by Peter Jenkins

A new Brookings Institution paper, “Preventing a Nuclear-Armed Iran,” has rightly attracted considerable attention. The author, Robert Einhorn, has a distinguished record and was Special Adviser for Non-Proliferation and Arms Control at the State Department from 2009 to 2013. His recommendations must be seen as authoritative.

The paper addresses the issues that are at the center of the ongoing negotiations in Vienna between Iran and the P5+1 (the US, Britain, France, China, and Russia plus Germany). Einhorn recommends key requirements for an acceptable agreement with Iran — requirements designed to prevent Iran from having a rapid breakout capability and to deter a future Iranian decision to build nuclear weapons.

Preventing a rapid breakout capability

Iran’s development of a capability to enrich uranium has been at the core of Western concerns about Iran’s nuclear programme for over a decade. The two enrichment facilities that Iran has built, at Natanz and Fordow, are being used to produce low-enriched uranium for civil purposes but could be used to produce highly enriched uranium for military purposes.

The Nuclear Non-Proliferation Treaty (NPT) prohibits the manufacture of nuclear weapons by states such as Iran but does not prohibit the possession of enrichment facilities. The West’s negotiators therefore have a delicate task: they must contrive to persuade Iran to accept restrictions on its use of this technology — restrictions that would give the UN Security Council enough time, reacting to evidence, to prevent Iran from producing enough weapons-grade uranium for one device (i.e. from “breaking out”).

Einhorn explains that the breakout timeline depends on the numbers and types of centrifuges used and on the nature of the uranium feedstock available for a breakout attempt (for instance, if the feedstock is already low-enriched much less time is required than if it is un-enriched).

He goes on to describe the implications of limiting Iran to between 2000 and 6000 first-generation centrifuges. This creates the impression that these are the sorts of numbers that ought to be agreed to in Vienna. That is unfortunate, because Iran has already installed 19,000 first-generation centrifuges and is using 10,000 of them — and Iran’s President Hassan Rouhani has ruled out the dismantling of any existing capabilities (which his political opponents could portray as a humiliating surrender of Iranian rights).

Einhorn’s choice of what looks like an unrealistically low figure appears to stem from wanting to give the UN Security Council several months to react to evidence of a breakout attempt. However, as he himself implies, several months would be useful only if the Security Council were to want to impose sanctions before opting for force. In reality, since sanctions have proved ineffective as a tool for coercing Iran, the council would be well-advised to opt for force within a matter of days, and could do so if the P5+1 had pre-agreed that this would be the most appropriate response (see below).

A related concern is possible Iranian development of more advanced centrifuges. With a few thousand third-generation machines, using a low-enriched feedstock, only a few weeks would be required to break out. This concern could be resolved by placing limits on the scope of Iran’s centrifuge R&D, as Einhorn recommends. But tight limits may not be negotiable.

Yet another concern relates to the plutonium-producing potential of a 40MW reactor under construction at Arak. Einhorn describes ways in which this potential could be reduced. Recent Iranian statements suggest that they, too, are working up some proposals. So this concern is likely to be largely allayed, although the risk of a plutonium-based breakout may not be totally eliminated.

Deterring an Iranian decision to build nuclear weapons

In the absence of watertight solutions to these breakout concerns (or to concern that Iran might break out using a small clandestine facility) the West’s negotiators will do well to devote at least as much effort to deterring breakout as to trying to make rapid breakout impossible.

Since 2007 US National Intelligence Estimates have drawn attention to the importance of influencing the cost/benefit calculations of Iran’s leaders, implying that this is likely to be the most effective way of ensuring that Iran does not become a nuclear-armed state.

The framers of the NPT perceived that the treaty’s impact would hang on the ability of parties to recognise a national security interest in supporting nuclear non-proliferation and disarmament. Consequently the only deterrents envisaged in the treaty are verification of nuclear material use by the International Atomic Energy Agency (IAEA), the risk that non-compliance will result in UN sanctions or authorisation of force, and the certainty that non-compliance will lead to a loss of prestige and exclusion from the society of the treaty’s adherents (currently 190 states).

Since 2003 President Rouhani has shown that he understands all this very well. He knows that Iran would pay a high price for breaching its non-proliferation obligations and that acquiring nuclear weapons would bring no benefit, since Iran is not in need of a nuclear deterrent. The signs are that his political opponents, too, have figured that out.

All this needs to be borne in mind when determining whether any additional (going beyond the NPT) deterrents are necessary in the current context.

Einhorn believes that they are. The most questionable of his recommendations are that:

- The Security Council should agree in advance on how to react to any evidence of an attempt to break out or other serious violation of the agreement under negotiation in Vienna;

- The US Congress should pass a standing authorisation for the use of military force (AUMF) in the event of evidence that Iran has taken steps to abandon the agreement and move towards producing nuclear weapons;

- The US administration should indicate publicly how it would react to such evidence.

