by James M. Dorsey

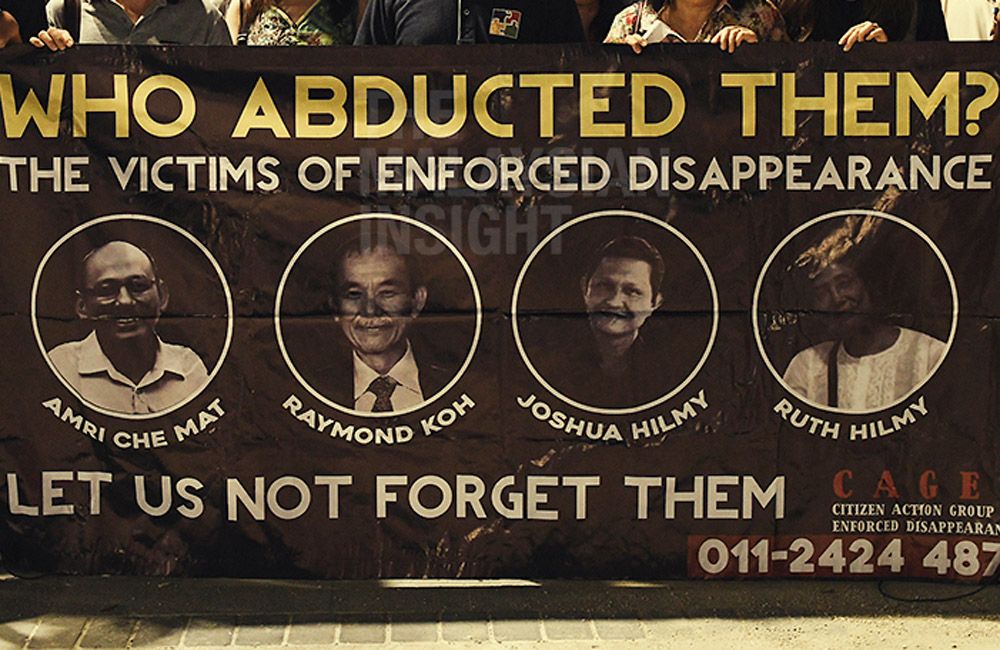

Allegedly kidnapped, forty-three-year old Malaysian activist Amri Che Mat, a foreign exchange trader and mountain climber, has not been heard of since he went missing in November 2016.

An inquiry into his disappearance coupled with an assertion by Mohd Asri Zainul Abidin, the mufti of the state of Perlis, that Malaysia’s miniscule Shiite Muslim community constitutes a national security threat are but the latest incidents that have raised concerns about the impact of Saudi-inspired ultra-conservative strands of Islam.

Shiites in Malaysia, a country of 31 million, are believed to number 40,000. Shiism was banned in 1996, but Shiites are allowed to worship privately.

Amri’s black four-wheel-drive was found the night of his disappearance near a construction site with its windows smashed, a 55-minute drive from his home in Kangar, Perlis’ capital. Witnesses said his car was blocked by five vehicles when he was snatched close to his house.

Accused of adhering to Shiism, Perlis’ Islamic Religious Department, advised the state’s schools two months prior to Amri’s disappearance not to participate in programs managed by Perlis Hope, the charity co-founded by the activist. Perlis Hope was donating school bags and uniforms.

The charity, in testimony this month to Malaysia’s Human Rights Commission that is investigating the vanishing of Amri and three other activists, denied that it was associated with any one religious grouping.

Asri, the mufti, fuelled debate about creeping influence in Malaysia of ultra-conservatism with assertions earlier this week that Amri was a Shia, who practised mut’ah, a temporary marriage contract under Shiite religious law.

The mufti accompanied police who came to their house in 2015, according to Amri’s wife, Norhayati Ariffin, to question the activist about his Shiism, a strand of Islam that Asri denounces as deviant.

Speaking this week, Asri said Amri’s home was decorated with pictures of Shia imams. “The surroundings were similar to a Shia mosque in Iran,” he said.

