by Eldar Mamedov

In a flurry of the articles written in the aftermath of the failed coup aftermath in Turkey, some analysts argued that the victorious Turkish president Recep Tayyip Erdogan will now launch a wholesale Islamization of the country. Soner Cagaptay, the Turkey analyst at the Washington Institute for Near East (WINEP), takes the argument a step further in his recent piece in the Wall Street Journal, which draws direct parallels between the processes unfolding in Turkey and the Islamic revolution in Iran in 1979. His conclusion is that the chances of an Islamic revolution in Turkey have never been higher.

Cagaptay established himself as a serious scholar of Turkish identity and politics with his book Who is a Turk: Islam, Secularism and Nationalism in Modern Turkey. This book is required reading—for policymakers, diplomats, and others—trying to understand Turkish identity struggles in the 20th century. But in his work at WINEP, in line with the institution’s neoconservative agenda, Cagaptay has occasionally traded analytical rigor for sensationalist fear-mongering with Iran at its center. His piece warning that Turkey is facing its “Iran-1979 moment” is a case in point.

First, the unfolding Turkish drama is not about Islam, but power politics. Erdogan is using the “God-given gift” of the coup to purge the state of his real and perceived enemies and accelerate the march toward his long-cherished dream of an all-powerful executive presidency. This has very little to do with Islam, beyond an instrumentalization of religious feelings by Erdogan in order to mobilize his supporters for the attainment of this very secular goal. Erdogan, while outwardly devout, is trying to maximize his power within the secular system established by Mustafa Kemal Ataturk. It’s not the secularism, but the few remaining checks and balances that stand in his way that he is busy dismantling.

Moreover, although the leader of the Iranian revolution, Ayatollah Khomeini, made very clear from the beginning that he envisioned an Islamic republic for Iran, Erdogan repeatedly stressed his commitment to secularism. For example, he famously urged the Egyptian Muslim Brotherhood to embrace secularism in the wake of the Arab Spring and, later, defended this principle after the suggestion of the president of the Turkish parliament Ismail Kahraman that Turkey needs a “religious constitution.”

Khomeini was surrounded in 1979 by revolutionaries, both religious and secular, while Erdogan’s current entourage includes practically no committed Islamists. Most of his ministers and advisers are conservative Anatolian “fat cats” interested in power and money, not revolutionary utopias, Islamic or otherwise. Current Prime Minister Binali Yildirim is a case in point: an experienced and competent manager who oversaw budgets of billions of dollars in his previous capacity as the minister of transport. That’s hardly the stuff of Islamic revolutionaries.

The second difficulty with the “Turkey 2016 equals Iran 1979” thesis has to do with governance: who will draft the laws and what is going to be the institutional set-up of the Islamic Republic of Turkey? Ayatollah Khomeini had a clear blueprint for his Islamic Republic with the concept of velayat-e faqih, or governance of the jurist, at its heart. That the Shiite clergy in Iran always preserved a degree of independence vis-à-vis political power has enabled it to provide necessary religious and legal expertise to the new system.

In Turkey, by contrast, the Sunni clergy has always been politically passive and subordinated to the state. With the establishment of the Kemalist republic, all clergy became state officials through the Diyanet, the directorate for religious affairs. The nominally Islamist Justice and Development Party (AKP) preserved this system, essentially designed to control religion. Turkish imams are trained to provide religious legitimization for the state’s policies, whatever those happen to be, not to build theocracy. And Erdogan himself is a populist leader, not a religious man possessing enough qualifications to conceptualize an Islamic rule. He’s more an Ahmadinejad than a Khomeini.

Besides, replacing the current secular law with Islamic law would be enormously difficult. A re-introduction of the death penalty is a case in point. As notable Turkish Islamist Abdurahman Dilipak recalls, such a step would not be a problem from an Islamic point of view, but it would conflict with the country’s international legal obligations and terminate its EU accession negotiations for good. Since the EU is by far Turkey’s largest trade partner and foreign investor, a break-down in relations would lead to deepening economic troubles and undermine Erdogan’s main selling point: a relatively successful economy.

Third, Erdogan has exploited Turkish nationalism much more than Islamism in his pursuit of absolute power. His decision to re-launch the war against the Kurdistan Workers’ Party (PKK), not calls for banning alcohol or a compulsory headscarf, allowed him to turn the tide of the parliamentary elections in November 2015 in his favor. By waging war on Kurds, Erdogan has successfully absorbed Turkish far-right nationalists known as the Grey Wolves. Those who lynched pro-coup soldiers during that fateful night of July 15 were not only bearded Islamists but also fascist Grey Wolves, who have nothing to do with Islam.

Cagaptay is right, however, to observe that Erdogan’s own policies in Syria have reinforced jihadist sentiments in Turkey. But he is wrong in suggesting that Erdogan now can somehow harness these forces “to usher in an Islamic revolution.” In reality, the extreme jihadists in Turkey despise Erdogan and consider him an apostate, as the Islamic State magazine Dabiq has made clear.

The real worry about Turkey is not that it is becoming a Sunni version of Iran’s Islamic Republic. Rather, the current purge may help consolidate an authoritarian one-man rule underpinned by a combination of superficial religiosity and extreme Turkish nationalism disguised as kitsch neo-Ottomanism. Overblown scenarios about Turkey becoming Iran-1979 only serve to obscure this real threat.

