bu Robert E. Hunter

The Trump administration’s recently issued National Security Strategy for 2017 has already sunk from public sight. Judged by its content, that is as it should be. As The New York Times reflected when the NSS was issued, both its tone and substance were in marked contrast to the remarks that President Donald made at its unveiling, which contained more of the sharp edges his foreign and domestic policies usually possess.

In any event, the annual NSS is a bastard document. Congress mandated its preparation and public issuance in the 1986 Goldwater-Nichols Act as a means for Capitol Hill to try getting a handle on the administration’s foreign and national security policy. But over the years, few if any of these documents have measured up to the task. Most important, the NSS is not operational: that is, it contains no decisions about foreign policy, defense, and the all-important appropriations to make them work. The Office of Management and Budget plays that role in its annual budget submissions to Congress. At the Pentagon, that role is played by the Quadrennial Defense Review (QDR), from which cascade progressively more granular documents that culminate in spending requests. The NSS itself has no practical effect.

The current National Security Strategy is also a misnomer. It contains little strategy in the form of the analysis of alternatives, the posing of choices, and the recognition of limits to America’s capacity to get its way in the world. Rather, it is an extended, 53-page wish list, a cobbling together of things that the various authors believe would be useful to do. As such, it inherently suffers from being the product of no overall guiding mind or hand-with-the-pen.

Even though this NSS is supposed to chart basic directions for the administration and hence the nation’s role in the world, President Trump did not likely read it, beyond at most a short precis, before he signed it. It is also doubtful that any cabinet-level official did so, with perhaps one exception: the secretary of defense, along with the Joint Chiefs of Staff, to whom the NSS awarded pride of place in America’s role in the world. Indeed, the document could very well have been written mostly by the four 3- and 4-star generals—Jim Mattis, H.R. McMasters, John Kelly, and Joseph Dunford—who dominate US foreign policy beneath the commander-in-chief. Obviously, as well, there could have been no serious, senior-level White House meetings, the normal practice of every previous administration, to bargain out differing viewpoints and to eliminate the internal contradictions with which this NSS is rife.

The Threats

Much public commentary has focused on the NSS’s negative comments about the ambitions and challenges—indeed threats—that China and Russia are posing to US primacy, with both aspiring “to project power worldwide:” China, probably, but Russia? It is still a second-rate power, whose importance has been inflated, to Russian President Vladimir Putin’s obvious delight, by US domestic political debate over its interference in the 2016 US presidential election.

Perhaps these two countries will be as permanently hostile to their neighbors and basic US interests as the NSS indicates. But surely there is little benefit in openly categorizing them, particularly China, in all-encompassing terms of almost across-the-board confrontation that thereby reduces chances for future cooperation. Even if permanent confrontation is to be expected, the NSS also lacks a serious road map for action to redress the imbalances that it posits. In the post-Cold War world, other countries will inevitably compete with the United States for a place in the sun and a major share of global influence, however unwelcome that is to a country used to getting its way most of the time. This new reality was always in the cards from the end of the Cold War onward. But to represent that as somehow at odds with historical experience or to be resisted at all costs, in matters both great and small, rather than to be accommodated as necessary while preserving genuine US interests, is peculiar at best and doomed to failure at worst.

North Korea, by contrast, has earned the epithets accorded it in the NSS. Iran, meanwhile, is singled out, along with the Islamic State, as the source of most of the evil in the Middle East and, indeed, is said to be sponsoring “terrorism around the world,” a bizarre stretch of the imagination. By contrast, Saudi Arabia, source and long-time supporter of most Islamist terrorism, only merits in the NSS a single, complimentary reference to its modernizing economy.

What’s Missing

There are also lacunae and absurdities. “Climate,” which must be accepted as one of the top national and global concerns, is mentioned only in regard to “countering an anti-growth energy agenda that is detrimental to U.S. economic and energy security interests.” Reference to the Paris Climate Accord, from which Trump withdrew the United States last June, is absent. Meanwhile, the NSS states that the United States “will work with allies and partners to achieve complete, verifiable, and irreversible denuclearization on the Korean Peninsula.” The inclusion of this statement, US policy for decades, can be excused as necessary rhetoric in an official document, but one must hope there is awareness in Washington that that goal can no longer be realistically achieved.

