by Robert E. Hunter

In the ways of the world, sometimes objectively little events can symbolize much greater ones. Thus the determination by the International Atomic Energy Agency (IAEA) that Iran has complied with requirements of the Joint Comprehensive Plan of Action (JCPOA), limiting its nuclear work and triggering the lifting of some economic sanctions, is trumped in the American public imagination by two other events. One was the swift resolution of the incident of the straying of a US Navy boat into Iranian territorial waters. The other was the conclusion of a “prisoner swap” of Americans and Iranians on the same day as the IAEA declaration. (Just coincidence? “Sometimes,” Sigmund Freud said, “a cigar is only a cigar.”)

In terms of the atmospherics that are so important in relations between countries, provided they have a realistic underpinning, it now seems that other developments in Iran’s relations with the West will be possible. At least the trajectory is in the right direction.

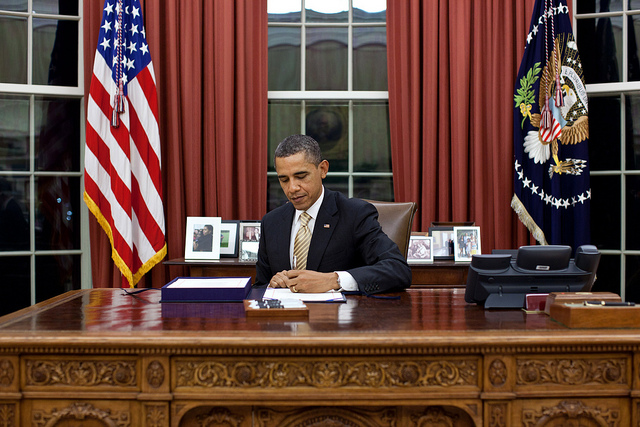

Hopes can always be dashed. But better hopes than fears. As of now, it is obvious that President Barack Obama’s gamble in negotiating with Iran—negotiations ably conducted by Secretary of State John Kerry—has enhanced both the reality and the perception of security in the Persian Gulf. There remain malcontents. But they are so far being proved wrong, at least in regard to overall regional security. Meanwhile, the national ambitions of various Arab countries, plus Turkey and Israel, to ensure Iran’s perpetual isolation, have been thwarted.

The catch-and-release of US Navy personnel, plus Iran’s recent firing of a missile within a mile of a major US warship, were minuscule matters in comparison with the 1962 Cuban Missile Crisis with the Soviet Union. But there is one commonality. Then, both superpowers understood the risks they had each taken and the need to modify behavior. That produced the Limited Test Ban Treaty the following year. The “naval incident” with the US Navy’s boat showed that Iran decided not to blow up wider diplomatic achievements, as it could have done. This was a victory for pragmatic elements in Teheran over the hotheads. The coolness of the US handling of the missile-firing in the Persian Gulf showed something similar. Although it took many years for the US and Soviet Union to stabilize and then end confrontation, both sides internally subscribed to the idea that it was prudent to start the long process toward a different relationship.

Recent events in the Persian Gulf have also showed the leaderships in both Teheran and Washington the need to keep tight control over their militaries. Thus Iran risked much by failing to prevent some Navy or IRGC commander from firing a missile close to a US warship. And someone in the Pentagon didn’t get the message that this was no time to be running naval exercises, for whatever reason, in the Persian Gulf. (It is also time to rethink the policy of keeping the Gulf stuffed with Western warships, which have little military or diplomatic utility. Iran knows that the US has no need for local deployments to be able to devastate Iran, and the Arab states know that Iran does not currently pose a military threat. Their concern is with US diplomatic allegiance, not demonstration of US military might.)

Indeed, the twin naval incidents showed, once again, that with naval vessels things do “go bump in the night”—and during the day. All mariners know that. That is why in 1972, at the height of the Cold War, the US and the Soviets concluded an Incidents at Sea Agreement (which is still in force with Russia), so that accidents could be kept from escalating politically. It worked. It is long past the time when there should have been a similar agreement involving all nations with ships in the Persian Gulf. Secretary of Defense Ashton Carter and his Iranian counterparts should take note. Both countries have been lucky in recent weeks. But luck is not a bankable currency.

Of course, the caterwauling in US politics is now in full swing over the lifting of some sanctions against Iran. If the presidential candidates are serious—a big if in a presidential campaign—they must know that, whichever one accedes to the Oval Office, he or she will be thankful for the JCPOA. All the campaign rhetoric about abandoning the deal is just that, campaign rhetoric.

Strangest of all is the bombast coming from Hillary Clinton, who already has her sights on the presidential election, not the primary season. She wants more sanctions over some Iranian missile tests, and she promises to “distrust [Iran] and verify”—thus making President Ronald Reagan (“Trust but verify” with the Soviet Union) look like a dove! Her comments are all the stranger given that Clinton was secretary of state and thus cannot be totally innocent of US-Iranian nuclear diplomacy. This is true even though she was never enthusiastic about the negotiations. According to her memoir, Hard Choices, she did what she could to scotch the possibilities of an agreement with Iran, whether realistic or not, fostered by the presidents of Brazil and Turkey and publicly endorsed by President Obama. Further, along with too many of her other first-term Obama cabinet colleagues, she has broken with two centuries of US tradition by attacking the policies of a president whom she served while he is still in office.

Perhaps Iran and the West, led by the US, are now turning a page in their relations, which can produce huge benefits. But the requirements seem to rest on the conduct of domestic politics in Iran and the US as much or even more than their interactions with one another. In the US, Obama has had the courage to take on the potent Israeli lobby and the less potent Arab lobby. Many of Israel’s supporters in the US—in Congress, the media, think tanks, and on the hustings—will continue to try making Obama fail in his support for the JCPOA and efforts to test possibilities in other parts of relations with Iran. They are acting in opposition to clear US national security interests. We must all hope that it is they who will fail.

Clinton sold the Palestinians down the river. I don’t expect his wife to behave any differently.