by Magnus Taylor

There was guarded hope in Khartoum when the U.S. government removed many of its economic and trade sanctions on Sudan in October 2017. Officials thought Washington would move forward with normalising relations, the next step being to strike Sudan from the U.S. State Sponsors of Terrorism list. That would allow the Nile basin country to obtain relief from its $50 billion international debt and attract external investment, both of which are essential for saving Sudan’s failing economy.

The economy has hit rock bottom. It remains crippled by the loss of millions in annual oil revenue since South Sudan seceded in 2011. After a new budget was announced in early January 2018, which included the devaluation of the Sudanese pound against the dollar, inflation spiraled upward. Bread prices also more than doubled after cuts to subsidies on wheat imports.

The runaway prices, along with anger at the mismanagement of the economy and corruption sparked protests in January 2018, resulting in hundreds of arrests – including of several opposition politicians. Police beat protesters, killing at least one. Following pressure from the U.S. and European Union some of the detainees were released a few days ago. Many others remain in prison without charge.

Khartoum’s optimism for a quick normalisation of its relations with the U.S. after economic sanctions repeal was premature. Indeed, the U.S. had been clear that this would not happen without further tangible progress from the Sudanese government, including improvements to its human rights record.

In November 2017, U.S. Deputy Secretary of State John Sullivan travelled to Khartoum, reiterating that phase two of U.S. engagement, which would lead to further lifting of sanctions – including removal of Sudan from the terrorism list – would require Khartoum to make such reform.

Khartoum Plays the Field

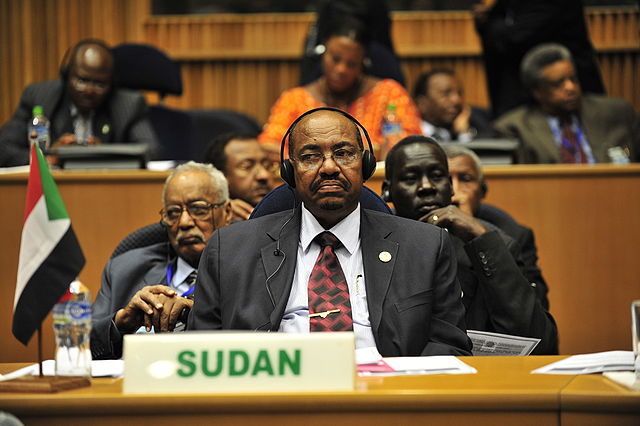

Since then, Khartoum has signaled that it can look for support elsewhere. Shortly after Sullivan’s visit, President Omar al-Bashir flew to Moscow, where he secured a deal from his counterpart Vladimir Putin to buy Russian wheat at a discounted rate. Bashir also caused consternation in Washington by declaring his support for Russia’s intervention in Syria and criticizing U.S. Middle East policies.

Sudan’s leaders still view rapprochement with the U.S. and other Western countries, as well as with the European Union, as critical in the long term. But in the meantime, the regime needs to cultivate friends who can help it fend off immediate threats, notably those related to its lagging economy. In this spirit, Bashir has adapted to an increasingly thorny geopolitical landscape, both in the Horn and beyond, by moving from one alliance to another, juggling rivalries among his potential allies. This has delivered some gains to his government, but they are likely to prove short-term at best.

Nowhere is this strategy more evident than in Sudan’s relations with the Gulf states, particularly Saudi Arabia, the United Arab Emirates (UAE) and Qatar. Enticed by promises of money for infrastructure and agriculture development, as well as deposits in the Sudanese Central Bank, Sudan – a close ally of Iran during the 1990s and early 2000s – switched its allegiance to the Arab Gulf bloc in 2014. The biggest consequence of this realignment was Khartoum’s dispatch of thousands of troops to Yemen to join the Saudi-led coalition fighting the Huthi rebels.

Khartoum is disappointed, however, with the financial rewards it has received in return, despite also benefitting from Saudi lobbying of the U.S. over sanctions repeal. In mid-2017, when tensions escalated between Qatar and the Saudi-UAE axis, Khartoum chose not to break with its longstanding ally in Doha, preferring to keep its options open.

Tensions with Egypt

Sudan’s relations with Egypt, its neighbour to the north, are also strained. A December visit of Turkish President Recep Tayyip Erdo?an – a close ally of Qatar – to Khartoum brought simmering tensions out into the open. Erdo?an announced $650 million in investments, including a Turkish commitment to restore and lease the Ottoman-era Red Sea port on Suakin Island.

Turkey’s sudden interest in Sudan is of particular concern to Cairo as both Doha and Ankara support various chapters of the Muslim Brotherhood across the world. Since Abdel Fattah el-Sisi seized power in July 2013 from President Mohamed Morsi, a Muslim Brotherhood leader, Cairo has presumed the Bashir regime to be close to the Islamists. Its willingness to allow Muslim Brothers expelled from Egypt to visit Sudan is a sore spot for Sisi.

A graver diplomatic problem is Sudan’s perceived divergence from Egypt’s opposition to the Grand Ethiopian Renaissance Dam, which Ethiopia is building on the Blue Nile. Khartoum claims neutrality in negotiations over the dam, but in reality has developed its own distinct position that departs from its earlier support for colonial-era agreements on the allocation of Nile water, which heavily favour Egypt.

Sudan will benefit from the dam’s construction: it will supply the country with cheap electricity, as well as Nile water for greatly expanded agricultural irrigation, particularly in Blue Nile state. Such ambitious plans worry Cairo, which sees upstream projects as a major threat to its own water supply and, therefore, its stability.

The ongoing war in Libya has caused tensions too. Khartoum is concerned that Darfuri rebels, now based in southern Libya, have served as mercenaries for General Khalifa Haftar, de facto ruler of Libya’s east, who is backed by Egypt and the UAE. In return, the rebels have received money, guns and equipment, which Khartoum fears they will use to restart their rebellion. When Sudanese Liberation Movement insurgents briefly re-entered Darfur (from both Libya and South Sudan) in May 2017, Khartoum angrily accused Cairo of arming them.

Escalation in Eritrea

These frictions came to a head in January 2018 when, amid the economic crisis, reports emerged that Egypt had deployed troops in Eritrea (it appears now that Cairo sent only a small number of advisers and trainers). In response, Khartoum closed the border with Eritrea, declared a state of emergency in the region and deployed additional militia forces to the area without entirely explaining why. It may have been a ploy to divert public attention from worsening economic woes.

A meeting between Presidents Bashir and Sisi on the margins of the African Union summit in Addis Ababa in late January, followed by a visit to Cairo by the Sudanese foreign minister in early February, helped de-escalate tension. But they have done little to address the disagreements underpinning it.

With the dividends of U.S. engagement still mostly unpaid, Khartoum’s foreign policy will likely continue to evolve with shifts in relations among richer and more powerful players. Sudan’s economic crisis increases pressure on President Bashir at home as regional politics are becoming ever more complex. Recent shifts of key regime figures, including at the helm of the powerful National Intelligence and Security Services, show that the president is keen to shore up his own position.

Khartoum’s international standing is higher than it was some years ago, when it was a near pariah due to the atrocities of wars in Sudan’s peripheries, and it has long proven adept at navigating choppy geopolitical waters. But its ability to do so is likely to be tested further over the coming months.

Magnus Taylor is an analyst on the Horn of Africa for the International Crisis Group, where this essay originally appeared.