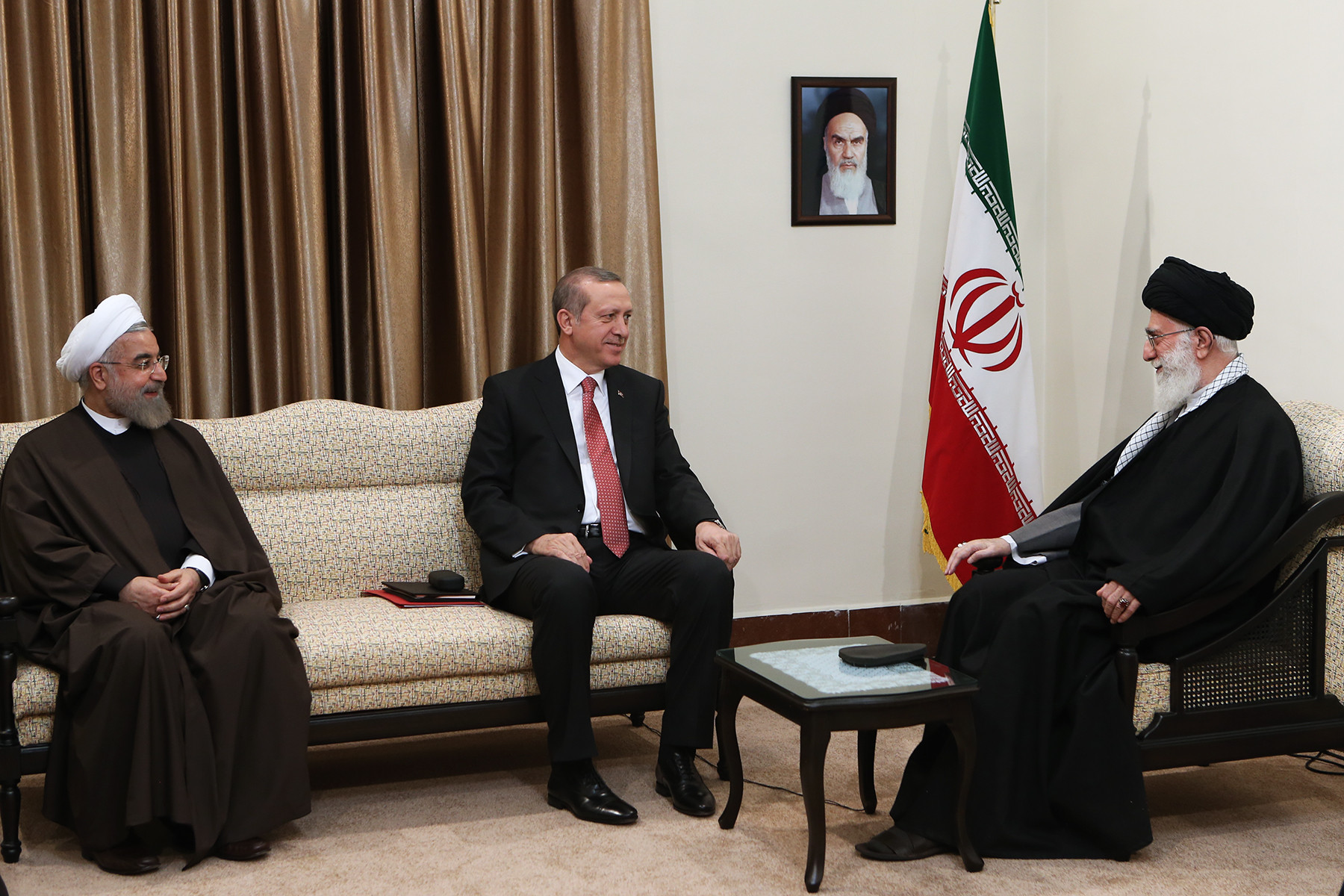

Photo: Iranian President Hassan Rouhani, Turkish President Recep Tayyip Erdogan, and Iranian Supreme Leader Ali Khamenei all meet below a picture of Ayatollah Khomenei.

This article reflects the personal views of the author and not necessarily the opinions of the European Parliament.

Good analysis. Every time I see the acronym WINEP, I cringe and feel nauseated…sort of like AIPAC.

I disagree with this analysis. Just because there is not the emphasis on religion,

does not mean that this is the focus of where he is going and away from any form

of democracy. You don’t round up the Legislature and Judiciary and act in this fashion.

I disagree with the idealist conclusion.

Even if Erdogan does not want an Islamic Republic, he may be forced to move toward it. He owes his survival to the mosques and to some Turks opposed to what they perceived as the return to military rule. After the hatred for Gulen, his best weapon to manipulate the people is clearly Dyanet and Islam.

To impose his megalomaniac authority, Erdogan cannot favored more secularism as secularism comes with freedom of expression and Erdogan is opposed to anything that would prevent him from reaching his goal.

He is conveniently using Gulen as the Boogey man but sooner or later he will be obliged to favor Islam as the more effective tool of repression.

Erdogan has become a liability for Turkey and may drive the country to a social disaster after having brought it to economical success. His removal is overdue.