by William Hartung

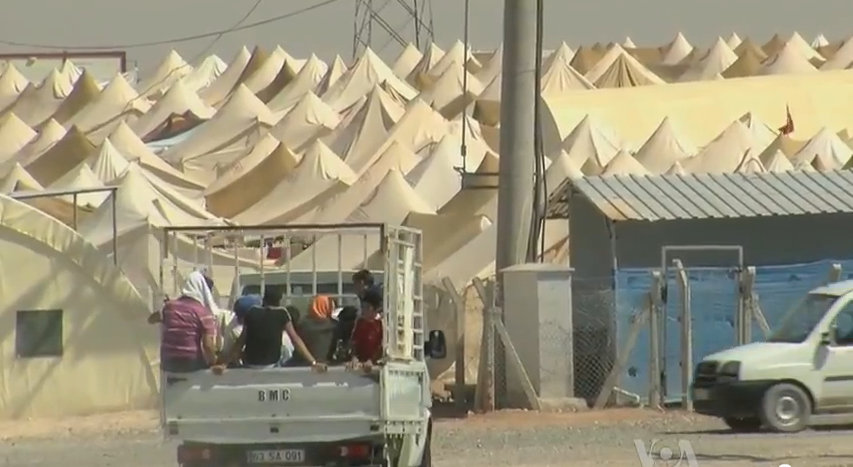

Few would argue that the world faces a refugee crisis, but not nearly enough is being done to prevent the creation of new refugees or to help those already displaced from their homes. And while statistics can’t fully capture the human suffering involved, it is sobering to learn that the United Nations reports that over 20 million people have been driven from their countries by war, famine, and poverty, with over 40 million more displaced within their own nations.

There is no science involved in figuring out which factors have the most impact on creating the massive flow of refugees that characterize our world, but one thing is clear–war is a major driver of this humanitarian catastrophe. According to the most recent report by the United Nations refugee agency, more than half of the world’s refugees come from three countries that have been the sites of brutal, multi-year conflicts–Syria, Afghanistan, and South Sudan. War is a direct cause of displacement, but it also increases the risks of famine and disease, which also play a major role in driving people from their home communities.

There is plenty of blame to go around for this dismal state of affairs, from the role of Russia and Iran in propping up the murderous Assad regime in Syria, to internal factions in South Sudan, to the Taliban and the U.S.-backed government in Afghanistan. But this article will focus on the role of the United States, not because it is the worst or only culprit, but because there is–or should be–a better chance at changing misguided policies in a democracy than there is in undemocratic regimes.

The United States Role In The Global Refugee Crisis

The United States is currently involved in eight wars–in Iraq, Syria, Libya, Somalia, Niger, Yemen, Afghanistan, and Pakistan. Together, these conflicts have generated millions of refugees, and displaced millions more within their home countries. U.S. military intervention isn’t necessarily the primary cause of the refugee flow in all cases, but it has generally made matters worse–in some cases much worse. If the United States wants to make a constructive contribution to stemming worldwide refugee flows, we need to rethink our all-war-all-the-time foreign policy.

So far, Donald Trump hasn’t started any new wars, but his administration has doubled down on the wars he inherited, dropping more bombs, launching more drone strikes, and causing more civilian casualties. We can only hope that Trump and his new “war cabinet” of John Bolton and Mike Pompeo (yet to be confirmed as Trump’s Secretary of State) don’t get us involved in yet another conflict, in Iran, North Korea, or elsewhere.

The recent U.S., French, and U.K. cruise missile strikes on Syria are a case in point of what’s wrong with the current foreign policies of the United States and its allies. The Assad regime’s chemical attacks on its own population are horrific, but raining more bombs on Syria–however accurate the strikes may or may not be–is no solution to the suffering of the Syrian people. But there was a groundswell of support in the media and some segments of the public to “do something” about Assad’s attack. And as Emma Ashford of the Cato Institute noted in an op-ed in the New York Times, all too often “doing something” is defined narrowly to mean taking military action. According to this militarized logic, diplomacy–which is practically a dirty word in Trump World–doesn’t count. This is odd given the utter failure of the United States’ post-9/11 wars to achieve their stated objectives, but old, bad ideas die hard.

If President Trump were truly concerned with the fate of the Syrian people, there are a number of non-military steps that would do far more to help them than lobbing yet more bombs and missiles at their country. For starters, he could agree to admit significant numbers of Syrian refugees into the United States, rather than blocking virtually all of them–according to a recent report on NPR, the Trump administration has let in a grand total of 11 Syrian refugees this year.

The United States could also increase its funding for U.N. humanitarian efforts on behalf of refugees. There’s plenty of money to be had if the administration chose to spend even a little bit less on the Pentagon and related agencies, which will receive $700 billion this year, and more on non-military tools of foreign policy.

The Role Of The Arms Trade In Fueling Conflict And Displacement

The global arms trade is on the rise, and the United States is by far the dominant supplier, as has been the case for 25 of the last 26 years. And the United States has supplied weapons to over 60 countries involved in conflicts large and small. Even more impressive–if that’s the right word for it–is the Cato Institute’s finding that the U.S. has provided weaponry to 85% of the world’s nations during this century. This is not a recipe for peace or conflict reduction.

The most egregious case of the use and abuse of U.S.-supplied arms is the U.S.-backed, Saudi-led war in Yemen, which has killed thousands of civilians through Saudi air strikes and put millions at risk of famine and fatal disease due to a blockade that has limited the availability of food, medicine, and clean water. Most of Yemen’s displaced people are still in the country, as the Saudi-led coalition has made it extremely difficult for them to leave.

An unintended consequence of U.S. arms sales that has also contributed greatly to the refugee crisis is the leakage of U.S.-supplied arms to non-state actors like ISIS and the Taliban, and the wide dispersal of Libya arms caches throughout North Africa after the overthrow of the Qaddafi regime.

What Is To Be Done?

Reducing conflict and its crushing human consequences will not be easy. But the first step is putting more energy into resolving conflicts than is currently being poured into fighting them with bombs and troops or fueling them through weapons trafficking. As noted above, opening our doors to many more refugees and generously funding humanitarian aid efforts should be another pillar of a new approach.

Stopping wars will require beefing up diplomacy, not proposing deep cuts in the State Department, denigrating career diplomats, and failing to even appoint ambassadors to key nations. It will also require working closely with allies and listening to the concerns of current and potential adversaries, as was done in the negotiation of the landmark deal to curb Iran’s nuclear weapons capability. And finally, we need a new arms transfer policy that curbs shipments to human rights abusers and war zones–not through lip service, but through actual reductions in sales.

All of the above may seem like a pipe dream under the “America First” approach of the current administration. But administrations change, as does Congress, and if large numbers of people don’t demand an end to our policy of perpetual war and a resurgence of diplomacy, it will never happen. It’s time to get to work towards building a better world, however long it may take to get there.

This piece first appeared on Medium.

You are absolutely right with your analysis. The far more interesting question is why nothing will change. I think the foreign policy of the US (and not only the US) is defined by interest groups as you mentioned in your book. They determine the preferences of foreign policy not the people. Sorry to say that. The „Military-Industrial Complex“ will not allow another policy.