goes back to the early modern era to Jamal al-Din al-Afghani. Al-Afghani was a Shi’a clergy who became a rising star in the Sunni reformist movement in the late 19th century in Egypt, Ottoman Empire, and Afghanistan. Among his intellectual pan-Islamist heirs were a revolutionary Iranian cleric of Shia persuasion and a Sunni Egyptian intellectual who met in 1954 in Cairo to discuss the malaise of the Muslim world and to focus attention on Islamic unity as a way to emancipate the ummah.

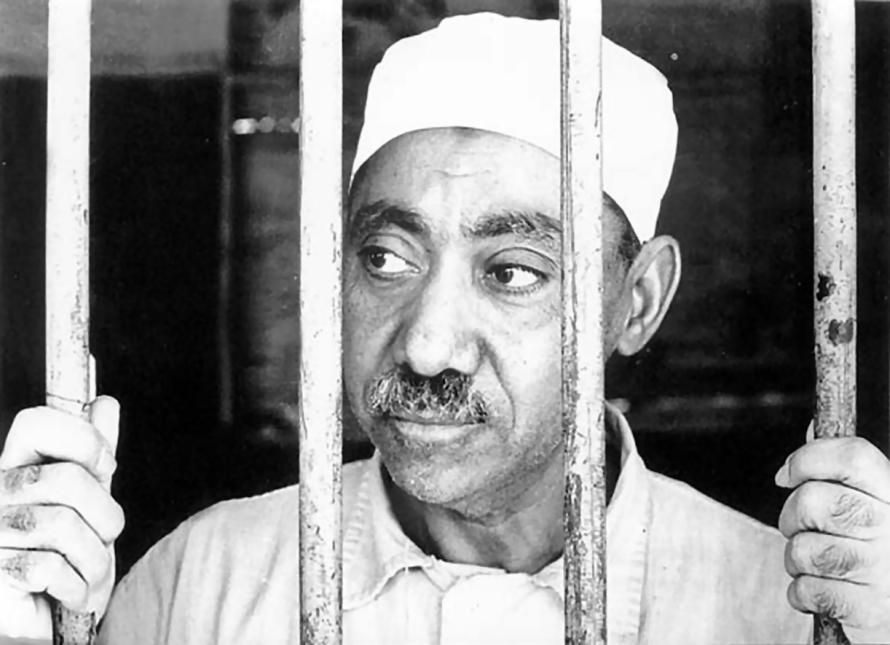

The former, Sayyid Mojtaba Navvab Safavi, a role model for the later young revolutionary clergies of Iran, founded Fada’iyan-e Islam organization to establish an Islamic government in Iran. The latter, Sayyid Qutb, was an educator-turned-preacher who later became the spiritual leader of a militant branch of the Brotherhood, one of the most influential organizations throughout the Islamic world. Ironically, both men were executed by their governments with the silent consent of the traditional religious establishments of their respective countries: Navvab Safavi in 1955 for his involvement in the attempted assassination of Prime Minister Hosein Ala and Qutb in 1966 for attempts to overthrow the Egyptian government by writing his famous book The Milestones. What brought them together was their passion for the emancipation of the Muslim world from the yoke of imperialism and to establish their version of Islamic government. Toward this noble end, both were willing to ignore sectarian differences between Shi’a and Sunni Islam.

The biggest obstacle to achieving the Muslim emancipation, Navvab and Qutb believed, was the coalition of secular dictators of the Islamic world and the traditional clerical establishment. Later, this line of thought became the master narrative of the two movements of Islamic Revolution of Iran and the global Brotherhood. In Iran, Ayatollah Khomeini campaigned against both the deep-seated political quietism of the clerical establishment and Muhammad Reza Shah’s monarchical rule. In many Sunni countries, the Brotherhood did the same within their local context and with a Sunni jargon.

Republican Islamism

The second element shared by both revolutionary Iran and the Muslim Brotherhood is a model of political Islam that uniquely combined popular sovereignty and Islamic values in the paradoxical phrase, “Islamic Republic.” This hybrid theory departed from the long-seated Sunni model of functional differentiation between the political and the religious in Islamic history and has invited fierce opposition from both clerical establishment and the throne. In Saudi Arabia, Islam and the state are two separate entities that have come together only on the basis of the exigencies of practical politics. Hence, Saudi Arabia supports a minimalist, literal reading of Sharia law in which what matters are symbolic private laws and issues of personal piety including the hijab, abstinence from alcohol, marriage and divorce, and so on. According to this pattern of interaction between mosque and state, Islamic authorities don’t intervene in the larger political issues of foreign policy and macroeconomics, which goes against the version of Islam both Iran and the Brotherhood advocate.

Saudi Arabia throughout its modern history has suffered from two legitimacy crises that has made it a perfect grounding site for the Republican Islamist critique. On the one hand, there is Saudi Arabia’s geopolitical alliance with the West and especially the US which has come to be seen an archenemy of Islam. On the other hand, its monarchical system of governance has been ridiculed as a symbol of Muslim backwardness.

Based on the changing geopolitical environments, the kingdom has defined new friends and foes to tackle these existential crises. It has used Salafi Islam to target communism as the greatest threat to Islam in order to divert the assail of criticism pointed at it. It has funded jihadists in Pakistan and Afghanistan. It has assailed the Arab nationalism of Nasser. More recently, however, the most vigorous ideological threat to the Kingdom has come from the Iranian Revolution. The Saudi counterattack has also been calculated and efficient. First, the Saudis actively supported Saddam in the eight-year war against Iran, which prevented the revolution from spilling over to neighboring countries. Second, Riyadh launched an all-out sectarian soft war to discredit revolutionary leaders as Shia heretics that orthodox Muslims shouldn’t follow. This strategy effectively neutralized the Iranian threat in the non-Shia Islamic world as the revolution has come to be recognized increasingly by its distinctively Shi’ite identity.

The Brotherhood, however, was a dormant volcano. Its looming threat to Saudi-style monarchies resurfaced in the 2000s when Brotherhood-affiliated parties claimed power in several Muslim countries. However, the immediate danger was not felt until the advent of the Arab Spring. Once again, Saudi Arabia has extensively capitalized on sectarianism, this time not to contain Iran but to curb the threat of republican Islamism under the banner of fighting Shia expansionism. Iran also contributed to the credibility of this narrative by its unconditional support of Bashar al-Assad’s regime as well as further using sectarian rhetoric to mobilize Shia to fight in Syria.

Iran and the Muslim Brotherhood share some commonalities. However, more importantly, the issue of Shia Iran is but a façade that helps to distort and hide the real contours of political alignments in the post-Arab Spring Middle East. As one of the most popular Arab and Islamic movements among both the educated and the grassroots, the Brotherhood is at the heart of this threat to Arab monarchies. What lies beneath the surface of the current chaotic complexity of the Middle Eastern politics is a competition between traditional monarchism as represented by Saudi Arabia and Brotherhood-like republican Islamism that Iran also shares.

Mahmoud Pargoo is a PhD candidate at the Institute for Social Justice at Australian Catholic University in Sydney. He writes on the Middle East and Islam. Photo: Sayyid Qutb