by John Feffer

Right-wing populists are all the rage these days. Donald Trump and his spleen control the White House, while his counterparts have taken over in Italy, Hungary, Poland, Colombia, India, and elsewhere. Steve Bannon, Trump’s former Svengali, hopes to inspire a worldwide revolution of nationalism-inflected right-wing extremism.

But what about left-wing populists? Bernie Sanders made an epic run at the presidency in 2016 only to fall short. Jeremy Corbyn likewise had a good showing in the last British elections, but he too remains distant from power.

Left-wing populism is also popular among certain political theorists, most notably the Belgian thinker Chantal Mouffe whose latest book champions an electoral strategy that appeals to disgruntled workers.

The major problem with left populism, however, is that it tends in practice toward autocracy. The examples of existing left populism — Venezuela, Nicaragua, and (to a lesser extent) the Philippines — are embarrassments to anyone who cares deeply about democracy and human rights.

In Venezuela, Nicolas Maduro presides over an economic collapse that has hit the poor the hardest. Corruption, human rights abuses, narcotrafficking: Venezuela under Maduro is a failed state masquerading as left-wing populism. In Nicaragua, former Sandinista Daniel Ortega has been gradually concentrating power in the hands of his presidency, his family, and his cronies, and he now faces a civil insurrection demanding “justice for those who have died at the government’s hand and a return to democratic governance,” as Rebecca Gordon wrote for TomDispatch. In the Philippines, Rodrigo Duterte also claims to be a leftist but has launched a catastrophic drug war, which has left more than 12,000 people dead, and declared open season on human rights advocates.

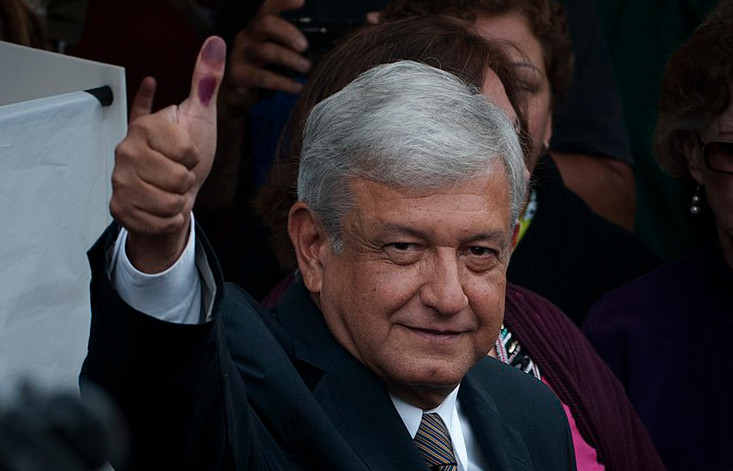

Fortunately another wave of left-wing populists, considerably more democratic than what’s on offer elsewhere, has been building. The most prominent of these would-be leaders, Andres Manuel Lopez Obrador (AMLO), has an excellent chance of winning the presidential election in Mexico this Sunday.

Can these global Bernies turn the Trump tide?

Toward a Definition

Left-wing populism has two legs, political and economic, and it is clothed in a particular style.

The economic leg is rather old-fashioned. Left populists appeal to those left behind by the forces of globalization by offering a program of government subsidies, job-creation projects, and fair trade. It’s an approach predicated on fairness — that the wealthier members of society should invest in the common good and in raising the living standards of the country’s most vulnerable.

Such a program is inspired, more or less, by a social democratic vision (or, if you prefer, a democratic socialist one). But populists also recognize that social democrats, and in some cases self-described socialists as well, have pushed the same austerity programs that their colleagues further to the right have championed. Because of their internationalist orientation, socialists have also been leery of appeals to nationalism (or, if you prefer, patriotism). So, their economic programs have a touch of globalism to them, whether in the form of worker solidarity across borders or transnational solutions to the global ecological crisis.

Left populists, on the other hand, appeal to the people of their own country first and foremost. They are leery of free trade deals, they are often close to unions, and they want to encourage the domestic consumption of industrial and agricultural production. It’s “America First” without the racism. It’s a variant of Bernie Sanders’s economic vision. It’s the mexicanismo of AMLO.

