by Sam Bhutia

Cynics often ask if China’s flagship Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) has increased trade between China and its neighbors, or if it threatens to trap participants in debt. There are myriad reasons why countries sign on to the BRI. Some seek to plug gaps in domestic infrastructure, some to improve global trade ties, and some because China, with its population of 1.4 billion, is an attractive market for their goods.

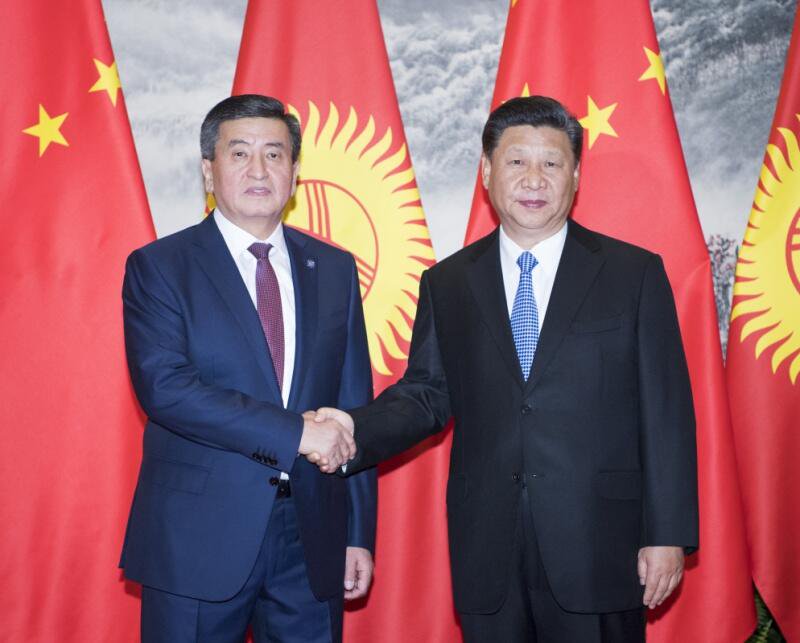

Central Asia shares a long border with China. Located between China and Western markets, the region has been key to the BRI vision since Xi Jinping unveiled it in Kazakhstan in 2013. China pitches the BRI as a quick road to infrastructure development, integration, and economic growth.

But what about trade? Has trade with China risen in sync? The answer is yes – for some.

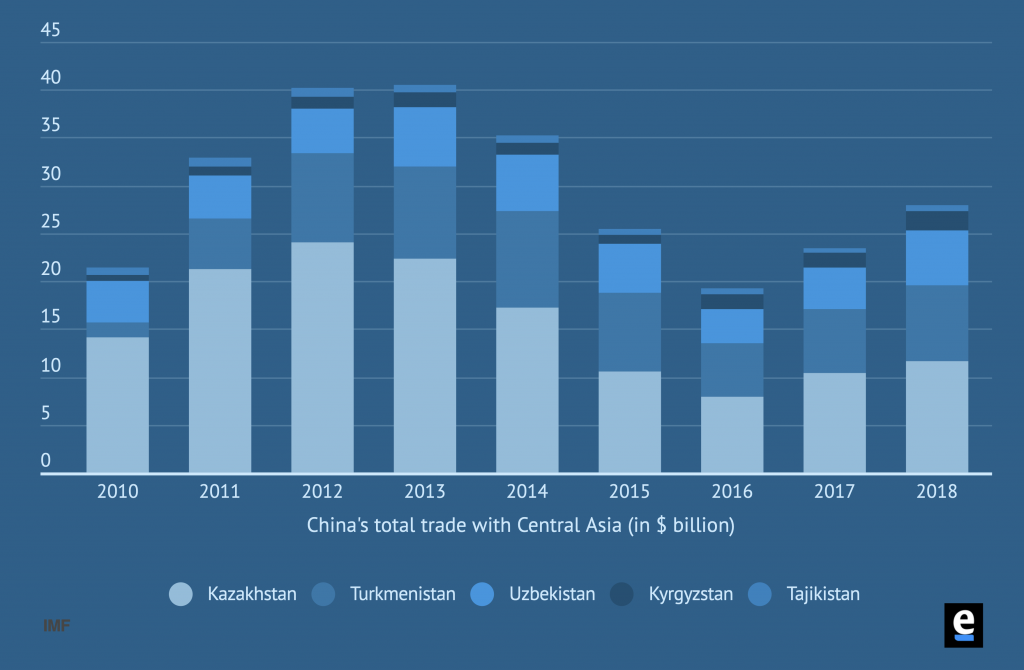

In 2010 China’s trade turnover with Central Asia stood at just over $21 billion, according to IMF data, with Kazakhstan and Turkmenistan accounting for most of the total. This does not come as a huge surprise owing to China’s insatiable (and rising) demand for oil, gas and minerals – products Kazakhstan and Turkmenistan have in abundance. Total regional trade turnover with China peaked at $40.5 billion in 2013, fell to just over $19 billion by 2016, and reached $27.2 billion last year.

