by Giorgio Cafiero and Bridgett Neff

Although the United States remains an extremely powerful force in the Middle East, the strategically flawed and disastrous invasion and occupation of Iraq in 2003, the financial crash of 2008, and the chaotic fallout of the 2011 Arab Spring uprisings all have served to accelerate America’s relative decline throughout the Arab world. As Abdulkhaleq Abdulla, a renowned Emirati political scientist, has written, the Obama administration’s reaction to the Syrian regime’s chemical attack in August 2013 in Ghouta increased most Arab Persian Gulf capitals’ concerns about their alliances with Washington.

Obama’s sudden U-turn on his own ultimatum on the use of chemical weapons by Bashar Al Assad…was a shattering experience and a huge letdown. It rattled the very foundations of the trusted [US-GCC] relationship. America failed miserably in Iraq and failed again in Syria. In both cases, America’s leadership was at stake and it took a huge tumble. From a Gulf perspective, the Syria mishandling is a watershed event and the relationship is not going to be the same anymore…There is no way on earth the Arab Gulf states can trust America as they used to during the past six decades.

Since Donald Trump entered the Oval Office in January 2017, the White House’s foreign policy decision-making has increasingly become transactional, unpredictable, unhinged, brash, and highly personalized. As a result, a host of states throughout the Middle East and North Africa (MENA) and beyond that depend on the United States as a security guarantor have grown even more nervous about remaining so reliant on Washington for defense. Although numerous Arab states historically allied with Washington began to look elsewhere for new partnerships beyond the United States prior to the Trump presidency, they have been doing so with a greater sense of urgency since the current administration took over the White House last year.

An Alternative Power to the US?

As Saudi Arabia and the UAE hedge their bets, Beijing is the world capital that can most credibly provide Riyadh and Abu Dhabi with a counter-balance to Washington’s role in the Arab world. For years, China has been pouring money into investment, development, and humanitarian assistance across the MENA region, culminating in a loan and aid package of $23 billion to Arab League members announced in July. China is already the region’s number one trading partner and imports more than half of its crude oil from Arab countries. This linkage between China and MENA states is likely to increase with Chinese President Xi Jinping’s ambitious One Belt, One Road initiative (OBOR), which envisions the Arab world as an international hub that links Asian, European, and African markets with, of course, China at the center of international trade.

The Saudi relationship with Beijing, in particular, is extremely important. In this century’s first decade, Saudi Arabia became China’s chief supplier of crude oil, and China replaced the United States as the kingdom’s top exporter partner. Sino-Emirati economic relations have also deepened significantly, with the UAE currently accounting for roughly one-third of all Chinese exports to Arab states and over one-fifth of total Sino-Arab trade.

The ascendancy of China against the backdrop of weakening American hegemony has led to a greater diffusion of power in an increasingly multipolar world, raising fundamental questions about Riyadh and Abu Dhabi’s twenty-first-century foreign policies. Given its energy consumption trends, China will become an even larger purchaser of Arab oil in the years ahead as North America becomes increasingly energy-independent from the Middle East. As such, Saudi and Emirati policymakers are questioning the extent to which their states should balance existing alliances with the United States with their strengthening ties with a rising China.

