by Shireen Hunter

Since the United States’ invasion of Iraq in 2003, which exacerbated Iraq’s ethnic and sectarian divisions and the manipulation of these divisions by regional and international actors, centrifugal tendencies in Iraq have become quite strong. For example, the country’s Kurdish population and, in particular, the leader of the autonomous Kurdish region, Masood Barzani, have openly said that the time for an independent Kurdish state has arrived. Others have talked about creation of an independent Sunni state in parts of Iraq.

The increasingly common talk of disintegration has not been limited to Iraq. In other Middle East states, similar trends are under way. In countries such as Libya, the reemergence of historical regional identities and rivalries, and hence the growth of centrifugal forces, has resulted from the fall of the central government as a result of external intervention. In Libya’s case, the intervention in 2011 took the form of French and British and then NATO bombings. Col. Muamar Qaddafi was deposed and killed, and the country fragmented. Turmoil there continues.

Meanwhile, outside interference by regional and international actors turned Syria’s popular protests in 2011 into an all-out civil war, which is still ongoing and threatens to end Syria’s existence as a single country. Sudan is already divided and is still fraught with strife and internal infighting in both its southern and northern parts. In other words, Sudan’s division has not brought peace and stability as some of the proponents of its division had claimed.

Even hitherto more prosperous and stable countries, such as Turkey, have also been affected by the fallout of these conflicts, especially those in Syria. For instance, Turkey’s Kurdish problem has once more become acute. In fact, Turkey’s recent military intervention in Kurdish-inhabited parts of Syria is directly related to its fears that an autonomous, or possibly even independent, Kurdish entity in Syria would strengthen separatist movements within Turkey as well. So far, Turkey has managed to reach a modus vivendi with the Kurdish entity in Iraq, but even there the independence ambitions of Masoud Barzani are a long term challenge for Ankara. Even Iran is not totally immune from the centrifugal trends unleashed by various Middle East wars. In fact, Iran’s regional rivals, notably Saudi Arabia, have been manipulating some of its disgruntled minorities in order to pressure the government in Tehran.

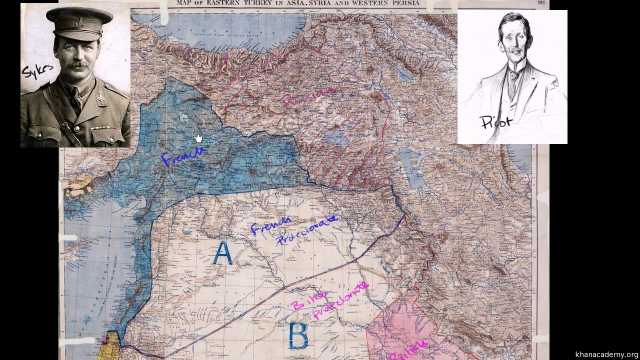

More seriously, there has been increasing talk, sometimes even by officials of major Western countries, to the effect that the Middle East’s present borders are not sacrosanct. On the contrary, according to this perspective most of these borders are artificial and were created as a result of bargaining and horse-trading among colonial powers, especially France and Britain. The number of articles and opinion pieces published about the need for another Sykes-Picot Agreement in the last year or so attests to the influence of this perspective. Many maps are published about how the borders in the Middle East and South West Asia could be rearranged (see, for example, “Blood Borders” in Armed Forces Journal. Some adherents of this perspective believe that rearranging borders according either to ethnic/linguistic or sectarian affinities might produce a more peaceful Middle East. However, they generally prescribe this method for those countries that they view as troublesome, such as Syria, Iraq, and even, should circumstances allow, Iran. In fact, there is a school of thought which maintains that Iran is too big for the major powers’ comfort, and thus even under a friendly regime could be challenging. Eventually, even Saudi Arabia might not escape these centrifugal trends, and thus those who recommend the rearranging the Middle East’s borders do not exclude it from their analysis. Ironically, the Yemen war, fought ostensibly to defend the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia, might even become a catalyst for its unraveling.

