by Shervin Malekzadeh

A friend asks me if I’ll write about the latest violence between the United States and Iran. I tell him no: I am out of words. This is an era of machines killing machines, and humans are the ones who suffer the consequences. The lives of 150 men depend on one president’s folly and indecision. What good were the words that came before? What use will there be of the words that follow?

Let’s look instead to the old stories, I tell him, the words learned in school by children and passed down across the generations. These stories are as valuable as any offered by the commentariat.

Stories make intelligible the present, as Washington and Tehran tumble towards an unimaginable future.

Here, for instance, are two parables drawn from Iran’s elementary school curriculum and featured on this site last year, lessons in self-defense and defiance that at the same time contain narratives of restraint, that teach children the importance of discretion and reason as a way to avoid unnecessary violence.

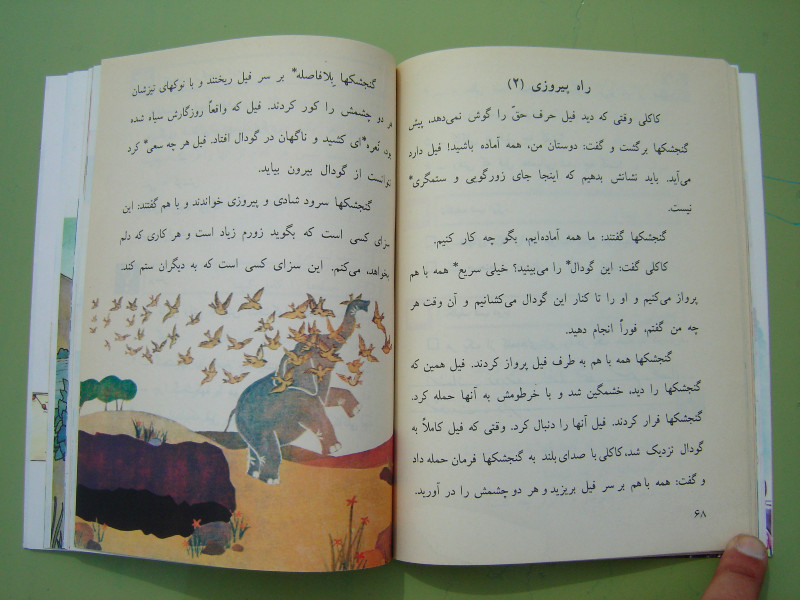

“Way to Victory” is a fable for second graders about a desert flock whose lives are put at risk by a stomping and uncaring elephant. With their nests nearly all destroyed and the remainder of their unhatched eggs in jeopardy, many of the birds are ready to give up and abandon their homes.

But their leader implores his followers to stand up to their tormentor. “This desert is our vatan, our homeland,” he proclaims. “We have to protect our children.”

The other birds are hesitant. “But who can stand up to such a strong elephant?” they ask. “When we all work together,” the leader replies, “we can do anything.”

So, the birds set off together to meet the elephant face to face, to reason with him peacefully, to show him the error of his ways. It does not go well. The elephant loudly rejects their appeals. In possession of unstoppable strength, he trumpets that he can go wherever and do whatever he likes.

Without hesitation, without warning, the birds surround the elephant in concert, swarming and pecking at his eyes without mercy. Blind with arrogance, now made blind in the flesh, the doomed beast tumbles into a ditch, where he meets his demise. It is a gruesome scene with a vivid message for the young reader. When reason and patience fail to protect, violent attack is permitted.

The Importance of Self-Reliance

Self-defense is impossible without self-reliance, however. This is the message of “Cow and Wolf.” Penned during the shah’s reign and carried over by the new regime following the 1979 revolution, the second-grade story is part of a longstanding effort to impress upon young children the importance of standing on one’s own feet and of national strength in an anarchic world.

The lesson introduces the character of Amu Hussein, a simple farmer who wonders if the time has come to relieve his prized cow of its horns, which, although useful, have become a possible safety hazard. Before the farmer can make up his mind, a wolf takes advantage of Amu Hussein’s absence to attack the farm and pin his young daughter Mariam and a tiny calf against a tree. The family cow who nearly lost its horns comes to their rescue in the nick of time, fending off the wolf with ease. Elated by God’s protection and compassion, Amu Hussein marvels at how close he had almost come to disaster. “God,” he thinks to himself, “never does anything without a reason [and so he thanked] God that he had not cut off the cow’s horns.”

Holy intervention and luck were no replacement, however, for prudence and a program of national defense and self-protection, as the questions that appear at the end of the lesson make abundantly clear:

What does the bee use for defense?

What does the dog use for defense?

What does the cat use for defense?

What does the human use for defense?

Trump’s Stories

Then there are the stories that the U.S. president tells. Trump announced on a Friday morning that he had called the planes back, then changed the script on Friday afternoon, telling an interviewer that he had not given the final approval for airstrikes against Iran, that no planes were in the air. With this president, facts and narrative fiction fold into one another until they become indistinguishable, disappearing into a singularity of bullshit.

It’s impossible to know what happened last week: the president’s retelling has rendered indecipherable the full account of what took place over the darkened skies of Hormozgan. But it’s clear that Iranians will fight, and that they will do so because of Iran, because they are Iranians, regardless of who is in control of the country. The nation is at stake, and whether leftist, liberal, or Khomeinist, patriotic defense of the land is the default position, the big idea that holds the country together.

Like Amu Hussein, they will fight alone and on their own. “Members of the generation running the Iranian government and military for the past 30 years came of age during the darkest days of the Iran-Iraq war,” writes the novelist Salar Abdoh in a remarkable essay for The New York Times. “They pushed expertise in asymmetrical warfare and a homegrown mastery of missile, cyber and drone technology because they saw no other way to have a fighting chance in their long struggle against the United States.”

The Power of Stories

In this extraordinary age, lives are saved and lost by the stories that television relates to its most devoted audience member. The circumspect advice of a single cable news host proved decisive last week, dissuading the president from stumbling into what would likely have become the biggest catastrophe of an already disastrous administration.

Tailored for the daily TiVo of executive time, each day is a new performance, an improvisation produced by and for a world class fabulist, both narrator and audience for his own mendacity. One imagines him, remote in hand, frantically rewinding the digital tape, his face inches away as he screams through the scrim of a flat screen.

The stories that those 150 Iranian men carry with them into the dark are the same stories as the men who give the orders, who issue the command to fire missiles into the night sky. What of the rest? What are the stories the Americans bring with them when they deploy? What sustains the drone pilot, seated in an unmarked and windowless room in the Nevada desert, or the naval officers gliding over the Bandar Abbas shoreline, guiding their crafts by the lights of fishing boats gently bobbing in the water below?

Professor Malekzadeh

Quite agree with you on the Elephant with Hubris metaphor.

That is how the Elephant destroyed its own efforts in that unfortunate place called Land of Lamentations.

And yet, it is not chastised one bit.