by Robert E. Hunter

Despite President Donald Trump’s lengthy agenda for his current trip to East Asia, it should in fact focus on one thing: what to do about North Korea and its rapidly developing nuclear capability.

Unless something totally unexpected happens in the next few months, the People’s Democratic Republic of Korea will soon be able to deliver nuclear weapons against some part of the continental United States. Never before has a country had this capacity, other than in circumstances in which the US has been confident that the threatening country’s leadership—the Soviet Union, China, and now perhaps Russia—had too much to lose in a war with the United States that could escalate to the use of nuclear weapons. Perhaps the DPRK leadership, at least notionally headed by 33-year-old Kim Jong Un, will be as rational as leaders in Moscow and Beijing have proved to be. But maybe not. And in the “maybe” is a risk of staggering proportions.

With Americans preoccupied with other matters, the North Korea issue has been back page for the last few weeks. The US media have focused far more on scandals, both foreign (the role of Russia in the 2016 presidential election) and domestic (sexual harassment). In foreign policy, far more media attention and government reaction has focused on what Iran might do—even though its potential for gaining nuclear weapons has been put off for at least a decade—than on the fast approaching direct threat to the United States from the Far East.

No doubt, if there is war between North Korea and any of its neighbors, the United States will be able to pulverize it, a point Washington has made repeatedly, backed up by displays of military force. Such rhetoric, as an unfortunate byproduct, plays into the hands of the North Korean leadership as showing its people that America is out to get them. But there would be a price for destroying North Korean military capacities, whether preemptively or if forced upon the United States by Pyongyang’s initiating major hostilities. Unless everyone has been getting the sums wrong for decades, North Korea has the capacity to destroy Seoul, the South Korean capital of more than 10 million people and only 35 miles from the dividing line between the two Korean states, using conventional artillery that the DPRK has deployed in great abundance. Thus, any conflict must be avoided if possible.

Trump’s Travels

Trump’s top officials and presumably the president himself must be aware of the clamor that will be let loose in this country when the North Koreans acquire the capacity to destroy one or more major US cities. Thus, on his trip to Asia, Trump will try to persuade China to do what it can to divert Kim Jong Un from his current course. If Trump also meets Russian President Vladimir Putin, he will also be asked to chime in, though Putin has virtually no influence in Pyongyang and little reason to be helpful to Washington.

China may want to try bringing Kim Jong Un and his clique under control. It should be in China’s interests to do so, for several reasons. These include its overall risk-averse nature, especially regarding potential conflicts near the homeland. Even though Beijing might up to a point be tempted to see the United States constrained in its East Asian activities by having to worry about a nuclear threat from the DPRK and thus more likely to accommodate China’s regional interests, it’s poor recompense for heightened risk, however slim, of cataclysm in East Asia. Even more important, China must be deeply worried that South Korea and/or Japan will cope with the North Korean nuclear capability by developing their own nuclear weapons.

Yet even if it’s in China’s interests to support the United States in the latter’s struggle to curtail the North Korean nuclear problem, that may not be possible, at least to the extent of reassuring the United States. Economic sanctions, China’s primary tool and much touted by Trump, rarely work and never when a regime sees either its own survival or the nation’s security to be at stake, as North Korea clearly does.

Indeed, North Korea is not about to give up all its nuclear military capability. It has only to look at what the United States has done to countries that have given up the capacity to develop these weapons—Libya, Iraq, and now Iran—to see that anything the US says by way of providing reassurances of non-hostile intent are worthless, at least as far as Kim and company are concerned. The North Koreans also no doubt value the prestige they have already gained by mastering history’s most menacing military technology and likely see their nuclear capabilities as a hedge in case China at some point develops its own ambitions on the Korean Peninsula.

In the absence of a miracle of diplomacy, the US will have only two serious responses. It can continue building ballistic missile defenses, though the capacity to blunt a determined North Korean missile attack directed toward the United States (or to any country in East Asia) cannot be guaranteed. No ballistic missile defense system can be foolproof, and only one nuclear-tipped missile “getting through” means a city lost. Furthermore, building a robust US missile defense system, though already underway, will take years to complete.

Dealing with Deterrence

The other serious response is to dust off the doctrines of nuclear deterrence that were effectively put on the shelf at the end of the Cold War when the balance of terror with the Soviet Union came to an end. These doctrines, which were elaborated over decades, are highly intricate, and their complexity is not easy to master. As an added problem, few of the senior-level people who had responsibility for managing the nuclear relationship with the Soviet Union (this author included) are still alive.

At heart, deterrence is a matter of psychology and of understanding the enemy’s mentality, including what it really values and the amount of destruction (if any) it is prepared to endure to achieve political objectives. Even if Kim and his colleagues understand that using nuclear weapons against the United States—or even of credibly threatening to do so—would mean Armageddon for North Korea, the risks of miscommunication are immense. Both the US and Soviet Union learned that in the Cold War, even with two highly sophisticated societies whose leaders, officials (military and civilian), scientists, and strategists were for most of the Cold War in regular contact with one another. By contrast, there are virtually no contacts between the United States and the DPRK, and it is not even clear that Pyongyang has people who understand the demands of deterrence.

It will also be highly difficult in US politics to accept the so-called Mutual Assured Destruction (MAD)—in which each side’s vulnerability to nuclear attack by the other, at least in theory, deters such attacks—that held sway with the Soviet Union and continues to do so today with Russia and China.

A further problem of great importance is that both South Korea and Japan are dead scared of the nuclear capabilities that North Korea already possesses. Under the Trump administration, they don’t have high confidence in US promises to defend them against North Korean aggression. (The technical term for such US security guarantees is “extended deterrence.”)

