via SUSRIS

SUSRIS Editor’s Note: Over the last two years the twin crises in Egypt and Syria have placed a heavy diplomatic and security burden on leaders and policymakers in the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia and the United States. Washington and Riyadh have worked closely to formulate responses to the unfolding catastrophes in these countries as well as complex national security troubles unfolding across the region. As with any bilateral relationship American and Saudi interests do not always coincide as has been displayed in the reaction to the coup and crackdown in Egypt. The prospects for a military response to the use of chemical weapons in the Syrian civil war only adds to the difficulties of forging a common approach to the new regional realities.

To provide context to these urgent issues SUSRIS called on Ambassador Chas W. Freeman, Jr., to share insight and perspective on the diplomatic consequences for Washington and Riyadh. Freeman’s distinguished career included service as US Ambassador to Saudi Arabia during Operations Desert Shield and Desert Storm and as Assistant Secretary of Defense for International Security Affairs. He was the President of the Middle East Policy Council and vice chair of the Atlantic Council of the United States. Freeman is Chairman of the Board of Projects International, Inc. We spoke with Ambassador Freeman by phone from his home in Rhode Island on August 27, 2013.

[SUSRIS] Thank you for taking time to talk about the crises in Syria and Egypt and the fallout for American ties with its allies in the region, especially the US-Saudi relationship.

All eyes have shifted from the coup and crackdown in Egypt and the American reaction to it, to the increasing likelihood that the United States will take the lead in a military response to last week’s use of chemical weapons in Syria. In what ways are there agreements and differences in the policies of Washington and Riyadh over Egypt and Syria?

[Amb. Chas W. Freeman, Jr.] There is actually a fair amount of convergence in short-term Saudi and American objectives with respect to Syria, but probably some divergence in long-term views, which we can get back to. At the moment there are serious divisions of opinion between the United States and Saudi Arabia that mainly find expression in our policies toward Egypt.

It’s no secret that the Royal Family in Saudi Arabia was shocked when the United States first vacillated and then withdrew its support from President Mubarak. This seemed to them to show that the United States was an unreliable protector. Obviously protection has been one of the services that the Saudi Royal Family has traditionally looked to the United States to provide. The Mubarak situation catalyzed Saudi reactions borne of over a decade of growing exasperation with U.S. policy. While the Saudis don’t want to give up the relationship with the U.S. – for some purposes the U.S. remains a valued partner, they have concluded that in many respects they’re on their own. They see they now have to act unilaterally in defense of their own interests, even when this puts them at odds with the United States.

Now we see a strong Saudi intervention in Egypt on behalf of autocracy. The effort to make the region safe for autocracy directly counters the American ideology of democratization. In the Saudi judgment, recent experience shows that democratization leads inevitably to the triumph of political Islam. Islamist democratism is a challenge to the legitimacy of the Saudi monarchy, which is based on the notion that in Islamic societies there is a religiously enlightened leader, an emir, who leads the Muslim community, the Ummah. While the emir’s leadership has to be responsive to opinion and political consensus, it is ultimately autocratic.

This idea contrasts with the western notion that sovereignty is or should be exercised from the bottom up through elections. So we have a fundamental disagreement on Egypt. We probably have the same disagreement, although less obviously, in the case of Bahrain. It was there that, from the Saudi perspective, the first effects of the Mubarak debacle in the Arabian Peninsula were felt.

The turmoil in Egypt has led to the emergence of some degree of entente between the Saudis and the Russians on the issue of autocracy and opposition to militant Islamist populism. The Russians see an opportunity in Egypt as the Egyptians reconsider their dependence on the United States – perhaps in part reversing the Egyptian switch to American protection that Sadat pulled off. The Russians may try to work with the Saudis, the Emiratis, and others wealthy autocracies in the Gulf to reestablish a military supply and strategic relationship with Egypt that would once again give them significant influence in the Middle East beyond Syria. This has clearly been discussed, at least in a preliminary way, between Prince Bandar bin Sultan and Vladimir Putin. So I think Saudi-American disagreements over Egypt are not trivial.

There are other sore points dating back to the invasion of Iraq. Some Saudis favored the invasion, but most at the top clearly did not. It badly backfired in terms of establishing a pro-Iranian, Shiite-dominated regime in Baghdad. The U.S. attempted for some time to broker rapprochement between Riyadh and Baghdad but I think it has now concluded this is impossible and given up.

There is also a difference in opinion between us about how much of a supporter Malaki is for the Assad regime in Damascus. And I don’t think the Saudis have lost their sympathy for the Sunni minority in Iraq or their desire to see it reestablish itself in a position of at least equality, maybe even more, in Iraqi politics.

