by Giorgio Cafiero

The flag of Catalonia and pro-Catalan independence posters are virtually everywhere in Barcelona. Each night at 10 pm, Catalonians who call for their autonomous region to separate from Spain bang pots and pans to express their support for a referendum, which the Catalan parliament approved and scheduled for October 1. If held, the referendum, which Spain’s central government and the country’s constitutional court have declared “illegal” and “unconstitutional,” will offer Catalonians an opportunity to vote in favor of independence from Spain.

Catalonian nationalism, deeply rooted in northeastern Spain, is nothing new. It was a root cause of the Spanish Civil War, and Catalonian nationalism grew significantly after the Francisco Franco regime, which held power from the 1930s to the 1970s, rammed Spanish nationalism down the throats of Catalonians. A common narrative among Catalonians is that they continue to live under an oppressive Spanish occupation.

The idea of separating from the rest of Spain and establishing an officially independent Catalonian state became increasingly popular as a consequence of the 2008 global financial crisis. The perceptions that too much of Barcelona and the rest of the region’s wealth had gone to poorer parts of Spain since the global crash have added momentum to the movements and organizations in Catalonia that call for independence. A common argument made in favor of independence is that the region’s 7.5 million could benefit from improved economic conditions with higher salaries if Catalonia separated from Spain. This month, Carles Puigdemont, the president of Catalonia, articulated his belief that Prime Minister Mariano Rajoy’s government was bringing authoritarianism of the Franco era back to Spain and damaging the country’s democracy. This month, too, Puigdemont condemned Madrid’s crackdown on the referendum as a “coordinated aggression” by a government that “crossed the red line that separated it from totalitarian regimes.” The Catalan president maintained that the region would not “return to times past.”

In 2014, Catalonians informally held a plebiscite for independence, which passed with 80 percent voting in favor, yet turnout was only 37 percent. The vote was largely symbolic, and officials in Madrid declared that it had no legitimacy. How the referendum early next month will unfold is unclear, yet it will likely be different from 2014.

Madrid Strikes Back

Over the past several weeks, national police have arrested Catalan senior officials and others behind this referendum, seized 10 million ballot papers, raided government buildings, and shut down websites that provided information about the referendum. A spokesman for the government in Catalonia compared Madrid’s actions to those of the governments of China, North Korea, and Turkey, maintaining that “no western democracy” could take such moves which constitute an “unlawful repression of the institutions of autonomy of Catalonia.”

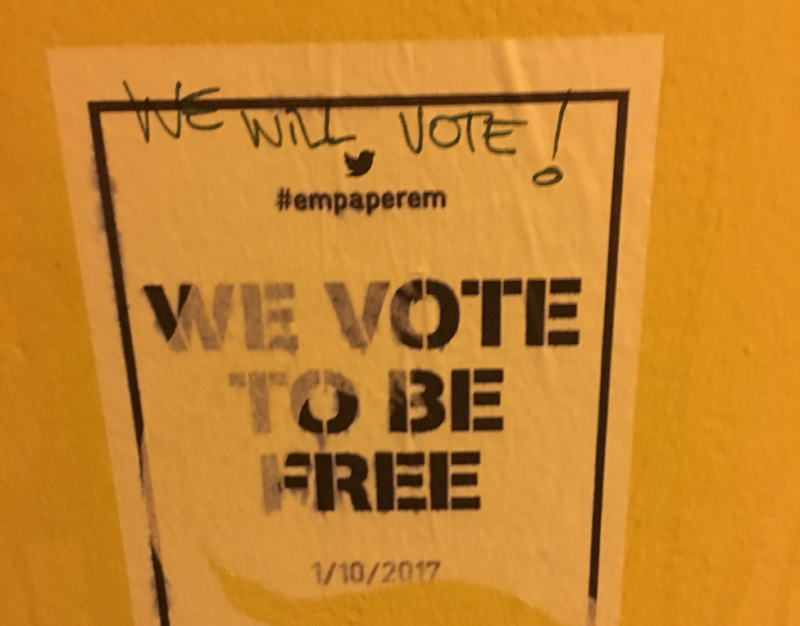

A common argument in favor of the referendum is that the vote is about much more than the idea of Catalonian independence and that holding the referendum is about democracy and protection of political rights and civil liberties. These arrests, raids, and acts of online censorship have led to largescale protests with up to 40,000 people taking to the streets of Barcelona throughout this month.

