by Eldar Mamedov

On March 31, the Ahlulbayt Foundation Spain hosted a photo exhibition in Madrid dedicated to the fight of the Iraqi army and popular mobilization forces—often simplistically referred to in the West as the “Shiite militias”—against the so-called Islamic State (ISIS or IS). The Ahlulbayt Foundation represents one of the foremost spiritual authorities of Shia Islam, the Iraq-based Ayatollah Ali Sistani. The photo exhibition is the latest in a series of efforts that the foundation has undertaken since its inception in Madrid in 2015 to reach out to Christian and Sunni Muslim clerics, as well as secular intellectuals, to debate issues as diverse as religion, environment, terrorism, and migration.

This increased Shia visibility, however, has triggered a reaction from Salafist circles that see in these activities a nefarious Iranian plot to promote Tehran’s political agenda. It’s also only one example of how the Saudi-Iranian rivalry has reached beyond the Middle East and into Europe.

This is a relatively new and underreported development. Ignacio Cembrero, the former Maghreb correspondent for the major Spanish newspaper El País, made an important contribution to this issue in his new book The Spain of Allah (La España de Alá). The book, which provides a dispassionate and data-based analysis of the situation of Muslims in Spain, has a chapter dedicated to the implications of the Saudi-Iranian rivalry in the country, with useful lessons for the rest of Europe.

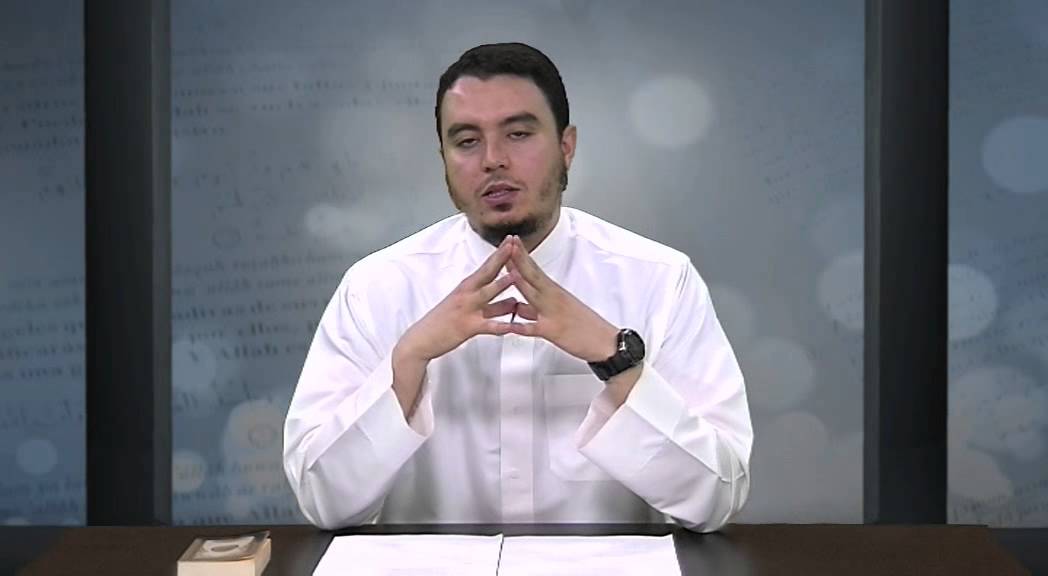

Cembrero describes, for instance, the TV competition between Riyadh and Tehran, which plays out in the language of Cervantes. Cordoba Internacional TV is one of the media outlets at the disposal of the Saudi foundation Message of Islam that reportedly has close ties with the House of Saud and is devoted to the worldwide spread of Wahhabism. Reacting to the opening of the Ahlulbayt Foundation in Madrid, the channel’s chief religious authority Mohamed Said Alilech, an imam of a mosque in Madrid and also the president of the Association of Young Muslims of Spain, decried what he saw as the radical incompatibility between Shia beliefs and the basic tenets of the Islamic faith. In doing so, he resorted to a favorite Wahhabi tactic of over-emphasizing the most visible aspects of Shiism that set it apart from other interpretations of Islam, while denigrating its adherents as depraved, fanatical, and dangerous.

Thus, Alilech derided the Shia concept of temporary marriage as nothing but legalized adultery and ridiculed the Ashura processions honoring the slain Imam Hussein as little more than barbarism. He also faulted Shiism for absorbing elements of other faiths, such as Zoroastrianism, Christianity, and Judaism. In perhaps his most definitive indictment, he claimed that the founder of one of the “most radical” Shia currents, Ismailis, was a crypto-Jew. Finally, he argued that no dialogue is possible with the Shias because they conceal their true intentions—takiyye—which invariably harms “true Muslims.” Shias are therefore not real Muslims but mere pawns of Iran’s plots to sow sectarian discord in the Muslim world.

Ironically for someone who advises a channel named after the city of Cordoba, Alilech does not seem to be aware of the major contributions made by Sassanid Iran to Arab Islamic civilization, including that of Cordoba itself. These contributions are well covered in From Persia to Muslim Spain: a History Recovered, a pioneering study by Shojaeddin Shafa, a French-Iranian academic.

Iran’s Spanish-language channel Hispan TV, meanwhile, could not be more different in style and content than Cordoba Internacional. While deeply conservative, Salafi-infused religiosity permeates the latter, the former is explicitly political and radical, reflecting Tehran’s foreign-policy priorities. Its main target is not Spanish Muslims—another reason it’s wrong to conflate Shia religious and Iranian political activism—but the leftist regimes in Latin America and any political forces in the Spanish-speaking world that could be amenable to Tehran’s “anti-imperialist” agenda. For example, Pablo Iglesias, the leader of the leftist Podemos party (currently the third political force in Spain), has run a program on Hispan TV since 2012. In a clever move in 2015 designed to gain the sympathies of Spaniards of different political persuasions, Hispan TV harshly criticized “Moroccan expansionism” targeting the Spanish cities of Ceuta and Melilla while reaffirming that continued Spanish sovereignty was a guarantee of peaceful co-existence and religious freedom. The real target of this invective, however, was not so much Morocco as Saudi Arabia, its close ally.

As Cembrero notes in his book, Spanish authorities have treated Cordoba Internacional with considerably more leniency than Hispan TV. Although Cordoba never experienced any problems with the transmission of its programs to Spain and Latin America, the Spanish government occasionally took Hispan TV off the air, restoring the broadcast fully only after the nuclear deal between the world powers and Iran. But that has not meant the end of problems for everyone associated with the station in Spain.

As the experience of other European countries with a longer history of Muslim immigration suggests, the double standard in treating Saudi and Iranian media outlets may be shortsighted. Certainly, many would object to Hispan TV´s endorsement of radical leftist forces. But Saudi-promoted propaganda may have more noxious effects over the long term on co-existence in Europe. Although Cordoba´s Alilech is careful not to condone violence, the kind of anti-Shia prejudice he and his ilk spread could well inspire radical and violent groups. In 2012, radical Salafists killed the imam of a Shia mosque in Belgium. In 2015, adherents of the Deobandi school—a South Asian variety of Salafism— reportedly vandalized a Shia mosque in Bradford, UK. According to the Shia Rights Watch, a Washington DC-based advocacy group, Shias in UK feel increasingly insecure.

Hate speech comes not only from the European far right but also from within intolerant segments of the Islamic community. As Cembrero suggests, in order to foster a tolerant and open-minded Islam in Europe, it is essential to challenge the Saudi promotion of Wahhabism.

This article reflects the personal views of the author and not necessarily the opinions of the European Parliament. Photo: Mohamed Said Alilech.