by Paul R. Pillar

The dramatic and fast-moving events in U.S.-Iranian relations over the past few days underscore, among other lessons, the following two. One is that results matter. No matter how hard the naysayers have striven to say nay, they have offered no alternative to actual U.S. policy that could have yielded results as favorable. And it’s not as if there hasn’t been ample experience to test what alternatives might have done. With regard to Iran’s nuclear program, years of nothing but pressure and sanctions brought only years of an expanding program with ever more centrifuges spinning. It was only through engagement, negotiation and compromise that the most strenuous restrictions on, and monitoring of, a national nuclear program that have ever been negotiated were achieved. As for Iranian-Americans who were unjustly imprisoned, they and perhaps others as well would have been imprisoned whether or not U.S.-Iranian relations were in a deep freeze. (A couple of the men just released by Iran had been arrested before the nuclear negotiations even began.) They were freed only because the relationship thawed. As for the naval encounter in the Persian Gulf, despite the erroneous attempts by critics of the administration to depict as an Iranian provocation an incident that instead consisted of U.S. Navy craft making a still not fully explained incursion into Iranian territorial waters, it is hard to imagine an outcome as favorable as the one that ensued if there were not the diplomatic channel, established in the course of the nuclear negotiations, to achieve that outcome. Again, past experience strongly suggests that with a frozen relationship the outcome would have been worse.

