by Thomas W. Lippman

The Obama administration’s reaction to the mass executions in Saudi Arabia on New Year’s Day came in the form of a mildly worded statement issued over the holiday weekend by State Department spokesman John Kirby.

It said that the United States has:

seen the Saudi government’s announcement that it executed 47 people. We have previously expressed our concerns about the legal process in Saudi Arabia and have frequently raised these concerns at high levels of the Saudi Government. We reaffirm our calls on the Government of Saudi Arabia to respect and protect human rights, and to ensure fair and transparent judicial proceedings in all cases. The United States also urges the Government of Saudi Arabia to permit peaceful expression of dissent and to work together with all community leaders to defuse tensions in the wake of these executions.?

We are particularly concerned that the execution of prominent Shia cleric and political activist Nimr al-Nimr risks exacerbating sectarian tensions at a time when they urgently need to be reduced. In this context, we reiterate the need for leaders throughout the region to redouble efforts aimed at de-escalating regional tensions.

The statement did not indicate that the United States would take or contemplate taking any action.

The statement was not surprising. In the eight decades since Americans first arrived in Saudi Arabia to look for oil, the United states has never allowed the Kingdom’s dismal human rights record to interfere with economic or strategic business. In fact, it has been Washington’s official policy not to do so.

Making Money, Preserving Alliances

In a long policy statement distributed to all American diplomatic posts in the Arab world in 1951, the State Department said that it was in U.S. interests to foster economic development and stability in Saudi Arabia, promote its security through the sale of weapons, and “observe the utmost respect for Saudi Arabia’s sovereignty, sanctity of the holy places [of Islam] and local customs.” To further those objectives, the policy guidance said, “We should take care to serve as guide or partner and avoid giving the impression of wishing to dominate the country.”

In practical terms, that meant that the United States was engaged with Saudi Arabia to make money and to encourage the kingdom’s rigorous anti-Communism, not to tell the Saudis how to run their affairs. That was during the administration of Harry S. Truman, and every subsequent president, Democrat or Republican, has more-or-less adhered to the same policy. Even Jimmy Carter, who made human rights the cornerstone of his foreign policy, was obsequiously laudatory of his hosts when he visited Riyadh in 1978, because he wanted two important commitments from them: to restrain oil prices and to support the Egyptian-Israeli peace process, to which Carter was committed. For President George H.W. Bush, the target was Saudi cooperation in the war to drive Saddam Hussein’s Iraqi troops out of Kuwait. Presidents always want something from Saudi Arabia—for the past decade it has been help in the fight against al-Qaeda and Islamic extremism—and know they can’t get Saudi cooperation by haranguing the kingdom about its domestic affairs.

It’s not as if American officials are unaware of Saudi Arabia’s record of mass arrests, secret rigged criminal trials, restrictions on speech and association, and intolerance of any religion other than the Kingdom’s unique form of Sunni Islam. The State Department duly notes these abuses in its annual report on human rights conditions around the world as does the autonomous U.S. Commission on International Religious Freedom in its reports.

“For years, the U.S. government’s reliance on the Saudi government for cooperation on counterterrorism, regional security, and energy supplies has limited its willingness to press the Saudi government to improve its poor human rights and religious freedom record,” the commission noted in its 2015 report.

In accordance with a system created by Congress, the commission in 2004 designated Saudi Arabia a “country of particular concern” because it “engaged in or tolerated particularly severe violations of religious freedom.” Those violations include the exclusion from the Kingdom of all forms of worship other than Islam, its requirement that all citizens be Muslims, and its systematic oppression of its Shiite Muslim minority, an estimated 10-15 percent of the population. Under the law, such a designation requires the imposition of sanctions unless the president issues a waiver. Obama and his predecessor, George W. Bush, have always done so.

The United States is hardly the only country that has faced this contradiction between its professed ideals and Saudi reality. Asked about it by a television interviewer in October, British Prime Minister David Cameron replied,

We have a relationship with Saudi Arabia and if you want to know why I’ll tell you why. It’s because we receive from them important intelligence and security information that keeps us safe. The reason we have the relationship is our own national security. There was one occasion since I’ve been prime minister where a bomb that would have potentially blown up over Britain was stopped because of intelligence we got from Saudi Arabia. Of course it would be easier for me to say: ‘I’m not having anything to do with these people, it’s all terribly difficult etcetera etcetera.’ For me, Britain’s national security and our people’s security comes first.

