by Jalil Bayat

The Iranian government began an unprecedented fight against economic corruption over a year ago. News of trials in corruption cases is broadcast on Iranian state television and other media outlets every day and officials, particularly in the judiciary, stress the need to tackle economic corruption on all fronts.

Previously, anti-corruption efforts in Iran had been limited to a few isolated cases, such as those of Shahram Jazayeri, Mahafarid Amir-Khosravi, and Babak Zanjani. Now, it seems that Iranian authorities are fighting corruption relentlessly and comprehensively, even in the cases of President Hassan Rouhani’s brother, the daughter of a former minister in Rouhani’s cabinet, and even high-ranking officials working in the office of the former head of the Iranian judiciary and current chair of the Expediency Council, Sadeq Larijani. The extent of the fight against economic corruption is such that a special complex to deal with such cases has been set up in Tehran Province’s justice department.

Although human rights groups such as Amnesty International have expressed concern about the special courts, how to handle crimes and especially the manner in which hanging sentences are issued for financial offenders, Iran appears to be pursuing three goals in its fight against economic corruption:

Addressing Public Discontent and Neutralizing U.S. Propaganda

A series of protests across multiple Iranian cities in December 2017 highlighted public anger over official corruption. Demonstrators, upset over Iran’s continued economic struggles chanted slogans calling for the prosecution of corrupt officials. In establishing courts to hear corruption cases, the Iranian government is attempting to show its resolve to deal with the issue and thereby address public grievances. There are signs it may be working—Iranian Interior Minister Abdolreza Rahmani Fazli said in August that protests declined by 38 percent over the first five months of the Iranian year (which begins in March), as compared with the same period one year ago.

The Iranian government is also trying to undermine the efforts of the U.S. government and exiled opposition groups to use these protests as part of their regime change efforts. The Trump administration has been close to many exiled Iranian opposition groups, especially the Mojahedin-e Khalq Organization or MEK, through people such as Trump lawyer Rudy Giuliani and former National Security Advisor John Bolton. The MEK and royalists (supporters of the Pahlavi Dynasty) have been making allegations about corruption within the Islamic Republic for years.

The Trump administration itself has also used corruption as a rhetorical weapon against Tehran. Secretary of State Mike Pompeo, and U.S. Special Representative for Iran Brian Hook have claimed time and again that Iran’s leaders are squandering the Iranian people’s money or using it to finance their aggressive regional policies. In emphasizing this issue while simultaneously trying to cripple the Iranian economy through its “maximum pressure” sanctions program, the U.S. intends to lay the groundwork for popular unrest and the collapse of the Iranian regime from within. Hence, publicity by the U.S. administration and exiled Iranian oppositions against the Iranian regime intensified after the December 2017 protests. In publicly taking action to address corruption, the Iranian aim is to neutralize U.S. propaganda and reduce public discontent at the same time.

Financing Part of Government Spending

Oil revenue is the Iranian government’s most significant income source and U.S. oil sanctions have drastically reduced Iran’s foreign exchange earnings. In past years, this revenue was more than sufficient to fund the Iranian government and there were no concerns about combating embezzlement and economic corruption. But current constraints have led Iran to economize in spending and fight corruption to finance part of its budget.

According to the judicial laws of the country, economic offenders in both the private and public sectors are sentenced to jail and fined in cash payable to the state fund. The number and amount of embezzlement and economic corruption in Iran is so high that the total sum of financial penalties can be very significant and cover part of government spending.

Since the drop in oil exports means fewer dollars, this is a good incentive to trade in national currencies. Those convicted of corruption are fined. In addition to domestic spending, the government can use the money in foreign trade (in national currency).

So, Iran is trying to reduce its dependence on the dollar and has begun trading with several countries without using this currency. The Governor of the Central Bank of Iran (CBI) announced recently that all Iranian trade with Russia and 30-40 percent of trade with Turkey will take place with national currencies.

Therefore, Iran is trying to finance part of its budget by tackling economic corruption and tax evasion, expanding tourism, reducing dependence on oil revenues, and promote trading in national currencies.

