by Peter Jenkins

It is striking how often opponents of a nuclear agreement with Iran resort to an ethical non-sequitur. They are fond of arguing that, because the Iranian government tortures political prisoners or supports entities that commit violent acts for political ends, the same government is bound to breach whatever non-proliferation pledges it may offer.

This is akin to arguing that, because your neighbor beats his wife, he must surely be stealing from his employer—or because he cheats at poker, he must surely be a drug addict.

The intention behind this fallacy is to harness emotion to the anti-Iranian cause. The opponents of a deal are trying to arouse indignation and aversion in the hope that these emotions will cloud judgments. Another emotion they seek to arouse is fear. For that purpose they summon up the “regional hegemon” bogey, the mysteries of the military site at Parchin, and Iran’s development of medium-range missiles and a cyber-warfare capability.

There is hope to be drawn from all this. It suggests that opponents have despaired of winning the debate about a nuclear deal through reasoned argument. It suggests they have come to understand, consciously or unconsciously, that they have no rational counter to the administration’s case for an agreement.

Interests Trump Ethics

That said, the argument that the United States ought not to be cutting nuclear deals with a government that has a grisly human rights record and has sponsored terrorist acts is not vacuous. There is more to it than an appeal to emotion.

The argument can be rephrased as follows: can there be any justification for negotiated agreements with state or non-state actors who violate fundamental norms of behavior?

An answer can be found in the French concept of raison d’état, which equates to “paramount interest.”

The post-1945 period—an age in which Western democracies have tried harder than ever to promote Western values worldwide—offers many instances in which those democracies have put strategic interests ahead of ethical promotion.

In the 1970s, for example, the United States was happy to do business with anti-communist military regimes in Brazil, Argentina and Chile, though these regimes were known to be torturing and murdering political opponents. Washington’s overriding interest was to minimize Soviet penetration of Latin America.

In the 1990s the British government was ready to negotiate with the Provisional Irish Republican Army, which had the blood of many innocents on its hands, to put an end to political violence in Northern Ireland and English cities.

For decades the French government has held its nose and cozied up to African strongmen although the latter have paid scant regard to Western values. In that region France cannot afford to be ethically fastidious.

In 2003 the United States and Britain supped with Muammar Qaddafi to obtain the surrender of his chemical weapons and crates full of uranium centrifuge components.

Of course this pursuit of strategic interests has not gone unquestioned by idealists. But these idealists have been outnumbered in each case by pragmatists, for whom the defense and promotion of ethical values is a luxury compared to a nation’s interest in peace, security, and prosperity.

US Interest in an Agreement

When it comes to Iran in 2015, the Western democracies have much to gain by holding their noses. The prospective agreement will minimize the risk of Iran’s elite using uranium enrichment technology or plutonium-breeding reactors to produce the fissile material needed for nuclear weapons.

The only alternative to risk minimization in this case, experience has taught us, would be the armed invasion and lengthy occupation of Iran. The huge costs that this alternative would entail cannot be justified in the absence of evidence that Iran is hell-bent on acquiring nuclear weapons.

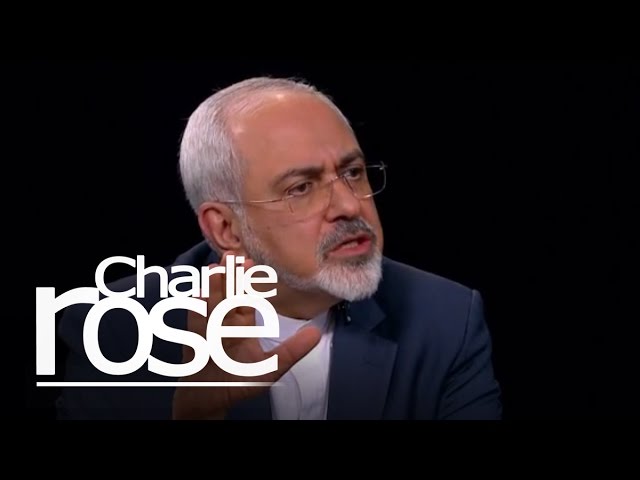

In fact, the contrary seems to be the case. Iran’s foreign minister told Charlie Rose on nationwide TV: “We have taken a decision not to acquire nuclear weapons.” Able diplomats—highly able in this case—may refrain from telling the truth through equivocation, but they do not volunteer lies. They know that diplomatic credibility does not recover from being caught out in a deliberate falsehood.

A nuclear agreement with Iran can also:

- bring to an end a dispute that has damaged the International Atomic Energy Agency by politicizing its Board of Governors and laying the current director-general open to the perception that he has been too ready to listen to malevolent allegations.

- demonstrate that the permanent members of the UN Security Council are capable of acting unanimously to uphold the global nuclear non-proliferation regime;

- encourage Iran’s leaders to look for other areas in which they can benefit by cooperating with the West;

- secure a return to the Iranian market for Western traders and investors;

- open up the possibility, over time, of changes to the political climate in Iran that will reduce toleration for the mistreatment of domestic opponents and for sponsoring political violence abroad.

When there is so much to be gained by holding one’s nose, pragmatism and expediency must prevail. Winston Churchill, as so often, showed the way. In 1941, desperate for allies, he remarked of Stalin: “If Hitler invaded Hell, I would make at least a favorable reference to the devil in the House of Commons.”

Great piece.