These recommendations betray a flawed understanding of Iranian psychology. Such public threats would be seen in Iran as humiliating, and would be resented. That resentment could be used to stir up opposition to the agreement and could even end up providing a motive for ditching it. The threats would serve no practical purpose since leading Iranians are already well aware of what they would risk were they to attempt breakout.

More in keeping with Iranian psychology and a more effective deterrent would be a private P5+1 intimation that they will be united in urging the Security Council to authorise force in the event of evidence of a breakout attempt. Nothing more is needed. Iranian diplomats are highly intelligent.

Conclusion

This paper is heartening. It offers reason to think that the Vienna negotiators can succeed in producing a resolution of Western concerns that Iran will have an interest in respecting. However, as Iran’s Foreign Minister Mohammad Javad Zarif likes to remind us, a resolution will require flexibility from both sides. The West must try to avoid the over-bidding (in pursuit of over-insurance) that doomed the 2004-05 negotiations between Iran and the E3 (the UK, France and Germany).

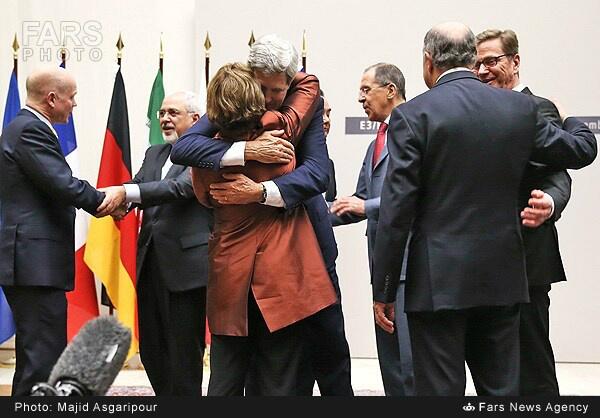

Photo: Representatives of Iran and the P5+1 celebrate after an interim nuclear deal is signed in Geneva, Switzerland on Nov. 24, 2013. Credit: FARS News/Majid Asgaripour

Mr. Canning says, “sound analysis”, and sound it is:

Here is Mr. Jenkins’ most important paragraph:

“These recommendations betray a flawed understanding of Iranian psychology. Such public threats would be seen in Iran as humiliating, and would be resented. That resentment could be used to stir up opposition to the agreement and could even end up providing a motive for ditching it. The threats would serve no practical purpose since leading Iranians are already well aware of what they would risk were they to attempt breakout.”

And so, if the threats would serve no practical purpose, what remains is their potential to scuttle the agreement. It is quite clear that that is neither in the American interest nor in that of Iran.

By the way, if Mr. Einhorn’s report contains the basic outline of the negotiations, why is he leaking it from his position at Brookings?

I too see that passage as the most important in a great piece. Thanks, Hunter.

A US “authorization for the use of military force” (AUMF) based on “evidence” that Iran is “breaking out” is a highly dangerous and counter-[productive proposal. Iran and many of us recognize how easily faulty evidence (witness WMD pre-Iraq war) can be generated without critical investigation, and lead to a pointless war, ESPECIALLY if the AUMF is sitting there, ready to go without any congressional debate. There is every reason to believe that Netanyahu’s Israel would be the first in line to provide such bogus evidence in order to bring about the combined US-Israel attack that Israel keeps promoting. Iran could well refuse to accept an agreement that puts it under such a Damocles’ sword.

A second point, alluded to by another commentator, is that imposing punitive consequences to prevent an Iranian breakout triggers all Iran’s hot buttons based on a long history of Western aggression, and is not conducive to a sustainable agreement. More effective would be US and Western acknowledgement of Iran’s right to exist free of daily threats of attack, and more potently, recognition of Iran as a major power in the middle east. In this regard, Iran should be invited to participate in negotiations on Syria, Iraq, Afghanistan, and drug smuggling — all areas where the US and Iran have interests in common. This, in addition to increased trade with the West resulting from diminished sanctions, would be a hundred times more powerful in discouraging any Iranian push towards a nuclear weapon, than military threats, and is t likely to encourage Iranian nuclear concessions.

I heartily agree Iran should have been a participant in efforts to resolve civil war in Syria by diplomacy. And should be. Ditto as to Afghanistan.

Fine post.

Will the US similarly threaten the 40 other nations tha already have this rapid breakout capability, or does Einhorn imagine that the Iranians are willing to be second class members of the NPT just to make Israel happy? “Rapid Breakout Capability” is nonsense, it is being used to scaremonger about Iran in the absence of any actual evidence of a weapons program. If Iran wants a breakout capability, it is fully entitled to it as a sovereign nation, and under the NPT itself. The Einhorns of the world don’t get to rewrite treaties willy-nilly to suit themselves.