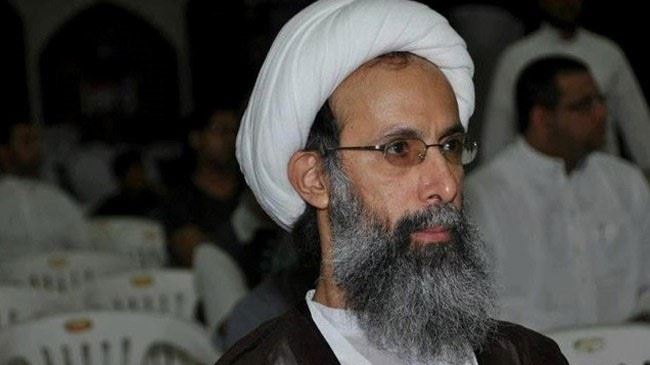

Execution of al-Nimr

As the State Department noted, the most provocative of the January 1 executions was that of Sheikh Nimr Bakr al-Nimr, a firebrand Shia theologian and activist who has long been an outspoken critic of the Saudi regime. The State Department’s concern that the execution risked “exacerbating sectarian tensions” in the region was validated almost immediately when anti-Saudi demonstrations erupted in Shia-ruled Iran and other Shia-majority communities. On Sunday, Saudi Arabia announced it was breaking diplomatic relations with Tehran, Riyadh’s chief rival for regional and religious dominance. Iran had predicted dire consequences and “divine vengeance” if Nimr were executed.

To Saudi Shiites, Nimr had become a heroic symbol of their well-documented grievances. His family issued a statement saying that

He was a shining example for peaceful and non-violent protest. He advocated personal responsibility and courageously called for the legitimate civil rights [of Saudis] and had renounced sectarianism for more than four decades. We denounce and condemn this unjust killing, which exemplifies the killing of wisdom, moderation, and betrayal of the peaceful means of protest the late Sheikh followed. He had always rejected and denounced the use of arms and violence, which is evidenced by his sermons and statements.

But Nimr he was not a peaceful activist in the style of Gandhi or Martin Luther King Jr., according to the British writer Robert Lacey, author of The Kingdom, who attended news conferences in 2007 by him and a rival Shiite leader, Sheikh Hassan al-Saffar. “The tone could not have been more different,” Lacey wrote for a membership-only news service yesterday.

Al-Saffar was conciliatory, moving, passive—quietist in a constructive fashion, anxious to emphasize the gains for the Shia community that he and his colleague Jaffr Al-Shayeb had made through engaging in dialogue with the government.

Al-Nimr was anything but quietist. He was positively incendiary—angry, inflammatory and notably uncompromising. He was contemptuous of the Al-Shayeb and Al-Saffar for playing the Saudi game, and called openly for the overthrow of the house of Saud.

Nimr had also called for Saudi Shiites to secede from the Kingdom and affiliate with nearby Shia-majority Bahrain.

Iranian threats issued in advance of the execution are likely to augment the already deep suspicions about the loyalty of Saudi Arabia’s Shiites that are prevalent among the Saudi leadership and general population. Saudi children are taught in school that Shiites are apostates and heretics. Suspicion that the Shiites are aligned with Iran will not improve their status.

For the Obama administration—and for Russia, France, and other Western powers—the immediate affect of the breach in relations between Saudi Arabia and Iran is that it will complicate their efforts to find solutions for the wars in Syria and Yemen. For Saudi Shiites and for human rights activists, the next question is what will happen to Sheikh Nimr’s nephew, Ali, who is also under a death sentence. The young man, now 20 years old, has been in prison since he was 17.

Photo: Sheikh Nimr Bakr al-Nimr

While overtly mute on Saudi Arabia’s abuses, the USA appears to covertly undermining Saudi Arabia by throwing it in situation where the country is weakened and therefore more enslaved to the USA.

Syria and Yemen are two examples where the USA has not only allowed the Saudis to intervene by financing military attacks on these countries, but has encouraged such attacks on countries that are seen as fiercely opposed to Israel and the USA hegemony in the region, namely Iran and Syria.

In that respect the USA has surely not prevented the execution of Al Nimr. It sees it as a useful provocation that would increase the tension between Iran and KSA and ideally weaken both of them. Busy in dealing with Syria, Yemen and now Saudi Arabia, Iran would therefore avoid any confrontation with Israel. Terrified KSA would throw itself further in the USA’s arms and buy more billions of weapons. Russia would be hampered in its effort to pacify Syria.

We may see more of these traps set by the USA in the region. While KSA is continuously falling into them and weakened further, Iran and Russia seem still able to deal with them calmly.

Would Russia and Iran retaliate by setting traps to the USA? What are the USA Achilleus heels?

@Virgile very good point! Hezbollah is already pissed off at Israel for Israel assassinating one of it’s military leaders last month! Hezbollah may open up another front attacking Israel to keep them in check! Iran won’t be attacking sheikdom of SA on an offensive move because of its political backlash in other Islamic countries simply because of Makkah and Medina being the most holy places for Moslems. However if Iran has to defend itself against any attack by any country, the eastern front of SA is wide open with majority Shia and where in the SA’s oil industry infrastructure is located! One of these countries in the region is going to miscalculate the situation and then ….?