The NSS repeatedly calls on allies to support US objectives in the world, even where they do not see the world the way the Trump administration does. But then the document makes no reference to the needs and interests of allies, while US policies and presidential tweets regularly play down the role of key alliances and the views of major allies. The NSS asserts that “we develop policies that enable us to achieve our goals while our partners achieve theirs.” In practice, however, the administration regularly fails to do so, especially in Europe. Not surprisingly, the NSS makes no reference either to US withdrawal from the Trans-Pacific Partnership (TPP), thus ceding that ground to China, or its at-best ambivalence toward the Transatlantic Trade and Investment Partnership (TTIP). In both cases, the United States is at variance with key Western allies and trading partners. At the same time, the NSS is replete with charges of “excessive regulations and unfair foreign trade practices” by both friends and foes.

The same gap between pronouncement and reality is found in the NSS on “Advancing American Influence,” which properly and in places eloquently draws on US history as a nation and global leader. Yet the Trump administration has consistently violated its own prescriptions, such as “We treat people equally and value and uphold the rule of law” and “governments that fail to treat women equally do not allow their societies to reach their potential.”

The weakest part of the National Security Strategy is its cursory coverage of regional affairs, where the guts of policies should be discussed. This notably includes the Middle East, where the NSS advances no plan for reconciling contending elements, notably geopolitical competitions and age-old hatreds, beyond a wish list of desiderata. These include “We remain committed to helping facilitate a comprehensive peace agreement that is acceptable to both Israelis and Palestinians,” a throwaway line with no course of action attached other than to depreciate its significance for the region.

There is only a passing reference, by way of undercutting its value, to the Joint Comprehensive Plan of Action with Iran, which has prevented its acquiring nuclear weapons for the indefinite future. Yet the JCPOA is the most important US strategic success in the Middle East since the Camp David Accords and, just this week, was endorsed again by Britain and France, in a rare rebuke to the United States at the UN Security Council. And the conundrum in Syria, where continuing conflict brings together multiple strands of actors, policies, and contending interests, merits only a bromide: “We will seek a settlement to the Syrian civil war that sets the conditions for refugees to return home and build their lies in safety.” How, pray tell?

Military vs. Diplomacy

Worst of all, in terms of creating the basis for effective US action in the world is the gross imbalance between military challenges and responses on the one hand and non-military instruments and activities on the other. The report rightly notes that

Diplomacy is indispensable to identify and implement solutions to conflicts in unstable regionals of the world short of military involvement. It helps to galvanize allies for action and marshal the collective resources of like-minded national and organizations to address shared problems.

The NSS also rightly notes that “We will compete with all tools of national power to ensure that regions of the world are not dominated by one power,” a goal central to US grand strategy since 1917. Laudably, it emphasizes a major role for public diplomacy (which the Clinton administration trammeled when it regrettably abolished the United States Information Agency). Otherwise, the NSS gives short shrift to the instruments for conducting diplomacy, other than tools of economic diplomacy to benefit the US private sector abroad.

As a matter of practice rather than rhetoric, the Trump national security budget has called for a near-crippling 30% cut in resources for diplomacy and foreign aid. Meanwhile it is no secret in Washington that Secretary of State Rex Tillerson is odd-man-out in the central task of formulating US foreign and security policy. This contrasts with the report’s call for much greater spending on “military power that is second to none.” In justifying the further distortion of national-security priorities, the NSS ludicrously repeats Trump’s argument that “the United States dramatically cut the size of our military to the lowest levels since 1940”—a time when some Enfield rifles were still in service and none of today’s modern combat capabilities existed. In the NSS, the role of diplomacy is cited as talisman: a reference that had to be included, but then in practice subordinated to military primacy: “A strong military ensures that our diplomats are able to operate from a position of strength.”

When properly and usefully done, the National Security Strategy should be the basis for debate about the current and future nature of the world. It should assess America’s interests and potential actions in that world. And it should evaluate the instruments and methods, both integrated and balanced, to protect the nation and to advance purposes in the world that will work for the United States because they also work for others—a major leitmotif of the last seven decades. This NSS could also have been a useful antidote to most of the mainstream media’s “all anti-Trump, all-the-time” commentary by laying out a coherent strategy for the nation in the world. This document falls short in doing that.

Instead, in addition to being basically a listing of disconnected and often contradictory ideas, its overall theme is not just “America first” but also “America only.” It is not about the future integration of instruments of power and influence, but a top-heavy commitment to seeing military power as far and away uppermost. It thus validates President Barack Obama’s fear that, “Just because we have the best [military] hammer does not mean that every problem is a nail.”

The central message of NSS 2017 can be summarized simply: “Be afraid, be very afraid.” Yet anyone who believes that the world today is more dangerous for America and American security than it was from the 1940s to the end of the Cold War lacks both memory and historical perspective. This view also sees little or nothing positive to be achieved in the years ahead, certainly nothing that has the mark of past American successes, current moral and material strengths, or valid expectations for the future.