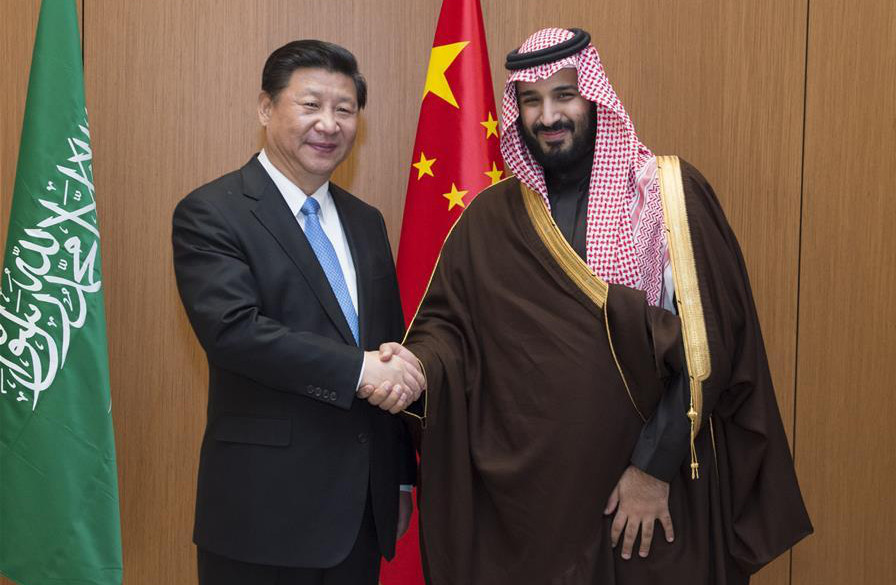

Beyond economics, there are many reasons why Beijing’s rise appeals to Saudi Arabia, the UAE, and other Arab states. China has shored up political ties in the region. President Xi, for instance, attempted to push Qatar and its Arab neighbors toward reconciliation amid the post-June 2017 Gulf Cooperation Council (GCC) crisis. Xi also made diplomatic visits to Egypt, Iran, Saudi Arabia, and the UAE. And the construction of China’s first overseas military base in Djibouti also clearly signals China’s push to increase its political capital.

At times of disagreement with the United States, a deeper partnership with China that further diversifies Riyadh and Abu Dhabi’s alliances affords the Saudis and Emiratis more leverage vis-à-vis Washington. Also, China avoids criticizing foreign governments’ human rights records. This “non-interference” foreign policy sits well with Saudi and Emirati officials whose rejection of certain forms of public criticism was recently underscored by the Saudi-Canada spat.

In turn, the Arab Persian Gulf monarchies have joined virtually all Middle Eastern regimes in remaining silent over the oppression in China’s Muslim-majority province of Xinjiang even as the Uighurs’ plight gains greater attention in the global press. This silence highlights the extent to which Saudi Arabia and other hydrocarbon-rich Arab states value their deepening relationships with China.

Limits of a China Partnership

Yet disagreements over a host of issues—from sanctions on Iran to the Syrian crisis—raise doubts over whether Saudi Arabia or the UAE will ever see China as their most favored world power. Ultimately, China’s willingness to collaborate with Iran, Qatar, and Syria underscores how Beijing’s efforts to maintain “neutrality” in the MENA region are challenged by certain Arab capitals, namely Riyadh and Abu Dhabi, pursuing maximalist foreign policies and initiating zero-sum conflicts.

Moreover, until China signals its willingness to shoulder the responsibility of protecting shipping lanes in the Gulf, rather than rely on the U.S. Navy to ensure such protection of international oil exports from the GCC states, the Arab Persian Gulf sheikdoms won’t fully pivot away to Beijing. As current allegiances stand, the United States remains the primary security guarantor for Saudi Arabia and other GCC states, providing the Saudi bloc with weapons, humanitarian aid, economic support, and a partner in the fight against terrorism. Despite declining American hegemony, China could not easily replace these provisions any time soon. Moreover, the Trump administration’s affinity for a hawkish Iran policy, immense military spending, and extensive political and economic connection to the Middle East suggests that alliance with the United States may be the more judicious partnership for the Saudis and Emiratis for the time being.

At this juncture, as tension between Washington and Beijing heats up, Riyadh and Abu Dhabi face difficult geopolitical dilemmas amid a shift toward a more multipolar world. Maintaining a prudent balance between Chinese and American interests in the region, recognizing the value of Chinese investment, and acknowledging the limits of partnering with Beijing would likely best serve Riyadh and Abu Dhabi’s interests.

For the time being, with Saudi and Emirati leaders seeing Iran as the top regional threat to their states’ interests, and with both Riyadh and Abu Dhabi having observed Beijing’s keenness to disrupt Washington’s efforts to isolate Tehran, it appears almost contradictory for either Arab Persian Gulf country to shift further toward Beijing. Nonetheless, the deepening of China’s relationships with the kingdom and the UAE, even without Beijing supporting their efforts to counter Iranian conduct in the Arab/Islamic world, will give Riyadh and Abu Dhabi greater autonomy, although neither capital is likely to take the immense risk of entirely disconnecting from the United States.

Bridgett Neff is an intern at Gulf State Analytics.

Or maybe better to think to a coexistence formula with Iran. Apparently Iran is not going to invade them against the arm dealers propaganda.

China is neither prepared nor willing to engage effectively in the complex politics of the region. China is nobody’s friend. It is the most amoral State in the world. It is also the most anti-religion. Interestingly, China also represents the domestic political model for the Saudis and UAE rather than the US – authoritarian regimes, not democracy. Fortunately there are 50,000 Saudi and 2,000 UAE students at US universities who will have little affinity for China going forward.

Saudi and china are combining efforts in Pakistan to develop oil city, which is massive development in region.

A small correction. Russia, not KSA, has been the top supplier of crude oil to China for the past two years. KSA is now in second place. Russia’s ESPO pipeline oil exports are set to increase as China attempts to diversify out of seaborne oil imports which constitute 80% of oil imports. In addition, part of Russia’s oil exports are in exchange for earlier Chinese loans.