The mufti denied assertions by Ms. Ariffin in testimony to the commission that his department may have been involved in Amri’s disappearance. “Maybe her husband has gone off somewhere. Maybe he has gone to Iran. Maybe he has gone to practise mut’ah in Thailand. How should I know?” Asri said.

The mufti asserted that the spread of Shiism in Perlis and neighbouring Thailand “could threaten national security.” He asserted that Perlis Hope was possibly seeking to establish a theocracy.

The disappearance and Asri’s remarks follow a string of events and government measures that have sparked renewed debate about what critics have dubbed the country’s Arabization. Malaysia has long been a target of a long-standing, well-funded Saudi public diplomacy campaign that propagates Sunni Muslim ultra-conservatism as an anti-dote to Iranian revolutionary zeal and Shiite ideology.

Saudi influence was further spotlighted by a scandal surrounding Malaysia’s state development fund 1MDB sparked by revelations that $700 million had wound up in Prime Minister Najib Razak’s bank account in 2013. Najib said it was a donation from the Saudi ruling family, rebutting allegations it was money siphoned from the fund he had founded and overseen. Malaysia’s attorney-general cleared him of any wrongdoing.

On a visit to Malaysia a year ago, Saudi King Salman inked agreements involving $10 billion of investment in Malaysia and the building of a King Salman Centre for International Peace to bring together Islamic scholars and intelligence agencies in an effort to counter extremist interpretations of Islam.

The centre would work as resource partners with the Saudi-financed Islamic Science University of Malaysia, and the Muslim World League, a Saudi-funded non-governmental organization that for decades served as a vehicle for global propagation of ultra-conservatism.

Saudi Arabia’s relationship with Malaysia has also been thrust into the limelight by Najib’s increased emphasis on Islam and close ties to the kingdom.

Malaysian defense minister Hishammuddin Hussein said this week that Malaysian forces would remain in Saudi Arabia ” for the sole purpose of providing humanitarian assistance and possibly contribute to rebuilding efforts in Yemen if required.” Malaysia had earlier refused to send troops to fight in the kingdom’s ill-fated military effort to counter Iranian-backed Houthi rebels in Yemen.

The government recently backed a parliamentary bill that would allow the shariah courts wider criminal jurisdiction over Muslims in the state of Kelantan. Malaysian authorities last year banned two beer festivals against a backdrop of mounting hostility towards Shiites, atheist and gays.

Malaysia has also given refuge to Zakir Naik, a militant Indian Islamic scholar who has been banned from entering Singapore and Britain because of his advocacy of the death penalty for homosexuals and those who abandon Islam.

Malaysia’s sultans, in a rare warning cautioned last October that Malaysia’s stability was at risk from political Islam after attempts by two laundromats to service Muslims only were blocked by local authorities.

Sultan Ibrahim Sultan Iskandar, the sovereign of the Malaysian state of Johor, in perhaps Malaysia’s starkest confrontation of Saudi-inspired ultra-conservatism last year denounced practices of Wahhabism and Salafism by calling on Malaysians to uphold their country’s culture and not imitate Arabs. The sultan decried what he described as creeping Arabization of the Malay language by insisting on using Malay language references to religious practices and Muslim holidays rather than Arabic ones.

“If there are some of you who wish to be an Arab and practise Arab culture, and do not wish to follow our Malay customs and traditions, that is up to you. I also welcome you to live in Saudi Arabia. That is your right, but I believe there are Malays who are proud of the Malay culture. At least I am real and not a hypocrite and the people of Johor know who their ruler is,” the sultan said.

James M. Dorsey is a senior fellow at the S. Rajaratnam School of International Studies, co-director of the University of Würzburg’s Institute for Fan Culture, and co-host of the New Books in Middle Eastern Studies podcast. James is the author of The Turbulent World of Middle East Soccer blog, a book with the same title as well as Comparative Political Transitions between Southeast Asia and the Middle East and North Africa, co-authored with Dr. Teresita Cruz-Del Rosario, Shifting Sands, Essays on Sports and Politics in the Middle East and North Africa, and the forthcoming China and the Middle East: Venturing into the Maelstrom. Reprinted, with permission, from The Turbulent World of Middle East Soccer blog.