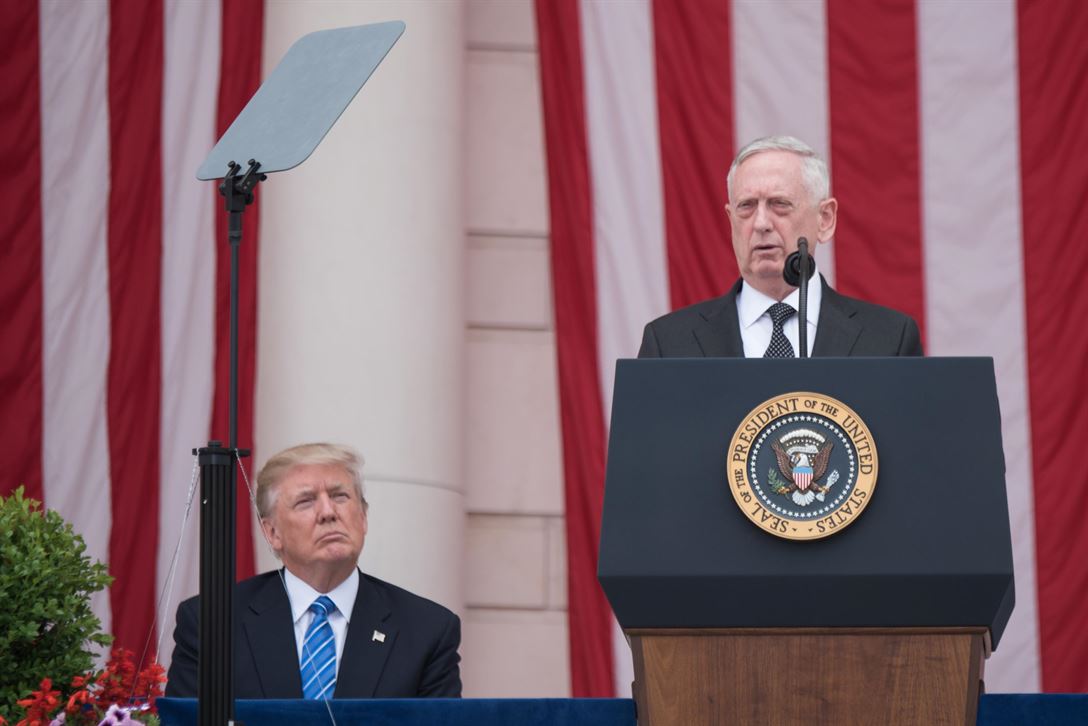

Photo: Donald Trump and James Mattis (courtesy U.S. Department of Defense).

“one must hope there is awareness in Washington that that goal [of Korea denuclearization] can no longer be realistically achieved.”

Caution is advised. The National Security Advisor, General H.R. McMaster, was selected primarily because he is supposedly a deep thinker and a successful author of a book as to why the US lost the Vietnam War, , , because Washington didn’t think big!

From an Amazon blurb on McMaster’s book, Dereliction of Duty: (quote) “victory” would require five years and 500,000 troops . . .McMaster doesn’t blithely exonerate the brass. They didn’t heed their own warnings and acquiesced in [SecDef] McNamara’s incrementalist policy, in the hope of eventually getting the huge force they diffidently advised would be needed to win.

McMaster won’t be diffident (shy), and Washington is increasing the size of the huge US Army. . . .It’s not to fight Canada or Mexico, either.

Also, regarding “This notably includes the Middle East, where the NSS advances no plan for reconciling contending elements, notably geopolitical competitions and age-old hatreds, . . .” That’s because the US war strategy is like diamonds, i.e. forever. There’s so much money in it, and no profits in peace. We must never believe that Washington doesn’t want instability and war, because they say that they want the opposite for one thing.

A good analysis by Robert Hunter.

A notable point to be added is the change in the Administration’s strategy regarding nuclear weapons. The December 2017 National Security Strategy proclaims: Nuclear weapons … are the foundation of our strategy to preserve peace and stability by deterring aggression against the United States, our allies and our partners. [They] are essential to prevent nuclear attack, non-nuclear strategic attacks, and large-scale conventional aggression.

In dramatic contrast, the 2015 National Security Strategy stated: We will advance the security of the United States, its citizens, and U.S. allies and partners by: … Striving for a world without nuclear weapons and ensuring nuclear materials do not fall into the hands of irresponsible states and violent non-state actors.