The US has extensive experience in this area. During the Cold War, which was in major part about the future of Europe, the United States was hard pressed throughout to convince its NATO allies that it would be prepared to commit suicide if need be in response to even a major Soviet conventional military attack on Western Europe. Indeed, “potential suicide” was the essence of US strategic commitments to Europe: that, in the event of serious Soviet conventional force aggression, at some point the US would initiate the use of nuclear weapons and that would very likely mean the end of civilization. Luckily, we all survived.

Convincing the Europeans—and especially West Germany, which was the likely frontline in a conventional war in Europe—that the US really meant what it said about the role of its nuclear arsenal required constant reassurance. Of central importance was to convince the West German government that it did not need its own nuclear weapons to deter the Soviet Union.

South Korean and Japanese Choices

Here is the most important parallel with the North Korea situation. Unlike the unqualified commitments the United States made toward Europe during the Cold War, Trump has raised profound doubts in both South Korea and Japan that he sees their security as synonymous with America’s in the face of aggression. The current Japanese government has been seeking to amend its US-imposed constitution, which Japan readily embraced for many reasons after World War II, to permit a more offensive posture for its military forces. With its stockpile of fissionable nuclear material, Japan may be only a “screwdriver’s turn away” from having nuclear weapons. South Korea can also be presumed to have the nuclear option and, given its greater vulnerability to North Korean aggression, even more reason than Japan to exercise it in the absence of complete confidence in US strategic guarantees.

Ironically, as with Germany and the Soviet Union, it will be harder to convince the Japanese and South Koreans that the United States would risk nuclear attack to protect them than it would be to convince North Korea of Washington’s willingness to employ the full force of US military might to counter DPRK aggression against one or both of these key Northeast Asian allies.

President Trump’s most important task on his Asian trip must therefore be to argue that he was “only musing” when he argued during the presidential campaign that maybe South Korea and Japan should assume more of the burden for their own security. Given the stakes involved for both countries and the uncertainties about where Trump’s heart really lies, that will be a daunting task. It also underscores the importance of enlisting China’s support in constraining North Korea far beyond what it has been willing or able to do so far.

Of course, the United States could try to revive diplomacy with Pyongyang. So far in this administration diplomacy has hardly been tried—save for a feeble attempt by Secretary of State Rex Tillerson, which earned him Trump’s tweeted rebuke, a terrible signal to Tokyo and Seoul and confirmation to Pyongyang that the United States seeks regime change despite Washington’s denials.

Thus even if China decides, in its own self-interest, on an full-court press on North Korea and succeeds at least in reducing the scope of its nuclear threat, the United States must refurbish its deterrence doctrine and consider all the problems entailed in mutual deterrence. It must also seek every means possible, direct and indirect, to open communications with Pyongyang to try reducing the risks of misunderstanding or misinterpretation. Finally it must pursue means, perhaps through China or Pakistan, to educate North Korean strategists and military leaders in Nuclear Deterrence 101.

In any event, the dangers will mount, as will public anxieties in the United States. One can only hope that Trump does not make the situation worse by what he says and tweets during his current trip to Asia.

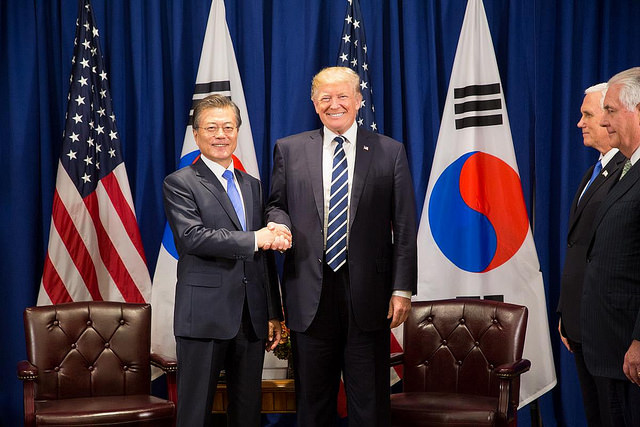

Photo: South Korean President Moon Jae-In and Donald Trump.

Excellent, Bob

More partisan opposition political policy agitating. Anti-Trump posture is evident. Unhelpful in recommendations. No weight given to military and diplomatic knowledge, experience, and leadership of present presidential appointments in State, Defense, or Intelligence. Disappointing and a reflection of views resident, and retained in “Deep State” bureaucracy, and at least questionable insofar of results from past performance.

Very fine analysis by the indefatigable Amb Hunter. My only question is whether, indeed, President Putin has little influence with the North Korean leadership. Seems to me he might have more than we imagine.

It’s the US that needs to be deterred on the Korea peninsula, where the US controls its ROK puppet and its military, conducting provocations including bomber flights and aggressive military operations, all outlawed by the 1953 Armistice Agreement. In fact the US military is not needed there and ought to be withdrawn. All this provocation is what drives DPRK to take necessary actions to deter the US against yet another attack and invasion against a foreign country.

Don Bacon as usual has a sensible comment. The author shows the terrible hubris of the USA, as if somehow it is correct in its belligerent attitude and the DPRK, which lives with the history of its complete destruction by the USA in the “Korean War” which has never officially ended. For decades the DPRK has tried to get a peace treaty and a firm commitment that the USA would not attack it, but except for a short and even successful try by Bill Clinton, this has never been even considered, and now Trump has of course made it worse by showing his behavior towards the JCPOA with Iran. Who can trust the USA?

The author seems to care only about the USA, which does NOT show any care for its allies (look at the actions against Russia, which hurt Europe, not the USA at all) and claims a great danger existed of the USSR invading Western Europe in the Cold War, while now the USA is surrounding and threatening Russia and China which are trading and making agreements, not invading.