by Peter Jenkins

In connection with President Bashar al-Assad’s planned visit to North Korea, David Sanger and Mark Landler wrote on June 4 for The New York Times:

The last time Mr. Assad did business with the Kim family, the result was one of the most brazen cases of proliferation in history: North Korean engineers built a replica of their main nuclear reactor in the Syrian desert. It was the beginnings of a nuclear program that ended in fiery ruins in September 2007, when the building was destroyed in a secret Israeli bombing run.

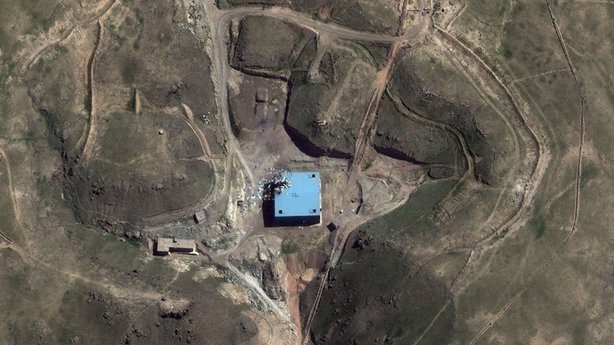

Sanger and Landler must have imagined that there was a solid basis for what they wrote, since on March 21 Haaretz published a long story about Israeli derring-do under the headline “No Longer a Secret: How Israel Destroyed Syria’s Nuclear Reactor.” Israel’s prime minister subsequently confirmed the essence of the story: Israeli jets destroyed a Syrian reactor when they struck a building at al-Kibar, near Deir al-Zour in early September 2007.

Whether the building destroyed in that Israeli raid housed a nuclear reactor is less certain than these Israeli claims imply.

In May 2011, at the end of a three-year investigation that included access to the al-Kibar site in June 2008 and the collection there of soil samples, the International Atomic Energy Agency (IAEA) was unable to state with certainty that a nuclear reactor had been destroyed. Instead they assessed it “very likely that the building destroyed at the site was a nuclear reactor.”

IAEA governors decided that this justified their finding that “Syria’s undeclared construction of a nuclear reactor” amounted to non-compliance with Syria’s IAEA safeguards obligations. But information which has come to light since suggests ample grounds to doubt whether the finding was accurate.

According to the March 2018 Haaretz report, Israeli identification of al-Kibar as the site of a Syrian reactor took place in March 2007. The basis for it was material taken from the personal computer of the head of Syria’s Atomic Energy Commission. The material led Israeli intelligence analysts to deduce that a reactor was under construction at al-Kibar and nearing completion, and that it was modelled on a North Korean reactor located at Yongbyon.

If the “reactor” were nearing completion and of the Yongbyon type, reactor-grade graphite should have been present in large quantities in the soil samples that IAEA inspectors collected in June 2008, even though by then the site had been cleared of all traces of the destroyed building. Reactor-grade graphite is an essential component of the cores of gas-cooled, graphite-moderated reactors (GCGMR) like the one at Yongbyon. The bombing of the “reactor” would have dispersed particles far and wide.

But the IAEA was unable to certify the presence of reactor–grade graphite in the soil samples. In its May 2011 report, the agency merely implied that graphite particles collected at the site might or might not have been reactor-grade: “the graphite particles were too small to permit an analysis of the purity compared to that normally required for use in a reactor.” This conclusion should cast doubt on the hypothesis that a GCGMR was under construction at al-Kibar, given modern analytical capabilities, in the view of two nuclear engineers that Gareth Porter interviewed for a piece in Consortium News.

A second reason to doubt the North Korean reactor theory is the IAEA’s suggestion that the “reactor” building also housed a spent fuel cooling pond. In the view of Yousry Abushady, an IAEA inspector for 23 years and a GCGMR expert interviewed by Porter, this is highly improbable. At Yongbyon, and everywhere else in the world where GCGMRs have been built, the cooling pond is located in a separate building, away from the reactor building, for safety reasons.