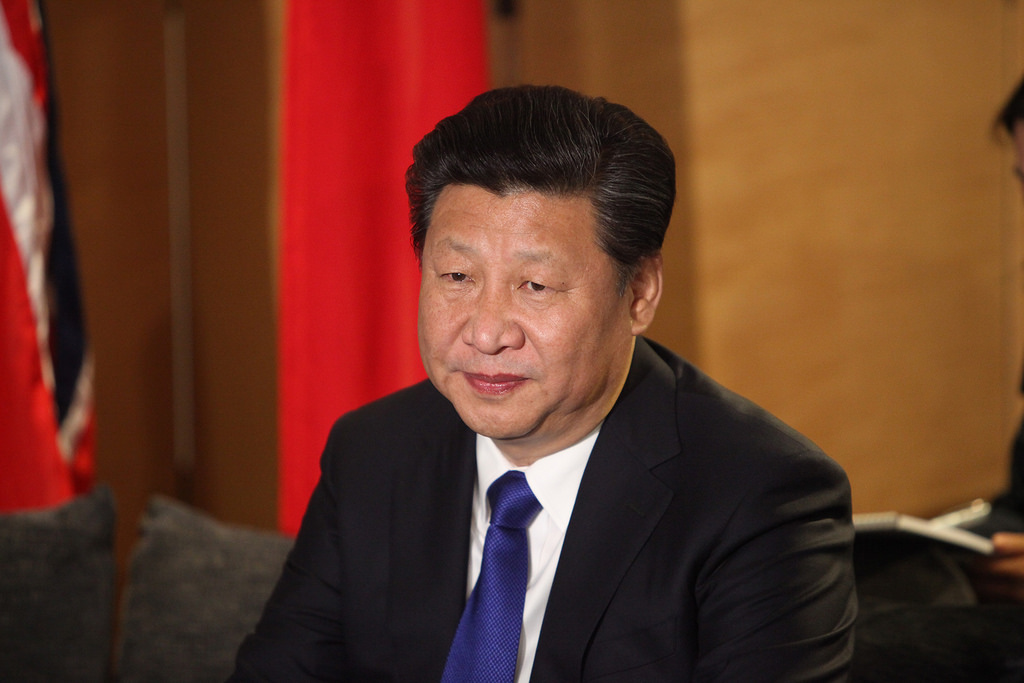

A second major lesson concerns the mistake of treating relations with any country customarily labeled as an adversary as if the entire relationship were zero-sum, leading to policies that try to oppose the other country at every turn, no matter what that country is doing and no matter how what it is doing actually does or does not relate to U.S. interests. This mistake has arisen regarding U.S. policies toward some other countries besides Iran. Joshua Kurlantzick of the Council on Foreign Relations makes a thoughtful argument in a recent article that the Obama administration has committed this mistake in its policy toward China, in which the administration’s “Asia strategy has been to fear and combat nearly every move by China to flex its muscles.” The ill-advised nature of such a strategy is illustrated by the feckless U.S. attempt to dissuade other states from participating in the new China-initiated Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank. A better strategy, says Kurlantzick, would be to save opposition to China for those issues on which Beijing’s behavior really does run up against important U.S. interests, such as the unjustified Chinese attempt to stake vast territorial claims in the South China Sea.

On Iran, the corresponding mistake has been made not by the Obama administration but instead by its critics who believe that Iran ought to be opposed everywhere, all the time, no matter what it is doing, thus treating anything in Iran’s interests as if it were by definition against U.S. interests. Some of the chief underpinnings of this posture have to do with idiosyncrasies of current American politics: the influence of the right-wing Israeli government, which wants to keep Iran forever ostracized for reasons that do not correspond to U.S. interests; and the impulse in the Republican Party to oppose anything Obama proposes. Also underlying the posture, however, is a more general American tendency to view the outside world in black-and-white terms with a rigid division between foes and friends. The Obama administration has pushed back against these tendencies with its nuclear diplomacy on Iran, but the tendencies are so strong that the administration still has had to bow to some of the Iran-is-always-bad mindset as a way of husbanding its political capital and protecting its most important achievements.

The oppose-an-adversary-everywhere approach is harmful to U.S. interests in several respects, starting with the fostering of a mistaken view of exactly what those interests are. They are not really zero-sum vis-a-vis China, Iran or any other country. The first step in upholding U.S. interests is to have a clear and undistorted view of the interests themselves.

The zero-sum approach impedes fruitful cooperation with the other country in question. This means not only the big initiatives (such as the Shanghai Communiqué with China and the nuclear agreement with Iran) but much else besides. The Obama administration, despite being overeager to counterpunch Beijing in Asia, has gotten some useful cooperation from China on climate change and the negotiation of the Iran agreement. But there is plenty more such cooperation that is needed; the handling of North Korea probably tops the list. With Iran, beyond nuclear matters the most prominent current area of shared interest where cooperation is important is opposition to ISIS and similar violent Sunni extremism.

The inclination to oppose the other state across the map gets the United States into costly and disadvantageous commitments. Kurlantzick mentions, for example, some questionable U.S. policies in Southeast Asia that stem from the inclination to oppose Chinese influence everywhere. In the Middle East, the often-asserted and very incorrect theme that Iran is “destabilizing the region” and that its influence must be countered everywhere has led to such mistakes as U.S. support for the ineffective and destructive (and deplorable on humanitarian grounds) Saudi-led military campaign in Yemen.

Economic sanctions, as a favorite tool of those who want to take a uniformly negative approach to a country labeled as an adversary, have come to be treated as if they were a positive thing in their own right. It is as if schadenfreude were a U.S. national interest. It isn’t. The United States gains no benefit from economic weakness in Iran, China or elsewhere. (For a reminder, check what your stock portfolio has done since the start of the year.) In important respects the United States has an interest in healthy economies in those and other places. And U.S.-imposed sanctions inflict direct harm on the United States itself. Lost sight of long ago in many discussions in the United States about sanctions against Iran is that they are of no good to the United States at all except insofar as they shape Iranian motivations to do something such as agree to major restrictions on Iran’s nuclear program.

The prisoner exchange needs to be seen in this light. The men released by the United States were charged with no offense other than violation of U.S.-imposed economic sanctions against Iran—and in particular the nuclear-related sanctions, which have served their purpose with implementation of the nuclear agreement and are no longer of use. In this respect what the United States gave up in the swap was minimal indeed.