Politically, left populists square off against the elite. Members of the political elite are handy targets, for they can always be accused of being “out of touch.” In many cases, too, they are corrupt, and a broadside against the “swamp” is always a crowd-pleaser.

In almost every case, of course, the anti-elitist is a member of the elite as well, or else they wouldn’t have had the money, the political position, or the cultural notoriety to get on the ballot and attract sufficient votes. The political fortunes of these inside-outsiders rise and fall based on the credibility of their impersonation of a person “of the people.”

What distinguishes left populists from the left more generally is their focus on economics rather than identity politics. The left has worked hard to create a “rainbow coalition.” Left populists, while not exactly anti-diversity, prefer to emphasize pocketbook issues. They believe that the sharp economic divide between the haves and the have-nots — the 99 percent versus the 1 percent — provides a more useful way of contesting elections in the adversarial environment of Western politics. It also takes advantage of the swelling resentment of those who have been steamrollered by globalization.

Stylistically, left populists deploy a “common touch” by rolling up their sleeves, using simple and emotional language, and steering clear of the dreary policy nostrums of wannabe wonks. They do not go high when others go low. They are combative and sometimes even vulgar. You want these populists in your corner in a barroom fight.

And that’s, in essence, what politics has always been.

Left Populism in Motion

In Europe, the two most successful left populist movements have been Syriza in Greece and Podemos in Spain.

In Greece, the Coalition of the Radical Left (Syriza) has been in power for three years. It has guided the country through one of its most difficult economic periods as the economy shrank by 26 percent. Greece hasn’t yet caught up to where it was in 2007 — and won’t for another decade, according to the International Monetary Fund.

Instead of embracing default and leaving the euro zone, Syriza negotiated the best deal it thought it could get from the European Union and the banks. But the population is still 23 percent poorer than it was before the crisis. Syriza has made any number of political compromises to stay in power, including an alliance with a far-right party. Having started as a populist party, it has governed largely as a conventional political force.

Podemos (We Can) began as the political expression of the indignados-led social movement that took to the streets in Spain in 2011 to protest the government’s austerity policies. Started in 2014, Podemos quickly became the country’s second largest party in terms of membership. But it has lost groundsince then, largely because of its ambivalent position on Catalan independence. In a sign of its political irrelevance, the new government formed by Spanish Socialist Pedro Sanchez snubbed Podemos entirely.

The electoral failures of Podemos are indicative of the political fortunes of left populists more generally. In country after country, they’ve gone up against conventional parties and lost. The French Bernie Sanders, Jean-Luc Melenchon, failed to make it into a run-off in the presidential elections against Emmanuel Macron. South Korea’s Bernie Sanders, Lee Jae-Myung, made little headway in the Korean presidential elections last year. The Canadian Bernie Sanders, Niki Ashton, wound up third in the race to take over the leadership of the New Democratic Party. Iceland’s Bernie Sanders, Birgitta Jonsdottir, failed to lead her Pirate Party to victory in the small island nation.

In the last three cases, some very good leftish politicians have instead triumphed: Moon Jae-in in South Korea, Katrin Jacobsdottir in Iceland, and Jagmeet Singh of the New Democratic Party in Canada. Left populism generates a good deal of excitement and press attention, but so far it hasn’t won elections. Nor, in the case of Syriza, has it governed in unconventional ways.

But that might change, and soon.

AMLO and the Transformation of Mexico

Third time’s the charm, if the polls are correct.

Andres Manuel Lopez Obrador (AMLO) has already run twice for the Mexican presidency and lost both times rather handily (though he claimed that the last election was rigged, which is entirely plausible in Mexico). This time around, he is leading the polls by a large margin. His nearest competitor, the candidate from the conservative PAN, is nearly 18 points behind.

There are several reasons for AMLO’s reversal in fortune. Corruption is a huge issue in Mexico, and the circle around current President Enrique Pena Nieto is awash in it. AMLO’s chief rival, Ricardo Anaya of PAN, has also run as an anti-corruption candidate. But then he became embroiled in a money-laundering scandal largely cooked up by the government. Still, the affair has undermined Anaya’s credibility.