Yet despite the growth of these centrifugal tendencies and questions about the sanctity of current borders, the principle of territorial integrity also remains very important for all countries in the region. Even countries that might want to see their rivals broken up into smaller entities and even encourage separatist movements in their rivals’ countries still, because of their own vulnerabilities, pay lip-service to the principle of territorial integrity. Thus Turkey, after having done much to undermine Syria’s current government, now supports its territorial integrity, of course preferably without the Assad regime. Most Arab states voice support for Iraq’s territorial integrity, but preferably under a Sunni-dominated government, as in the past.

Redrawing Middle Eastern borders, however, would be neither easy nor desirable. Existing states would resist such efforts, which would lead to protracted civil wars. Intervention by outside actors is also costly and does not ensure success. Moreover, there is no guarantee that new borders, supposedly drawn on the basis of ethnic, linguistic, or sectarian affinities, would be any more stable than the existing ones. Take the case of a potential Kurdish state. Kurds for centuries have lived within different cultural settings – Turkish, Iraqi, Syrian, and Iranian (Kurds are ethnically, culturally, and linguistically close to Iranians). Even if a united Kurdish state could come together now, there would be sharp rivalries among those culturally diverse Kurds and their leaders, and they would face the challenges of developing a common language out of their many dialects and of creating the other paraphernalia of statehood. Relationships with their neighbors, from whom they would have separated, would also be fraught. They might even become embroiled in wars with their new neighbors. None of these concerns augurs well for potential new states which might emerge out of the wreckage of existing ones.

Yet clearly many peoples in the Middle East have serious cultural, economic, and political grievances that need to be addressed and cannot be ignored simply by summoning the principle of national and territorial integrity. But given the risks involved in the wholesale breakup of current states and a massive redrawing of existing borders, what is therefore to be done to address the grievances of minorities? The answer lies in less-centralized governments, greater economic and administrative autonomy for regions where minorities reside, a more equitable sharing of national resources, and greater cultural freedoms. For example, practices such as Turkey’s calling the Kurds “mountain Turks,” which fortunately it has now stopped doing, should be completely out of the question.

Another solution is regionalism and the encouragement of cross-border economic and cultural exchanges among those peoples who live within the borders of different states. For example, why should not there be economic exchanges among Turkish, Iraqi, Syrian and Iranian Kurdistan, or joint projects sponsored by their governments?

These suggestions may sound unrealistic or even downright naïve. Regional countries still fear themselves to be too vulnerable to internal and external pressures to envisage granting such sweeping rights to their minorities. The minorities meanwhile, are unlikely to accept such half-measures as opposed to the lure of having their own states, flags, and national airlines! Moreover, in order to succeed, such schemes as presented above would require key international actors’ acquiesce or, even better, active support. At the very least, in playing their power games, they should resist their impulses to manipulate the weaknesses and vulnerabilities of regional states.

Ultimately, it would be in the long term interest of key international players to support such programs as recommended here. Experience of the last three decades has shown that the consequences of war, internal strife, and fragmentation of vulnerable societies cannot be confined to their own borders and eventually are bound to affect others. The growth of international terrorism and the migration crisis, including the latest wave of both phenomena that has hit Europe so hard, are just two powerful reminders of such risks.

Photo: the Sykes-Picot map

Supporting the kinds of programs Dr. Hunter recommends sure doesn’t sound like the kind of thing a President Hillary would be interested in busying herself with. She’s more into the regime-change kind of project.

But it sure would be gratifying to see some kind of Kurdish objective come out of all this chaos. The Kurds got left behind in the big Middle East carve-up after WWI, so they’ve been waiting a long time for their issues to get addressed. Of course, it’s doubtful if the Palestinians will ever get theirs addressed; they’ll have to wait until the fall of the American empire.

With literally hundreds of Middle East tribes – it was, and remains, impossible to draw borders that could accommodate everyone. And all the more so when one considers the myriad of overlapping religious sects for said tribes.

