by Jim Lobe and Joe Hitchon

WASHINGTON, May 18 2013 (IPS) – A nuclear-armed Iran would not pose a fundamental threat to the United States and its regional allies like Israel and the Gulf Arab monarchies, according to a new report released here Friday by the Rand Corporation.

Entitled “Iran After the Bomb: How Would a Nuclear-Armed Tehran Behave?“, the report asserts that the acquisition by Tehran of nuclear weapons would above all be intended to deter an attack by hostile powers, presumably including Israel and the United States, rather than for aggressive purposes.

And while its acquisition may indeed lead to greater tension between Iran and its Sunni-led neighbours, the 50-page report concludes that Tehran would be unlikely to use nuclear weapons against other Muslim countries. Nor would it be able to halt its diminishing influence in the region resulting from the Arab Spring and its support for the Syrian government, according to the author, Alireza Nader.

“Iran’s development of nuclear weapons will enhance its ability to deter an external attack, but it will not enable it to change the Middle East’s geopolitical order in its own favour,” Nader, an international policy analyst at RAND, told IPS. “The Islamic Republic’s challenge to the region is constrained by its declining popularity, a weak economy, and a limited conventional military capability. An Iran with nukes will still be a declining power.”

The report reaches several conclusions all of which generally portray Iran as a rational actor in its international relations.

While Nader calls it a “revisionist state” that tries to undermine what it sees as a U.S.-dominated order in the Middle East, his report stresses that “it does not have territorial ambitions and does not seek to invade, conquer, or occupy other nations.”

Further, the report identifies the Islamic Republic’s military doctrine as defensive in nature. This posture is presumably a result of the volatile and unstable region in which it exists and is exacerbated by its status as a Shi’a and Persian-majority nation in a Sunni and Arab-majority region.

Iran is also scarred by its traumatic eight-year war with Iraq in which as many as one million Iranians lost their lives.

The new report comes amidst a growing controversy here over whether a nuclear-armed Iran could itself be successfully “contained” by the U.S. and its allies and deterred both from pursuing a more aggressive policy in the region and actually using nuclear weapons against its foes.

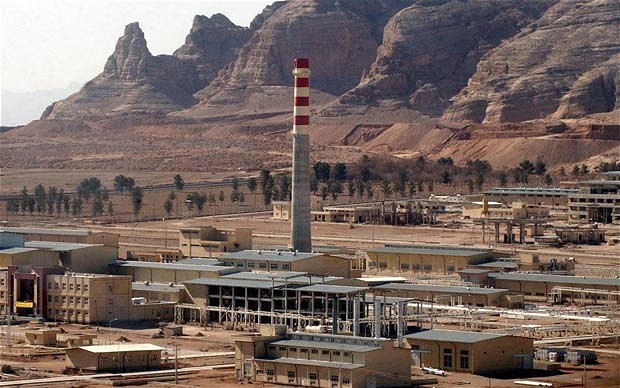

Iran itself has vehemently denied it intends to build a weapon, and the U.S. intelligence community has reported consistently over the last six years that Tehran’s leadership has not yet decided to do so, although the increasing sophistication and infrastructure of its nuclear programme will make it possible to build one more quickly if such a decision is made.

Official U.S. policy, as enunciated repeatedly by top officials, including President Barack Obama, is to “prevent” Iran from obtaining a weapon, even by military means if ongoing diplomatic efforts and “crippling” economic sanctions fail to persuade Iran to substantially curb its nuclear programme.

A nuclear-armed Iran, in the administration’s view – which is held even more fervently by the U.S. Congress where the Israel lobby exerts its greatest influence – represents an “existential threat” to the Jewish state.

In addition, according to the administration, Iran’s acquisition of a weapon would likely embolden it and its allies – notably Lebanon’s Hezbollah – to pursue more aggressive actions against their foes and could well set off a regional “cascade effect” in which other powers, particularly Saudi Arabia, Turkey, and Egypt, would feel obliged to launch nuclear-weapons programmes of their own.

But a growing number of critics of the prevention strategy – particularly that part of it that would resort to military action against Iran – argue that a nuclear Iran will not be nearly as dangerous as the reigning orthodoxy assumes.

A year ago, for example, Paul Pillar, a veteran CIA analyst who served as National Intelligence Officer for the Middle East and South Asia from 2000 to 2005, published a lengthy essay in ‘The Washington Monthly’, “We Can Live With a Nuclear Iran: Fears of a Bomb in Tehran’s Hands Are Overhyped, and a War to Prevent It Would Be a Disaster.”

More recently, Colin Kahl, an analyst at the Center for a New American Security (CNAS) who also served as the Pentagon’s top Middle East policy adviser for much of Obama’s first term, published two reports – the first questioning the “cascade effect” in the region, and the second, published earlier this week and entitled “If All Else Fails: The Challenges of Containing a Nuclear-Armed Iran,” outlining a detailed “containment strategy” — including extending Washington’s nuclear umbrella over states that feel threatened by a nuclear Iran — the U.S. could follow to deter Tehran’s use of a nuclear bomb or its transfer to non-state actors, like Hezbollah, and persuade regional states not to develop their own nuclear arms capabilities.

In addition, Kenneth Pollack, a former CIA analyst at the Brookings Institution whose 2002 book, “The Threatening Storm” helped persuade many liberals and Democrats to support the U.S. invasion of Iraq, will publish a new book, “Unthinkable: Iran, the Bomb, and American Strategy”, that is also expected to argue for a containment strategy if Iran acquires a nuclear weapon.

Because both Brookings and CNAS are regarded as close to the administration, some neo-conservative commentators have expressed alarm that these reports are “trial balloons” designed to set the stage for Obama’s abandonment of the prevention strategy in favour of containment, albeit by another name.

It is likely that Nader’s study – coming as it does from RAND, a think tank with historically close ties to the Pentagon – will be seen in a similar light.

His report concedes that Iran’s acquisition of nuclear weapons would lead to greater tension with the Gulf Arab monarchies and thus to greater instability in the region. Moreover, an inadvertent or accidental nuclear exchange between Israel and Iran would be a “dangerous possibility”, according to Nader who also notes that the “cascade effect”, while outside the scope of his study, warrants “careful consideration”.

Despite Iran’s strong ideological antipathy toward Israel, the report does not argue that Tehran would attack the Jewish state with nuclear weapons, as that would almost certainly lead to the regime’s destruction.

Israel, in Nader’s view, fears that Iran’s nuclear capability could serve as an “umbrella” for Tehran’s allies that could significantly hamper Israel’s military operations in the Palestinian territories, the Levant, and the wider region.

But the report concludes that Tehran is unlikely to extend its nuclear deterrent to its allies, including Hezbollah, noting that the interests of those groups do not always – or even often – co-incide with Iran’s. Iran would also be highly unlikely to transfer nuclear weapons to them in any event, according to the report.