Looking at trade in dollar terms (rather than by volume) can be slightly misleading, however, since global energy prices swing wildly. Most of the contraction in total trade turnover since 2013 can be attributed to the dramatic slump in global oil prices, which fell from about $110 a barrel in August 2013 to under $50 in early 2015 to over $70 in mid-2018. Another factor was the slump in import demand from Central Asia owing to the regional slowdown in 2014-2016 after the collapse in oil prices punished Russia’s economy (and trickled down throughout the former Soviet Union).

Once we consider these factors, China’s trade with Central Asia appears only to be rising along with the BRI.

But not for everyone.

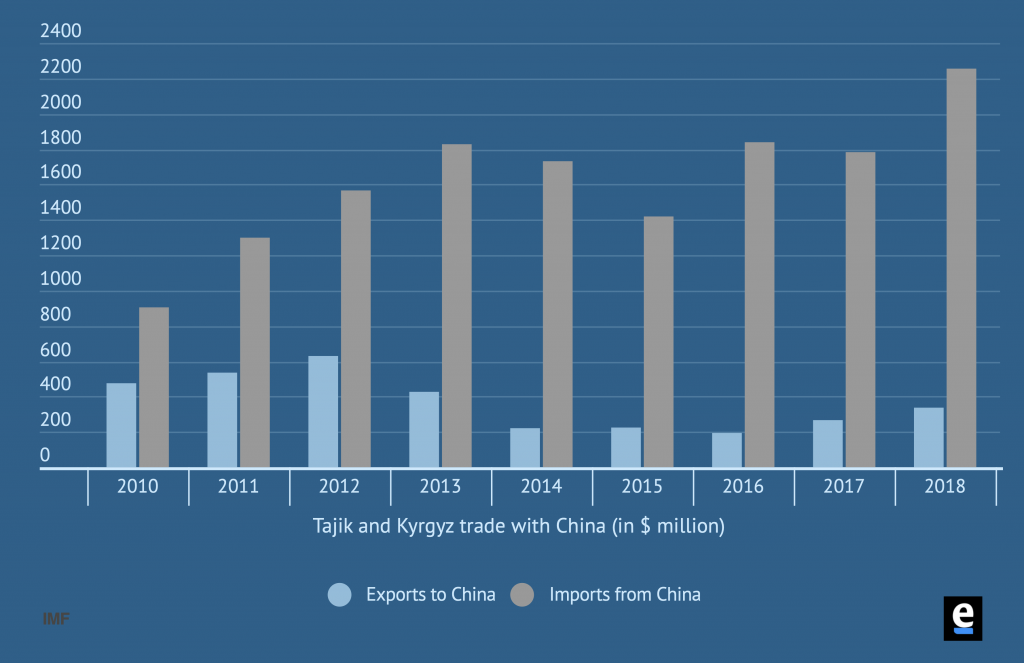

Kyrgyzstan and Tajikistan – the smallest, poorest and most Beijing-dependent economies in Central Asia – have seen their exports to China fall since 2010. Combined, the two exported $475 million of goods to China in 2010; by 2018 these were valued at $337 million. Over the same period, imports from China rose by $1.4 billion. (By comparison, Turkmenistan’s exports to China increased by $6.8 billion in the same period.)

The BRI effect has been one-sided for Kyrgyzstan and Tajikistan, despite China’s considerable market size and proximity.

There is nothing inherently wrong in Kyrgyzstan and Tajikistan importing more from China than they sell. But the fact that trade is so one-sided should concern Bishkek and Dushanbe. Last year, Tajikistan paid a Chinese company building a power plant with a gold mine; a few years earlier it swapped Beijing some land for debt. With widening trade imbalances, such deals could be a sign of trade ties to come.

China, according to my knowledge is an intrinsic and gifted merchant society. The effect with the extension of its exchanges on neighbours shores has been one of shared growth. A good example is Singapore and also everywhere where there’s a significant minority of Chinese ascent, be it in Indonesia, Malaysia, Vietnam or the Filipinas.

Of course there’re always those ‘analysts’ who’ll find ‘debt’ as the Chines mark in Central Asia and in Africa. Aren’t they looking instead with tainted glasses its own history of conquests and colonial servitude?