by Charles Naas

The spate of immediate reactions to the nuclear agreement between Iran and the six negotiators (the US, France, Great Britain, Germany, Russia and China) has eased somewhat. We can now sit back calmly and assess the nuclear agreement.

The first conclusion is that President Obama has not been hyperbolic in his press interviews: this is a big deal and potentially a game changer in the Middle East political cauldron. Against substantial odds Obama has legitimized his dictum that “the US will engage but we will preserve our capabilities.” Such a phrase may not resonate within the majority political classes on the Hill—like Reagan’s “trust but verify.” But in view of the opposition by the modern-day “know nothings” in Congress, it is a low-key reminder that intelligence and patience together with diplomacy can work.

When Obama was initially elected, he could do little with respect to India, Pakistan, and North Korea, each of which already had a number of nuclear weapons. Israel and the United States viewed Iran and its advanced nuclear complex, meanwhile, as another potential nuclear power, a threat to Israeli security, and a possible perpetrator of a nuclear arms race in the Middle East. Obama, like past presidents, is committed to Israeli security, but he has been also dedicated, as he said, to resolving old rivalries and enmities if possible. (Cuba in the South American context is a second example of his intention to clear up past legacies.)

Why should reasonable observers favor the agreement, as it appears a majority of Americans have done? Iran has agreed to a host of limits on its nuclear program, but the key from the Western participants’ point of view is the stringent inspection regime that the International Atomic Energy Agency will implement from the mines through every stage of the enrichment process. The inspectors are highly likely to pick up any changes in that process, particularly any effort to cheat on the terms of the agreement. Iran has protested that it has had no intention or ambition to become a nuclear power, and the long negotiation appears to bear out that claim.

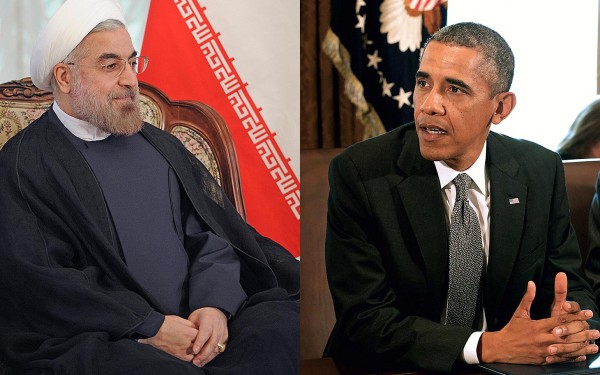

Iran offered a “grand bargain” in 2003, and the election of Presidents Obama and Rouhani has finally opened the door for the two countries to talk with each other, particularly on issues affecting Middle East stability and peace or war. Iran has been seriously burdened by the sanctions—and the near total international agreement to observe those sanctions—and has desired to end its political and diplomatic isolation. Additionally Iran has been willing to delay self-sufficiency in domestic nuclear power.

The US and Iran rapprochement has been hindered since 2003 by the absence of a strong domestic lobby in favor of engagement as well the the attacks by much of the American press. In fact the two countries share a number of strategic interests in Afghanistan, Iraq , and Pakistan. Balancing these similar concerns have been important disagreements such as Syria and the future of Assad, the Hezbollah, and threats to Israel, although in recent months both sides appear to be making efforts to resolve some of these issues. Wise diplomacy can further unfreeze the long bitterness in the relations between the two countries. But patience and a willingness to moderate our desire to tell Iranian leadership how to handle its legal and societal affairs will be essential.

On a larger regional scale, our Middle East policy has for years been stultified by the preeminence of Israel and its informal allies, the Sunni monarchies, that have quite unforgivably been the principal money sources for various Salafist terrorist organizations. Saudi Arabia and the Sunni Emirates have complained about Iran’s alleged arousal of anti-Sunni sentiment but have themselves gone to considerable lengths to promote anti-Shia sentiments and actions to undercut Iranian policies in the area.

So far, the major losers in the agreement are Prime Minister Netanyahu personally and Israel geopolitically. Netanyahu has looked foolish with his contrived fears, his dire warnings nearly every year about when Iran would have a nuclear weapon, and his venture into internal American politics where his efforts have so far failed to translate into preventing the agreement that Obama and Kerry have fostered. He has forfeited his welcome by the current administration, opened the possibility that the US will not automatically veto Palestine’s bids at the UN, and raised the possibility of Washington interfering in Israeli party politics taking his efforts as the example. The US has committed itself to the security of Israel but not to the Likud party.

Nearly all commentators on the subject have correctly stressed that tough negotiations remain to give the “understandings” full and legal form. Indeed, the existence of at least two versions of the interim agreement is worrisome. The timing of the implementation of the various commitments will be fought vigorously, including the most important element, how and when the sanctions against Iran will be lifted. Hard bargaining lies ahead. But having come this far, all participants have invested significant time and effort not to finish their tasks.