by Reza H. Akbari

Iran is celebrating the anniversary of its 1979 Revolution this month. Just as with the previous 40 years, an army of experts will attempt to dissect the exact nature of the Islamic Republic, its achievements, and a proverbial laundry list of its shortcomings. Akin to performing an autopsy, scholars will poke and prod at every organ in an attempt to shed light on various pathological features of the system. Some will forget that the body on the table is still alive, though the patient is still breathing and evolving despite its ailments. After close examination, analysts will emphatically provide their own prescriptions for the best path forward. The reality of Iran’s ruling system, however, is too abstract to fit squarely into any black-and-white diagnosis.

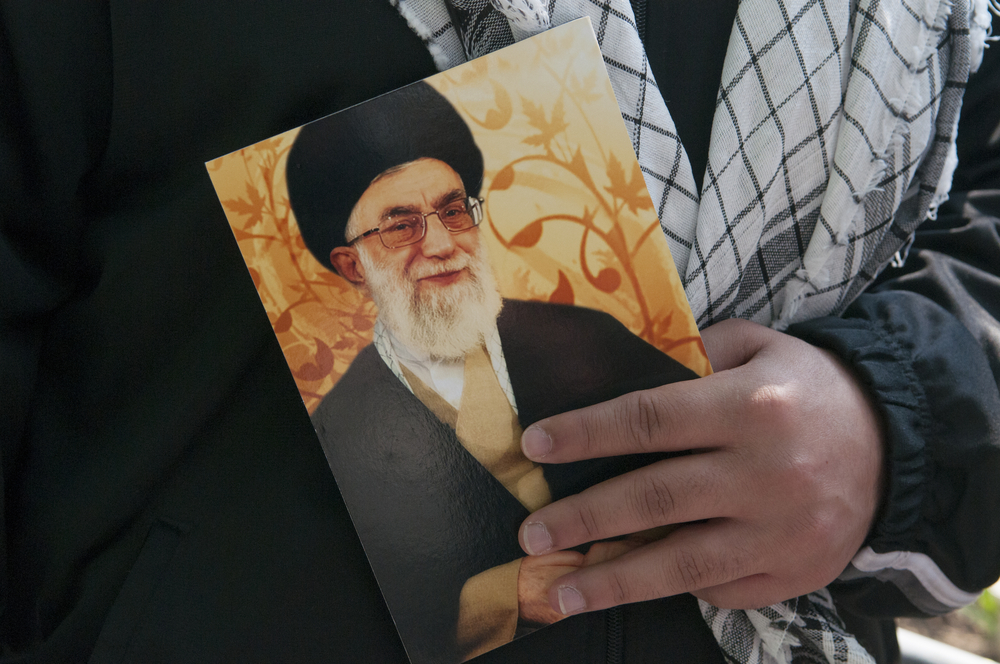

In defiance of four decades of relentless categorical analyses, the Islamic Republic still refuses to neatly fit into any one explanatory framework. Is it an authoritarian regime incapable of change, or is it capable of incremental reforms? Is it a system based on unwavering Islamic ideology, or does its politics revolve around constructed religious doctrines? Is the Supreme Leader an omnipotent figure whose every command is executed without dissent, or is he susceptible to persuasion? Do the semi-democratic institutions of the system play significant roles, or are they just a ploy to create the outward-facing facade of a responsive government?

Many attempts have been made to provide concrete answers to these, and other, questions, but there does not appear to be any clear-cut explanation for the ever-shifting, multi-faceted, and often paradoxical political life in Iran. After 40 years, scholars, observers, and politicians alike have not managed to build a consensus over even the most fundamental aspects of the ruling system. The all-too-common unicausal narratives about the Islamic Republic fall way short of capturing the full picture. Like a shape-shifter, the 1979 Revolution and the post-revolutionary government in Iran continue to adopt different forms and identities, with each phase requiring a new explanation or revision to past assumptions.