The zero-sum approach of opposing everything the other country does fails to take account of internal political competition in that country. Such disregard of the other side’s domestic politics tends to work to the disadvantage of U.S. objectives. In this respect, the prisoner release is an important statement about the state of play of political contests inside the Iranian regime. Strong forces that for their own reasons resist a thawing of the relationship with the United States are still part of that regime. Those hardline elements, which have largely had control of the Iranian judiciary, were responsible for the original incarceration of the prisoners who were freed. Release of those prisoners indicates that the more moderate and progressive elements in the regime, including President Rouhani, have gained enough influence and won enough internal arguments to bring about the release. Rouhani and his allies will be able to retain such influence only as long as they can demonstrate that cooperation with the United States rather than confrontation pays off for Iran. If U.S. policy were to change in a direction that made it harder for the moderates to win such arguments, then we would see Iran taking more dual-national prisoners and releasing fewer of them.

Currently there does not appear to be a comparable internal political dynamic in China. Control and stifling of dissent seem to be watchwords of the regime under Xi Jinping. But perhaps someday, if political pressures in China catch up with economic change, the issue may be germane there, too. U.S. policy can matter, not in stoking counterrevolution but in helping to shape political evolution.

The black-and-white approach to foes and friends makes it seem easy to think about relationships that actually are complicated. And some primal urge gets satisfied by sticking it to someone we’ve decided we don’t like. But that’s a poor way to advance our own nation’s interests.

This article was first published by the National Interest and was reprinted here with permission. Copyright The National Interest.

Superb article.

The negotiation and implementation of the JCPOA has to go down in history as the one truly unambiguous foreign policy triumph of the early 21st century. Just a few short years ago Iran was an “enabler of terrorism” (Washington-speak for funding of Palestine’s active defenders, Hamas and Hezbollah) and a member of an “axis of evil” (i.e., in Washington’s view, three countries in need of regime change). Is it, then, any wonder that thinking outside those neatly-labelled boxes is way beyond the ambitious think-tankers, halfwit politicos, and assorted other binary thinkers who have invested hot air and considerable money into denying the P5+1 – especially Obama – this success?

As for China, I don’t personally know anybody who can’t understand why China needs to do something to protect its vulnerable east coast against a pushy American military famously looking for trouble. Building a military base, complete with runway, just off its coast is probably the best answer. But China should be negotiating with those little nations who also have a claim on the (uninhabitable) islands in the China Sea. Is it beneath Washington’s dignity to assist the relevant parties to the negotiating table? If American can negotiate a successful deal with its “enabler of terror” and its “axis of evil,” surely it can help China and her little neighbours find a win-win solution.

The negotiation and implementation of the JCPOA has to go down in history as the one truly unambiguous foreign policy triumph of the early 21st century. Just a few short years ago Iran was an “enabler of terrorism” (Washington-speak for funding of Palestine’s active defenders, Hamas and Hezbollah) and a member of an “axis of evil” (i.e., in Washington’s view, three countries in need of regime change). Unfortunately, thinking outside those neatly-labelled boxes is way beyond the ambitious think-tankers, halfwit politicos, and assorted other binary thinkers who have invested hot air and considerable money into denying the P5+1 – especially Obama – a diplomatic success.

I’m wondering if a Hillary administration might internalize that success and use it as a model to make some friendly adjustments to its “Pacific pivot.” I’m anything but confident.

I don’t personally know anybody who can’t understand why China needs to do something to protect its vulnerable east coast, given a pushy American military famously looking for trouble. Building a military base, complete with runway, just off its coast is probably the best answer. But China should be negotiating with those little nations who also have a claim on those rocks that poke up above the surface of the sea. Would it be damaging to “America’s interest” for Washington to assist the relevant parties to the negotiating table? If American can negotiate a successful deal with its “enabler of terror” and its “axis of evil,” surely it can help China and her little neighbours find a win-win solution. Will it choose a diplomatic path or continue to whip up fear and resentment among Americans vis-à-vis China? Stay tuned.