by Austin Bodetti

Little about Yemen would suggest that it represents the next frontier for renewable energy. Since 2015, the Yemeni government, Saudi Arabia, and the United Arab Emirates have fought Iranian-backed Houthi rebels for control of the country as human rights activists accuse both sides of participating in war crimes. Concurrent cholera outbreaks, famines, and other humanitarian crises have left Yemenis no time to devise a comprehensive response to climate change and environmental degradation. Despite these dire circumstances and in part because of them, solar power has taken Yemen by storm in recent years.

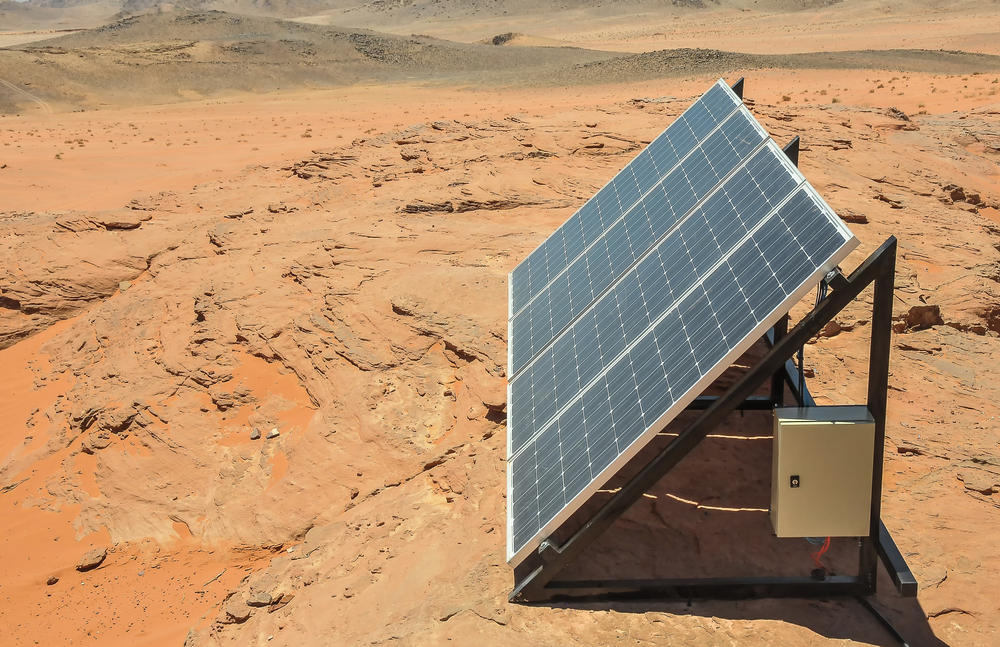

The Yemeni civil war has led to the destruction of countless electric power systems, more than halving the availability of electric power throughout the country. The conflict has also contributed to a shortage of fuel, which accounted for 70 percent of electricity generation in Yemen in 2010. Given these challenges, Chinese-manufactured solar panels offer the best alternative.

“For most Yemenis, there was no choice but to buy solar panels for light and their basic electrical needs,” Safia Mahdi, a Sanaa-based journalist who won recognition for documenting this phenomenon, told LobeLog. “The majority of Yemenis have relied on solar panels for the duration of the war.”

Residents of Sanaa, where blackouts were commonplace well before the Yemeni civil war, turned to solar power after Emirati and Saudi airstrikes damaged electrical grids in the Houthi-held capital in 2015. The trend soon reached the cities of al-Hudaydah, Ibb, and Taiz as well as rural areas—spanning territories under the control of the Houthis and the Yemeni government alike. For its part, civil society facilitated the spread of solar power in Yemen through projects such as Green Pages, an initiative to help Yemenis affected by the energy crisis determine how and where to buy solar panels.

“Solar power’s use in homes is mostly limited to running home appliances, namely turning on lights, powering televisions, washing clothes, and charging phones,” said Ibrahim Youseffi, an electrical engineer in Sanaa who has worked with several aid agencies. “Those with money have systems large enough to operate air conditioning as well as fans and pumps.”

By January 2016, over 40 percent of Yemenis had come to rely on solar power to meet their basic needs. Solar panels had even begun to appear mounted on ice cream carts and motorized wheelchairs in Sanaa, speaking to the accessibility of solar power in a country where millions were still struggling to find enough food and water.