Officials in Madrid have vowed to take legal action against all who play any role in organizing the referendum, ferrying in 4,000 members of Spain’s Guardia Civil into Barcelona earlier this month. They have received orders to take control of polling booths set up for the independence vote on October 1. It’s not clear if the Guardia Civil will physically prevent voters from entering booths, and if so how the Catalonians who are determined to hold their independence referendum would respond.

Despite threats from Spain’s central authorities, Puigdemont condemned the country’s central government for taking “repressive and intolerant” actions and vowed that the referendum would go ahead. The Mossos d‘Esquadra (the regional police) have received orders from Catalonia’s prosecutor to protect and control voting booths in the region on September 30. Although pro-independence movements in Catalonia have remained peaceful over the years, a massive police presence and the possibility of the central government invoking emergency powers to take administrative control of Catalonia might push tensions past a breaking point.

If the Referendum Passes

The Catalan parliament has stated that it will unilaterally declare national independence within 48 hours if more than half of the voters choose yes—regardless of how many turn out to vote. Under such circumstances, Spain would face its gravest constitutional since the crushed coup of 1981.

If Catalonia made such a unilateral declaration of independence, Rajoy’s government could cite article 155 of the Spanish constitution (which no Spanish government has done before) as the legal basis for Madrid taking administrative control of Catalonia. The government in Catalonia has increased its staff at its new tax authority, a strong suggestion that the local authorities are preparing for a future in which they begin collecting taxes that previously went to the capital of Spain. If Spain’s central government uses force to demonstrate that the autonomous region cannot violate the constitution, Rajoy could add more fuel to Catalans’ drive for independence, which could backfire against Madrid.

The prospects for an independent Catalan state in northeastern Spain raises many questions about Spain’s future and that of Catalonia. Would the United Nations recognize Catalonia as an independent nation? Would the European Union make Catalonia the bloc’s newest member? How would the division of Spain impact the rest of Europe and the United States? If officials in Madrid use a heavy hand to stop the vote, how would the international community react?

International Response

Other European powers have backed Madrid, but to a limited extent, especially following the raids and arrests throughout Catalonia this month. Jean-Claude Juncker, the EU’s chief executive, emphasized that the “Prodi doctrine” will determine if/when an independent Catalonian state could ever join the EU. The 13-year-old doctrine mandates that any breakaway state would be required to leave the EU and could only join later if its independence was achieved without violating the constitutional law of the EU member from which it separated.

For now, it seems that Madrid’s Western allies are playing it careful. Whereas US President Donald Trump took the same position as his predecessor did, expressing his support for a unified Spain, the State Department appeared to be hedging Washington’s bets by stating that the U.S. would work with any government(s) that emerges from the October 1 referendum. Also, although Trump said that he didn’t think most in Catalonia would vote in favor of separating from Spain, he did not condemn the referendum as illegal.

Germany’s Chancellor Angela Merkel avoided taking sides, calling the question about Catalonia’s upcoming referendum an “internal Spanish matter,” and emphasizing that Berlin’s key interest in Spain’s future was about the country’s “stability,” rather than its cohesion or territorial integrity.

If Catalonia were to become an independent state, it would be one of Europe’s wealthiest countries (with an economy carrying about the same output level as Portugal’s) and presumably it would have positive and cooperative relations with all Western countries currently allied with Spain. Although the rest of Spain would lose economically if Catalonia separated and the country would possess less influence regionally and internationally without Barcelona, it is unclear what other EU members, chiefly France and Germany, have at stake economically regarding Catalonian independence. Given Barcelona’s important economic role as a major Mediterranean port city and a hub of tourism, it is doubtful that any European country or the U.S. would hesitate from embracing an independent state in Catalonia. That said, since Spain is not the only EU member with issues stemming from separatism, other governments in Europe must be gravely concerned about the precedent established by one of Spain’s regions unilaterally declaring independence.

In any event, the declaration of an independent Republic of Catalan would force Rajoy’s government into a major battle for its own legitimacy given its inability to avert a territorial crisis. On October 1, what is at stake in nothing short of Spain’s cohesion as a nation that, according to the Spanish constitution, is indivisible. After October 1, the people of Spain and the rest of Europe can hope that the Madrid-Catalonia standoff is settled peacefully. How much coercion Rajoy’s government applies to push for its desired outcome in Catalonia will likely be a major indicator of how events in Spain unfold.

Photo: Catalan referendum poster (Giorgio Cafiero). An earlier version of this article inadvertently placed Catalonia in northwestern Spain.

Catalonian nationalism is good and Spanish nationalism is bad? You are a dictator for trying to deny the right to speak of some people so you can favor others.

Catalonia is in northeastern Spain, not northwestern Spain