Leadership Succession

Iran’s Supreme Leader, Ayatollah Ali Khamenei, is 80 years old and talks about his succession have been ongoing in the political circles of Iran in recent years. Presently, two people seem to have the most potential to succeed him.

The first person is President Hassan Rouhani, who has attempted to de-escalate tensions and expand economic ties with the West. He succeeded on this path to some extent by signing the Joint Comprehensive Plan of Action (JCPOA) nuclear deal with China, France, Germany, Russia, the United Kingdom, and the United States in 2015. But the economic consequences of Donald Trump’s withdrawal from the deal, coupled with resistance from Rouhani’s domestic opponents, means that he has now lost not only his popularity, but is also under pressure from both sides of the political spectrum.

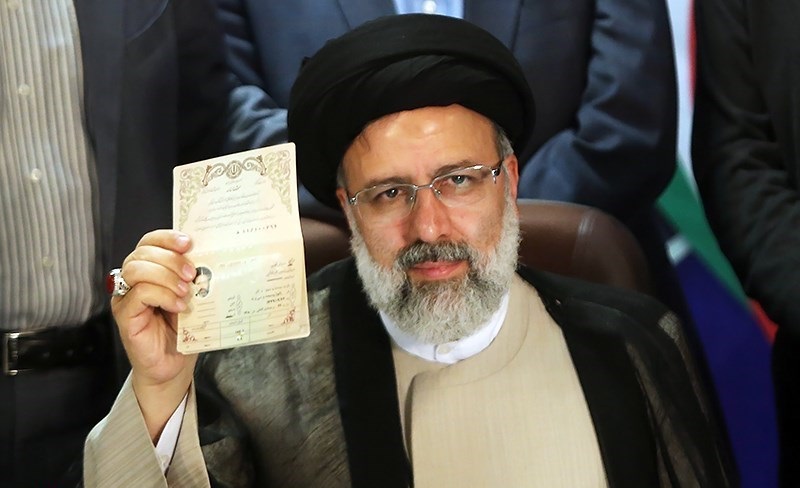

The second person is Ebrahim Raisi, currently the Head of the Judiciary, who gained fame during his 2017 presidential campaign. He is active in the fundamentalist camp. Running as a conservative challenger in the 2017 election, Raisi won 38.3 percent of the vote but lost to Rouhani, who won 57 percent of the vote. This defeat diminished the possibility of Raisi’s election as the future Supreme Leader of Iran. According to the Iranian constitution, the Supreme Leader is elected by the Assembly of Experts, yet the acceptance of a future leader by the people is necessary.

But Khamenei’s decision to appoint Raisi as the head of the judiciary in March 2019, and recent political setbacks for Rouhani, have put Raisi back in the game. His seriousness in fighting economic corruption, even targeting corrupt judges and agents within the judiciary, has gained him support not only in the independent camp but also among reformists.

As such, the anti-corruption campaign seems to be a good way to popularize Raisi and increase his chances of succeeding Khamenei. In this respect, the fundamentalist faction—which holds many positions of power in Iran—is trying to use the fight against economic corruption to lay the groundwork for electing one of its key members as Iran’s future Supreme Leader.

Is the Crackdown Targeting Reformists?

Certain media outlets in the West believe that, given the large number of reformists being arrested in the anti-corruption campaign as compared to fundamentalists, the fight against economic corruption in Iran is aimed at weakening reformers and moderates. But this proposition is not accurate.

Corruption in Iran is linked to political power. Therefore, whichever of Iran’s two main political factions—fundamentalist or moderate-reformist—takes over the executive branch, corruption among the members of that faction increases. At the end of former President Mahmoud Ahmadinejad’s term in office, for instance, his first vice president, Mohammad-Reza Rahimi, and his Vice President for Executive Affairs, Hamid Baghaei, were imprisoned for economic corruption and embezzlement. Such corruption reached an all-time high during his tenure in office.