Yemenis have deployed solar panels against these shortages too. Taking advantage of infrastructure designed by the International Organization for Migration, the Yemeni government uses 940 solar panels to deliver water to tens of thousands of Yemenis daily. Solar power has also allowed Yemeni farmers to continue running the pumps necessary for lift irrigation.

“In the past, many rural areas and even parts of some cities didn’t have electricity,” said Helen Lackner, a research associate at the London Middle East Institute and author of Yemen in Crisis: Autocracy, Neoliberalism, and the Disintegration of a State. “Today, Yemenis are much more reliant on solar power and less so on the public sector. Most Yemeni households have solar panels. Solar power has saved Yemeni lives in addition to improving living conditions in Yemen enormously.”

The international community is moving to support these Yemeni efforts. The European Union and the United Nations launched the Enhanced Rural Resilience in Yemen Program in 2016 to boost the use of solar power in the governorates of Abyan, Hajjah, al-Hudaydah, and Lahij. The UN also noted on Twitter that it has given Yemeni fishermen in the Red Sea GPS navigation devices powered by solar panels, which could help fishing vessels evade errant shots from Saudi warships. The World Bank, meanwhile, announced in 2018 that it would fund the deployment of solar panels in Yemen’s rural areas.

“The international community can lend further assistance by building factories for solar panels in Aden or elsewhere and educating Yemenis on how to use the technology effectively,” Moosa Elayah, a senior scientific researcher at the Center for International Development Issues Nijmegen, told LobeLog. “Foreign aid agencies should launch programs and expand on the efforts of Yemeni NGOs.”

Yemen’s unprecedented success with solar power could act as an example for other countries that have faced energy crises induced by civil wars. From Afghanistan and Iraq to Libya and Nigeria, the rest of the Global South can emulate Yemen by embracing the benefits of sustainable energy.

“Politically, it makes enormous sense for other countries to adopt solar power,” said Lackner. “Yemen could be an example. These solutions are coming from the people as popular initiatives.”

The adoption of solar power by Yemenis across the country’s geographic, political, and sectarian divides further suggests that Yemen can mobilize a national response to the wider challenge of global warming even if the Yemeni civil war persists. In fact, the future of the Middle East’s poorest country may depend on Yemen taking action to preempt an environmental disaster.

For many Yemenis, climate change represents a matter of life and death. Global warming has accelerated desertification, a threat to the viability of agriculture in the Yemeni hinterland, and increased the frequency of cyclones, which cause destructive flash floods along the coasts. Water scarcity presents an even greater challenge: Yemen may soon exhaust its entire water supply. Attacks on Yemeni water supply networks powered by solar panels have only worsened this critical problem.

“All the reports and studies indicate that Yemen is one of the most water-poor countries in the world,” said Abdoul Razaz Saleh, a former Yemeni Water and Environment Minister.

Yemenis across the political spectrum managed to overcome their energy crisis and unite behind solar power with the support of the international community. This achievement can serve as inspiration for the kind of mass mobilization that Yemen needs to confront climate change as a whole.

“The international community can help Yemenis overcome water scarcity and climate change by deploying solar power on a large enough scale,” Elayah told LobeLog. “Yemen is rich in sun.”

Austin Bodetti studies the intersection of Islam, culture, and politics in Africa and Asia. He has conducted fieldwork in Bosnia, Indonesia, Iraq, Myanmar, Nicaragua, Oman, South Sudan, Thailand, and Uganda, and his research has appeared in The Daily Beast, USA Today, Vox, and Wired.

Interesting issue, but starting a real story with a lie doesn’t makes those lies become true as the rest of the story. Houthies are Yemeni’s with a long history of opposition and represent yemeYeme people more than any other fraction now. The rest are apparently interventions by the neighbors whom want to decide for their faith and rights. The alleged mysterious support from Iran, even if proven true doesn’t change these realities. Please consider telling the truth instead of whitewashing the crimes of KSA and UAE. However, evidently the Yemeni’s don’t have that money to offer to reporters for sake of the truth!

Couldn’t destroy your credebility with Yemeni people faster than this Mr. Bodetti. If that is your intention then you have chosen the right course. Equaling the actions of an aggressor with those who defend their country specially when we compare the actions is an unwise mistake. Do we have a cholera epidemic in Saudi Arabia? Are children dieing in Saudie Arabia due to hunger and mallnutrition caused by war? Yemenies, unlike Saudies, have not targeted weddings, bombed funerals and repeatedly striked hospitals, schools and medical facilities inside Saudie Arabia. No, the Saudies have done these war crimes with the weapons they get from U.S.