by Larry Garber

The December 26 run-off elections in Liberia surprised many international observers. After a problematic first round and a lengthy post-election dispute process, the election was extremely well administered and peacefully conducted. Despite the challenges posed by poor infrastructure, the results were quickly tallied and the winner announced within 48 hours of the polls closing. And notwithstanding a series of pre-election complaints regarding the partisanship of the National Election Commission (NEC), the losing presidential candidate quickly accepted the results and planning is now underway for a smooth transition on January 22 from one democratically elected president to another.

The success of Liberia’s elections was personal for me. In 1985, I watched from afar as an election was stolen and the United States, Liberia’s long-time ally, ignored the theft and sought to continue business as usual. As Liberia’s 2009 Truth and Reconciliation Commission stated, after those elections, the United States “failed to withdraw their support for [President Samuel] Doe and this shocked many Liberians. Despite condemnations from Congress regarding the conduct of the 1985 elections, the Reagan administration continued to recognize Doe as the legitimate leader of Liberia and continued to provide him with support.” Many Liberians also hold the United States at least partly responsible for allowing the country to disintegrate into a brutal civil war that lasted for almost 13 years. Today however, the United States, together with others in the international community, is heavily invested in Liberia, including in support of the still evolving democratic processes.

I returned to Liberia to monitor last month’s election. Visiting polling stations around Monrovia, Liberia’s capital, on election day, I immediately observed the continuing challenges of daily life. Polling occurred in classrooms that had the most rudimentary infrastructure and often no power, requiring the counting of ballots by battery-powered lanterns. The situation in rural areas was even more basic, with polling places situated miles from the nearest roads, making the distribution of polling materials and the timely opening of polling sites a distinct challenge. And yet as all the international observers reported, five polling officials, four party agents, and at least one security official were present at each of the country’s more than 5,000 polling places.

The administrative savvy demonstrated by the election and security operations associated with the successful run-off begs the question of whether this experience can be transferred to addressing Liberia’s many development challenges. The numbers are indeed staggering: life expectancy of only 62 years; more than 80 percent of the population living in extreme poverty; an adult literacy rate of 47 percent; fewer than 700 miles of paved roads in a country the size of Tennessee; and electricity available for less than 10 percent of the country. Despite years of advice from the best development experts, determining where to begin in Liberia is no easy matter.

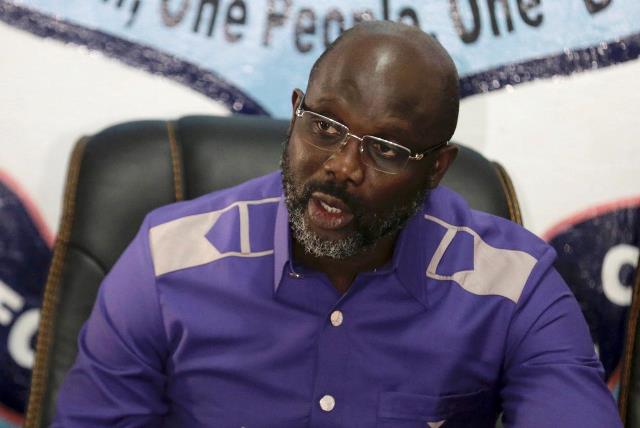

The newly elected leadership team of George Weah, a former star soccer player in Europe during the 1990s, and Jewel Howard-Taylor, a lawyer by training and a senator for the past 12 years (and the former wife of ex-president and convicted war criminal Charles Taylor), has promised “change” but has been rather vague in describing exactly how this will achieved. Their party holds less than 30 percent of the seats in the House of Representatives, which was elected in October, and two-thirds of whose members were elected for the first time. The numbers of incumbents defeated in the legislative elections suggest the sophistication of an electorate that is interested in results.

Weah and Howard-Taylor are counting on the same type of coordinated international effort that was evident as part of the election support to continue with respect to the broader development agenda. The international effort included major investments in election infrastructure that permitted the production of a new voter registration roll and the printing of new voter ID cards for all eligible voters. Problems identified with both the registration roll and the ID cards during the first round of elections served as the basis for the electoral complaints filed by various parties.

Ultimately, in contrast to its Kenyan counterpart, the Liberian Supreme Court decided that the totality of the problems did not require a repeat of the election and ordered the National Election Commission (NEC) to clean up the rolls prior to the run-off. A team from the Economic Community of West African States (ECOWAS) assisted the NEC in removing duplicate voter identification numbers from the roll, reissuing cards with new unique identification numbers as appropriate, and undertaking additional manual de-duplication of names on the rolls.

Perhaps the most significant international investment in the election process was for the deployment of international observer missions. The African Union, ECOWAS, European Union, National Democratic Institute, and the Carter Center all fielded short-term observer teams for both round of elections, as well as maintaining smaller teams to examine other aspects of the electoral process. Particularly impressive is the role that former freely elected African leaders now play in the effort to promote democracy in neighboring countries: Ghana’s former President John Mahama led the ECOWAS team, Nigeria’s former President Goodluck Jonathan led NDI’s observer delegation, and Senegal’s former Prime Minister Aminata Touré led the Carter Center team. Although the presence of five distinct delegations may have been observer overkill for a small country, each of the sponsoring institutions has been active for extended periods in supporting Liberia’s evolving democratic institutions and their presence signaled a commitment to remain engaged with their respective efforts.

Post-election Liberia offers an interesting test case for the Trump administration. Even before the run-off was complete, the Department of State had authorized funds to assist with the transition planning. And a robust development assistance program has been in place for some time. However, there’s now an opportunity to apply the elements that made the election a success—holistic planning, broad engagement of the population, timely and scale appropriate investments, decisive decision-making by constitutionally-authorized institutions, constant monitoring of outcomes and coordinated efforts by the international community—to the enormous development challenges facing Liberia.

Larry Garber, an international election expert, observed the Liberian run-off elections with a delegation organized by the National Democratic Institute. Photo: George Weah.