Hence, if there are more detainees among the reformists at this time, it is because they are currently in charge of the executive branch. Nevertheless, fundamentalists such as the Minister of Welfare and Social Security under Ahmadinejad, Parviz Kazemi; former Deputy Chief Executive of the Judiciary Akbar Tabari; the deputy to former Tehran Mayor Mohammad-Bagher Ghalibaf, Issa Sharifi; and two fundamentalist MPs, Mohammad Azizi and Fereydoun Ahmadi, are also among the detainees.

As such, it seems that the current anti-corruption campaign is being waged with seriousness, although to be sure some influential figures continue to remain immune.

Jalil Bayat is a PhD candidate in international relations at Tarbiat Modares University in Tehran.

Anti corruption efforts in Iran are many years behind times. The system has so many holes in it that the inept past and present governments are either involved in these corruptions and they don’t want to admit to it or don’t know about it at all since it pops up and it surprises them everyday. Of course they have no idea how to deal with the corruption cancer! The corruption cancer has metastasized and this recent efforts, although commendable, but are too little and too late!

When corruption becomes a ‘norm’ and epidemic and then an unofficial ‘legal norm’ practised across the country then it becomes an integral part of the culture, then it is hard to eradicate it, and the officials depending on their tactics take it for granted that since without the ‘legal corruption’ and ‘bribery’ the institutions cannot properly function, just like an engine that would not work without lubrication, the highest governmental offices too have to accept the prevalent culture in order to function as ‘normal’!

And when big dealings are unravelled, new showmen appear on ‘anti-corruption’ stage and it gets hilarious when they begin their own blind man’s bluff game! The players who have known one another too well for too long now pretend otherwise to amuse themselves and their audiences.

After 40 years of ‘revolutionary’ corruption, ‘blessed’ mismanagement and shamelessly cheating with impunity in the name of Islam and filling their pockets and saving them inside and outside the country, now by pointing at the tip of the iceberg our corrupt officials and their judicial system embarking on their ‘blind man’s bluff’ might end up putting their whole shambles system on trial!

Anton Chekov, Gogol and Mikhail Bulgakov would have found our anti-corruption campaign too satirical to be true!

The funniest part of this propaganda piece by its “Ph.D. candidate” author (who seems to be trying to please Raisi, especially if he becomes the next brutally imposed “Supreme Leader” of Iran) is the following gem of ANTI-ISLAMIC falsehood:

“[It] seems that the current anti-corruption campaign is being waged without discrimination…”

It is really “funny” because almost NONE of the EXTREMELY corrupt and brutal minions of Khamenei (and the Revolutionary Guards and Basij) have even been questioned, let alone arrested, despite the hundreds of billions of dollars they have stolen/extorted, so far, and the author of the essay knows this of course, but it seems more “beneficial” to him to LIE.

Ayatollahs by definition want to be against any world system. The world thinks that they are financially self serving and mad. The international Ayatollah sanctions, will force Ayatollahs, to cling on to their dwindling assets, and compete for what little money they have, amongst themselves with anger and hate.

The Ayatollahs will accuse each other of corruption, as they will impose more sanctions on innocent non-violent secular Iranians. In the end, desperate Ayatollahs will face self-destruction and look for a fight. But they will only fight their own kind.

Iranians are aware, and watch them with vigilance, and calm, not falling for their anger, but instead preserving our ancient civilization in peace and love of Ahuramazda.

Indira Gandhi said:

One must beware of ministers who can do nothing without money, and those who want to do everything with money.

Come to think of it, most of us Iranians are predisposed to bribery and corruption for many decades. We love to grease the wheels in order to to expedite everything in every day life. There are some arguments if this started during Safavid dynasty and has become a cultural issue until today for which a new name has to be invented! When an average person has to pay someone to obtain a birth certificate for his/her child or bribe an asshole with slippers instead of having shoes on to renew his/her passport the whole society is on a slippery road and skiing down the slopes! It is so sad and angering situation! Peace be with the good people of Iran!