(Note: One of the main objectives of Sykes-Picot – but mostly lost in any debate – was to diminish the pernicious factional/feudal effects of tribalism, and build up nationalism in its stead.)

Federalism and Regionalism may be, ultimately, the best solution – especially as 100 years of hindsight have failed to imagine more workable borders than the demonstrably unfairly-maligned Sykes-Picot effort.

However, because of a 100 plus years of minority abuse – to put it mildly – it is likely that the Kurds et al will see Federalism and Regionalism – at least for the present & near-future – as falling far short of redressing their longstanding grievances; ie, it will take a long time to build enough trust to share resources, etc.

In reply to delia ruhe (off-topic that it is):

The Arabs got sovereignty of 99% of the collapsed Ottoman Empire.

The Jews got sovereignty of 1% of the collapsed Ottoman Empire.

This was the first division of the collapsed Ottoman Empire.

Via the whole-cloth creation of an artificial ‘Palestinian nation’ (~1967), the Arabs are now tendentiously engaged in a most perfidious variation of gerrymandering through their demands to re-divide the territory.

In truth, this would constitute a re-re-division when one fairly recognizes the first re-division, Trans-Jordan, which was created whole-cloth specifically for any Arabs that might chose not to live under Jewish sovereignty.

Curiously, virtually all present-day so-called ‘Palestinians’ chose to live in sovereign Israel – indeed, they adamantly reject living in any future ‘Palestinian’ state!

In conclusion, the ‘Palestinians’ had their issues fairly addressed 100 years ago; they have no legitimate grievances now – at least none that even begin to measure to those of the Jews.

Very insightful Dr Shireen Hunter. With the exception of Iran and Egypt all other Moslem populations in the ME were nomads thus the reason for France and Britain being able to colonize them and later dividing their lands in to smaller pieces on an arbitrary fashion after the WWI. The Arab land was divided by the colonizers in order to keep them colonized under a false independent appearance in order to steal their resources for ever there after, in fact still continues! Further disintegration of the ME, by even the thought of having a Kurdish state created, would be disastrous for the region. However, the power players like Turkey, Iran and others like Iraq and Syria will never agree to having another state in their neighborhood to deal with in the future!

In reply to Monty Ahwazi (off-topic that it is):

Sykes-Picot did not divide “their lands in to smaller pieces”; indeed, the joined many tribal lands together to enable ‘nationalism.’ There was nothing “arbitrary” about it (see above comment).

If the objective of colonization was “in order to steal their resources,” then, demonstrably, it was a grand failure! Did individuals take advantage, yes – both ways.

Lastly, the Kurds – far more than the artificial ‘Palestinians’ – deserve their own state; ie, take all the arguments that are pro-Palestinian and add the merits that the Kurds are a real nation, and are not trying to annihilate an indigenous people.

The Ottoman Empire was collapsing for the 100 years prior to WWI, leaving lawless failed regions – including much of Jewish Palestine (there was no Arab Palestine until after 1967) – behind.

The Arab/Turk/Muslim world, from ancient times to the present, is made up of many hundreds of competing/combative tribes.

When Western individuals started doing business in the Middle East, violence was already a endemic problem.

No matter which tribe one traded with, other tribes either felt threatened, cheated, jealous, etc; the result being more violence.

Enter Colonialism

Western colonialism (unlike Islamic colonialism) was not created to conquer the world; it was an ad hoc development to deal with third-world violence. It brought in law, security, etc; all necessary to enable mutually-beneficial trade. (Please note: Since the end of Western colonialism, there has been a pernicious rise in failed states.)

As long as the West does trade with the Middle East, it will have to contend with tribal and Islamic violence, both there and at home.

History proves that marshaling violence is the only viable recourse; ignoring it, far from appeasing it, ever promotes more adventurism.

And even if the West could sever all ties, Islam’s colonialism would continue to export its violence to all corners of the world.