Post-revolutionary Iran is riddled with ideological and political inconsistencies, but what has remained constant has been the perpetual evolution of the power, identity, and clout of institutions and individuals within the system. New institutions have popped up to address gridlocks (the Expediency Council), offices have been phased out (the elimination of the post of prime minister), and councils have been formed to address local demands (the city and village councils). Looking at a single snapshot of what is taking place in Iran could easily result in either a darker or more optimistic picture of the power of a given individual or institution. However, a much more cohesive reality could be painted by widening the lens to look at the waxing and waning power of players over time.

A cursory look at the history of the Expediency Council, for example, could demonstrate how the powers of this constitutional body have ebbed and flowed within the context of external pressures and various internal factional rivalries. For Iran, 1988–1989 was a crucial period. It was the end of the Iran-Iraq War and the country was transitioning from a wartime economy to peacetime reconstruction. Many emergency laws were passed, and a major gridlock emerged between an Islamic-left parliament and a traditionalist-right Guardian Council, the 12-member body in charge of approving laws the parliament passed. As such, the Expediency Council, in charge of resolving conflicts between these bodies, grew beyond its designated role and assumed the authority to pass extensive emergency laws. Since then, however, the power of the council has been severely curtailed due to objections from parliament and rival infighting between factions. This institution has been weakened for now, but if history is any guide, the Expediency Council could easily gain its past prominence once again if the conditions call for it.

Iran’s political elites have also continued to evolve. Following the death of Akbar Hashemi Rafsanjani—who, among many other roles, served as the country’s president from 1989–1997—many experts began to label him with certain factional affiliations or political leanings. But the reality of Rafsanjani’s life was as dynamic and multifaceted as the Islamic Republic. He was one of the founding fathers of the system. In 1989, he laid out the legal framework for market privatization. He was accused of ordering foreign assassinations of dissidents in 1992. From 1995–1997, he dealt with serious accusations of fraud and corruption. In 1997, he began to inch away from the Supreme Leader and supported the reformist presidential candidate Mohammad Khatami. After the contested 2009 presidential election, he attempted to act as a powerbroker between the Supreme Leader and the opposition faction. He was quickly sidelined, and his children were jailed. The arc of Rafsanjani’s political life resembles the flexibility and fluidity that the system has shown over the past 40 years when faced with necessity—or, as Ayatollah Khomeini called it, expediency. Just like the system he lived to protect, Rafsanjani evolved, shed many skins (not all good), and adapted to numerous internal and external challenges. Trying to describe Rafsanjani, or the system as a whole, with one simple definition would be akin to catching a cloud in a jar—fun to try, but ultimately impossible.

The game on the Islamic Republic chess board is constantly in motion, often in seemingly arbitrary ways. Some moves are, at times, forced by civil society, internal political infighting, or foreign powers. This fluid reality creates a confusing environment for players and observers alike. Yesterday’s unthinkable actions may be considered prudent today, and influential political figures of the past can easily be debilitated by a pervasive opposing faction in the future. While analyzing the often-unpredictable system in Iran, it is crucial to remember that revolution, in the mind of its founders and citizens, is not an event with a definite start and end date. It is an ongoing process and any conclusive summary would impose an arbitrary closure on a continuous evolution. Annual checkups are indeed necessary, but let’s remember that the patient is still alive during the examination.

Reza H. Akbari (@rezahakbari) is a program manager at the Institute for War and Peace Reporting. He conducts research on Iranian domestic politics, U.S. foreign policy toward Iran, Shia politics, and political transition.

It is wonderful to read how philosophical and apologetic revolutionaries are about a bunch of terrorists.

Yet another author insulted by Mostofi who claims to be here for “There is a reason I post here. It is to prove that Iranians cannot discuss controversial political discussions in a civil manner.” …. Lol …

Thank you Reza Akbari for your preliminary autopsy of the regime in Iran for the past 4 decades. As your description indicates the current regime has been and still is fluid and malleable daily. Perhaps one major reason for being fluid could be attributed to the fact that the Mullahs have never been experts in leading a relatively large nation politically and or economically at the same time dealing with other nations globally. May be by now they have completed their grade school levels politically and economically. If that’s the case this fluidity may continue for years before they’ve gone through their high school and college levels of becoming experts in sociological, political and economical lessons for domestic and international consumption.

But leading a complex and diverse society like Iran by experimentations could be tough and painful for all.