by Omer Taspinar

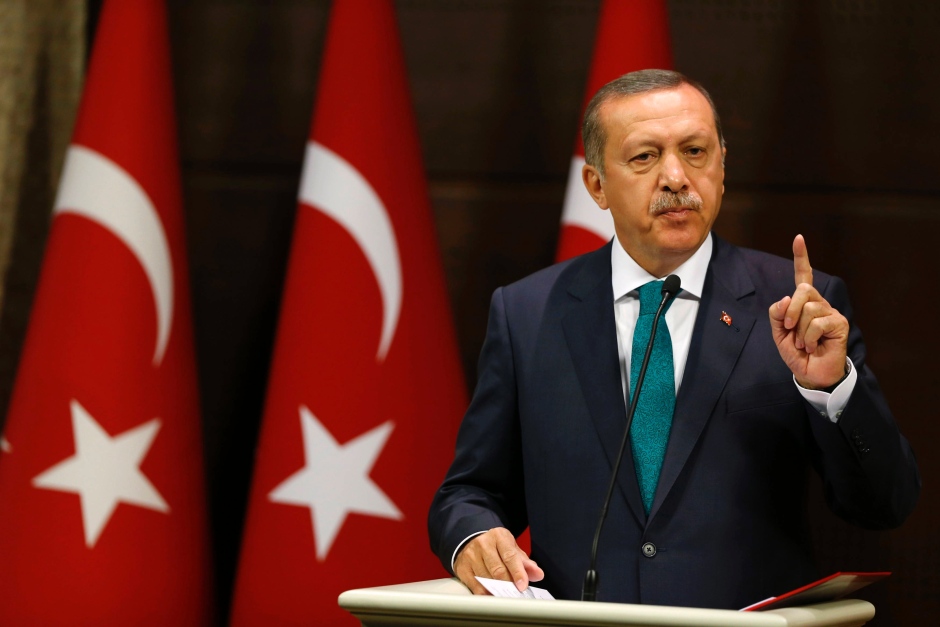

Western media has an understandable tendency to see Turkish President Recep Tayyip Erdogan as an incurable Islamist who is determined to overhaul the secularist legacy of Ataturk. Many Western policymakers, analysts, and scholars equate the notion of a Turkish divergence from the West — or the fear of “losing Turkey” — with the idea of an Islamic revival. This is an understandable fallacy. After all, a political party with Islamic roots has won five consecutive elections in a country where the population is 99 percent Muslim.

Moreover, until recently this secularist-Islamist dichotomy played an important role in the societal polarization of the country. Yet, since 2013, the power struggle between the AKP and followers of Fetullah Gulen, culminating with the failed coup this summer, has changed the picture. Secularism had nothing to do with this Islamic fratricide. Similarly, secularism versus Islam has no relevance for the bloody confrontation between Kurdish and Turkish nationalism, the most existential of problems facing the future of the nation-state in Turkey. It is time to admit that what we are witnessing in Erdogan’s “New” Turkey is the rise not of political Islam but of a much more powerful and potentially more lethal force: nationalism.

The same alarmist dynamics are increasingly visible in Turkish foreign policy. Although the importance of political Islam in Erdogan’s agenda should not be fully dismissed, the real threat to Turkey’s Western and democratic orientation today is no longer Islamization but growing nationalism and frustration with the United States and Europe. The situation has become much more alarming lately. The failed coup has instigated an ultra-nationalist realignment in Turkish politics that threatens to take the country in a proto-fascist direction. In essence, what is rapidly emerging in today’s Turkey is a marriage between the AKP, the ultra-nationalist MHP (Nationalist Peoples Party) and the Turkish military–or what is left of it, since more than a third of its flag officers have been discharged or detained since the mutiny.

Under such circumstances, a more nuanced reading of Turkey’s strategic direction requires going beyond Islamist-secularist clichés by looking at the intersection of the three main strategic visions in Turkish foreign policy: Neo-Ottomanism; Kemalism and Turkish Gaullism. The common denominator in all these trends is the primacy of Turkish nationalism. While Kemalism and neo-Ottomanism are fairly well known in the international political lexicon, Turkish Gaullism is a conceptual construct I have been using to describe their nationalist convergence.

Despite the important differences between the “secularist nationalism” of Kemalism and the ”religious nationalism” of neo-Ottomanism (seeking to project soft power in formerly Ottoman territories) both strategic visions are strongly attached to Turkish national interests. Neo-Ottomanism and, especially, the “Eurasianist” wing of Kemalism (well-represented among officers who now have upward mobility in the army) are in favor of regional strategic alliances to boost Turkish leverage against Western partners in the transatlantic alliance. At the end of the day, both neo-Ottomanism and Kemalism share a state-centric view of the world with the primacy of Turkish national interests. In that sense, both ideologies share Turkish nationalism as a common denominator.

If current trends continue, what we will see emerging in Turkey is not an Islamist foreign policy but a much more nationalist, defiant, independent and self-centered strategic orientation — in short, a Turkish variant of “Gaullism.” As in the case of Charles de Gaulle’s anti-American and anti-NATO policies in the 1960s, a Gaullist Turkey may in the long run question Ankara’s membership within the military structure of NATO or the logic of waiting for the elusive EU membership. In search of full independence, full sovereignty, strategic leverage and, most importantly, “national prestige, glory and grandeur,” a Gaullist Turkey may opt for its own “force de frappe” — a nuclear deterrent — and its own “Realpolitik” with countries such as Russia, China, and India.

One should not underestimate the emergence of a “New Turkey” that transcends the Islamic-secular divide, because both the Turkish military’s Kemalism and the AKP’s neo-Ottomanism share the primacy of national interests against Western influence. Turkey’s current military offensive in northern Syria, the growing anti-Americanism at home, the rapprochement with Russian and Iran, the frustration with the EU over visa liberalization, and the war against the PKK are all factors that will contribute to the growth of Turkish Gaullism.

Omer Taspinar is a nonresident senior fellow in the Center on 21st Century Security and Intelligence and an expert on Turkey, the European Union, Muslims in Europe, political Islam, the Middle East, and Kurdish nationalism. He is a professor at the National War College and an adjunct professor at Johns Hopkins University’s School of Advanced International Studies.

The AKP popularity has three pillars. First the idolatry toward of Erdogan as the father of the new prosperous Turkey. Second Turkey surprisingly successful economy. Third the revival of a nationalistic Islam.

Should any of this pillars weakens the whole structure may collapse.

While the nationalistic pillar is very strong and developing fast, the economy is highly dependent and the EU and the USA.

Also Erdogan can’t stay in power much longer.

Therefore it is doubtful that Turkey will become ‘independent’ of the EU and the USA as the author claims. It is also doubtful that Erdogan will remain in power for long. Therefore despite what the author writes, the only resilient pillar is the Islamo-Ethnico nationalism. When abused as it is now, its direct effects will be to divide the country further and may destroy its illusory unity.

Erdogan thinks that he can enslave the ethnical minorities by attacking them militarily. He is wrong, as he has been wrong in all the decisions in foreign policy that he took in the region in the last 5 years .

Unless another leader takes over Erdogan fast enough, Turkey is on a deadly path.

MHP is not Nationalist Peoples Party, but Nationalist Movement Party. Though you can not translate even name of a party existing in your own country, how can we speak of BEING AN EXPERT ON TURKEY?