Then there’s the Mexican economy, which has experienced only anemic growth under Pena Nieto. The rich, however, have done well, and it’s estimated that 70 percent of Mexico City’s police force work on behalf of private interests, like guarding banks. Meanwhile, the government spends a mere 7.5 percentof GDP on social programs (compared to 19 percent for the U.S. and 11.2 percent for Chile). Already a polarized country, Mexico has only become more so in recent years.

The last element in the triple whammy has been the explosive expansion of narco-trafficking and the murders that have accompanied it. In 2017, Mexico suffered 27,000 murders. With 11 journalists dead last year, Mexico was the second most dangerous country for reporters after Syria. The government seems incapable of reining in the drug cartels.

Finally, it doesn’t hurt AMLO that Donald Trump has directed an endless stream of racist invective at his country. Pena Nieto has certainly criticized the U.S. president, but early on he welcomed the Republican presidential candidate to Mexico and shook his hand. That sealed Pena Nieto’s fate as Mexico’s “most hated man” and provided AMLO with the opportunity to promote himself as a far more resolute defender of Mexican dignity.

Although very clearly opposed to the U.S. president, AMLO shares some stylistic characteristics with Trump. For instance, AMLO speaks very simply, as Trump does, and even makes up cutting diminutives for his opponents. The Mexican candidate takes aim at the elite — though as a political insider he is even more a member of the elite than Trump ever was — and bills himself as the anti-corruption alternative.

In other ways, though, AMLO is definitely the Bernie Sanders of Mexico. He was the mayor of a city, like Sanders, though Mexico City is quite a bit bigger than Burlington, Vermont. He governed in the same pragmatic way that Bernie did, often partnering with the business community. As Jon Lee Anderson writes in The New Yorker, AMLO “succeeded in creating a pension fund for elderly residents, expanding highways to ease congestion, and devising a public-private scheme, with the telecommunications magnate Carlos Slim, to restore the historic downtown.” The latter is reminiscent of Sanders’s deals to revive Burlington’s waterfront.

To win the more conservative north, AMLO has partnered with wealthy businessman Alfonso Romo, who is also slated to be his chief of staff. The proposals designed to win favor from the business community include, as Anderson reports, “establishing a thirty-kilometer duty-free zone along the entire northern border, and lowering taxes for companies, both Mexican and American, that set up factories there. He also offered government patronage, vowing to complete an unfinished dam project in Sinaloa and to provide agricultural subsidies.”

Given these pragmatic partnerships, AMLO might follow the lead of Syriza and govern more like a conventional politician than his campaign suggests. That would certainly be a relief to Mexico’s political and economic elite, which is practically quaking in its boots at the prospect of AMLO taking over.

But there’s a good possibility that AMLO, like Trump, will follow a more surprising trajectory once in power. In his bid to clean the Augean stables of Mexican politics, he has “vowed to slash pensions for former presidents and eliminate private insurance for elected officials. He has promised to cut his own salary in half, to sell Peña Nieto’s presidential jet, and not live in Mexico’s presidential palace.”

On the economic side, AMLO has promised to increase the minimum wage, support farmers so that they don’t feel that they must seek a better life across the border, and possibly renationalize the oil sector. He wants to increase government funding for education and pensions, which will appeal to old and young alike.

The urgency of AMLO’s campaign can be measured by the vitriol of those who attack him, including former foreign minister Jorge Castenada. “People don’t go to his rallies or listen or believe in him because he speaks intelligently or eloquently or charismatically,” the former leftist intellectual says. “They go because of what he represents — the end of the system.”

AMLO indeed represents the end of the system, a system that has impoverished so many and permitted narco-traffickers to operate with impunity. Mexicans are desperate for something different. Only AMLO promises a break with the present — even as he emphasizes continuity with Mexico’s more glorious past.

AMLO is likely to shake things up in Mexico. But will he also shock left populism back into life around the world?

His electoral victory, but more importantly his new style of governance, could inspire politicians elsewhere in Latin America, Europe, and Asia to offer a more popular alternative to right-wing populism. That would be quite a gift that Mexico gives to the world, one almost as important as chocolate and chili peppers.