The dimensions of the supposed reactor building are also an issue. It’s not just the length and breadth that are different: 40m by 40m at al-Kibar, and 47m by 47m at Yongbyon, according to Haaretz. It’s also the height. Abushady, who visited the Yongbyon site as an inspector on several occasions and who studied photographs of the al-Kibar “reactor” building released by the CIA in May 2008, estimates that the latter was less than half the height of the Yongbyon reactor building. It was thus nowhere near high enough to house a Yongbyon-type reactor (let alone long enough to house a cooling pond in addition to the reactor).

A further question concerns anthropogenic natural uranium particles. In May 2011, the IAEA reported that it had found such particles. Characterizing them as evidence of “nuclear-related activities at the site,” the agency implied that their presence supported the reactor hypothesis. But for that judgment to be credible such particles should have been present in the IAEA’s soil samples. Instead, the June 2008 soil samples were devoid of anthropogenic natural uranium particles, according to Robert Kelley, a US-trained engineer and ex-IAEA inspector whom Porter interviewed and in whom a member of the June 2008 Syria inspection team confided. The particles came, rather, from a “changing room” at al-Kibar.

A fifth issue is the uncertainty that surrounds how the “reactor” would have been fueled. The North Koreans “froze” their GCGMR fuel fabrication plant at Yongbyon in 1994. In 2011, the IAEA described the plant as having been in poor condition in 1994 and having deteriorated further during the “freeze.” In Playing to the Edge, published in 2016, Michael Hayden, CIA director from 2006 to 2009, discloses that the CIA searched for a Syrian fuel fabrication plant without success.

These are not the only grounds to question Israeli claims about their September 2007 exploit. Others can be found in Porter’s November 2017 Consortium News piece. But these five are reason enough to doubt whether what Israel destroyed in its September 2007 raid was a replica of a North Korean reactor.

One last point merits a mention. Porter quotes from Playing to the Edge to describe how Hayden decided to release supposed evidence of North Korean reactor collaboration with Syria to sabotage a US nuclear deal with North Korea that appeared to be in the offing, since he (and Vice President Dick Cheney) were opposed to it. Does that episode explain, by analogy, why The New York Times chose to reminded its readers of the Korea-Syria reactor story eight days before Donald Trump is due to meet Kim Jong Un in Singapore?

The vessel head is in-place in the picture by the CIA that claims to be this “reactor” at this place. That means the graphite MUST already be inside if there is any graphite. The IAEA reports finding a few particles of carbon based material and claims that the particles are too small to determine their purity. What they leave out is that approximately half the particles have the morphology of coal, not processed graphite and Al Kibar is in a region of coal-mining and coal shipment. Don’t these people do any analysis? When data is inconvenient do they just leave it out? This is purely political posturing and has no relation to the scientific method. The IAEA Board of Governors should demand an independent investigation of this sorry exercise including the provenance of all the samples taken legally and otherwise by its inspectors.

Very interesting to know after many years the truth.

The article is like a drop of truth in a rain of lies, but the diamond of truth will shine while the lies will find the way and follow their lords to nowhere!

Always a diplomat, Peter Jenkins slides the punch line of his piece in the last paragraph. And he leaves it to readers to speculate on why The New York Times would want to ‘sabotage a US nuclear deal with North Korea’. Maybe the editor-in-chief just decided they should follow up the news of a possible Assad visit to DPRK, and published what his ‘investigative journalists’ came up with in a hurry. Isn’t it more likely that the DPRK-Syrian collaboration on missiles would be involved? This whole adventure, with Gareth Porter and Robert Kelley, certainly reminds one that unconfirmed conspiracy theories abound in that part of the world.

Rather than worry about conspiracy theories one must question why the IAEA is incapable of independent analytical capabilities. Physics and metallurgy are immutable here. Depleted uranium and natural uranium are equally useful in conventional munitions so making a call to report Syria to the security council on incompetent science does not bode well for IAEA. IAEA cherry picks open source data they like and suppress that with does not fit the predetermined conclusion. They selectively fail to report key pieces of information such as the lack of barite, the presence of coal instead of graphite and the unconventional collection of samples by rogue inspectors. We may be on the cusp of serious inspections and analysis in DPRK if Trump and Kim reach an agreement. If the verification of the nuclear agreements is not given to IAEA, but instead to teams formed for the purpose, as in 1991 Iraq, IAEA needs to take a long look in the mirror.