In Syria, as I said, we have a short-term convergence of interest. We both wish to remove Syria from the asset side of Iran’s geo-strategic balance sheet. We both oppose Hezbollah. We both would both like to see Assad out. In the end, however, we may not agree about the future of Syria. The Saudis have a strong interest in the territorial integrity of Syria. The United States may not share that interest. Certainly Israel, our principle partner on these matters, does not. The Saudis may see a future Sunni-dominated Syria as a platform from which to remove Iraq from the Iranian orbit. I don’t think Americans have thought much about the implications of that.

There’s a lot of confusion and cognitive dissonance. Many things are in motion between the United States and Saudi Arabia with respect to the overall configuration of the region. The Arab uprisings were about Arabs re-seizing control of their own destiny. This began in Tunisia and Egypt and spread. It has now affected Saudi Arabia in the sense that the Saudis are also attempting to seize control of their own destiny and regional role, in both of which the US will necessarily play a diminished part.

[SUSRIS] Saudi and UAE officials were said to have warned the US Secretary of State of consequences for US ties, especially in the area of security concerns, over the question of American support for Egypt according to a Wall Street Journal article. King Abdullah warned that Saudi Arabia stood against those who tried to interfere in Egypt’s domestic affairs. You were quoted by Jim Lobe as saying, “The Al-Saud partnership with the United States has not only lost most of its charm and utility; it has from Riyadh’s perspective become in almost all respects counterproductive.” Yet, the Obama Administration engaged in weeks of verbal gymnastics to keep from calling the coup a coup and has so far only reacted with token measures against the bloody crackdown against the Muslim Brotherhood. Is there that much daylight between Riyadh and Washington on the Egypt issue to warrant such a high-pitched reaction?

[Freeman] Riyadh is very realistic. When Mubarak was removed from office there was the shock, which I described, and an absence – from the Saudi perspective – of a helpful and supportive American reaction. The Saudis embraced the new reality and tried to make the best of it, but then they saw several things happen which they didn’t like. First, in foreign policy Morsi reached out to Iran, which Saudi Arabia sees as its principle regional rival. Morsi’s government did not have the negative view of Hamas that Riyadh does. As the Morsi government proved to be incompetent, demonstrating that the Muslim Brotherhood and Islamists in general lack a coherent and effective economic philosophy or policy, Saudi Arabia saw Egypt drifting into anarchy and alignments that were contrary to its interests. Saudi Arabia very much welcomed and may even have encouraged the overthrow of Morsi. By any definition, notwithstanding the tortured legal fictions that prevail in Washington, it was a coup. The Saudis are pleased that the U.S. has not said that.

The Saudis do not want the United States to break with the al-Sisi government in Cairo. On the contrary, they would like the U.S. to support that government, as they do. Our support has been equivocal. The military aid relationship has not been solidly reaffirmed. It has been under review. Things have been moving on a case-by-case basis. American statements have — true to our values — continued to attempt to balance ideological commitments to democratization with our in interest in preserving the Camp David structure and the Egyptian cooperation with Israel, which are central to our position in the Middle East.

So we haven’t had an open break, but we’ve been very firmly warned by the Saudis. If we do suspend assistance, they will step in and repair whatever damage is done to the Egyptian Armed Forces. They have in effect deprived us of a considerable amount of leverage over the Egyptian Army.

This is the first time that I have seen so open, in fact much of any, open or concealed Saudi divergence from U.S. policy objectives. In the past the Saudi tendency has been to register objections but to refrain from undercutting U.S. policies they don’t like. Now they’re acting. And this goes back to the point I was making that they, like others, in the region have decided to take matters into their own hands.

Egypt has a history of switching sides, making dramatic readjustments in its strategic orientation. Ultimately that is what’s at stake here. The United States should exercise caution with Egypt. We could provoke a return of Egyptian strategic deference to Moscow. Of course, we’re not in the Cold War, and Russia is not our enemy. But it is a diplomatic rival, and were Egypt to return to military supply and training relationships with Russia under circumstances where the Egyptian army was running Egypt, this would have ramifications that go well beyond the question of our priority use of the Suez Canal or reliable transit rights over Egyptian airspace. I think that’s one element of this, but far from the only one.

[SUSRIS] How do the warnings from Saudi Arabia and the U.A.E. officials that security cooperation elsewhere in the region might be affected fit in here?

[Freeman] Well this is, of course, another issue. Let’s consider for a moment on a speculative basis, because that’s all it is at this point, what factors might go into a Saudi-Russian entente, maybe a Saudi-Russian entente including others in the GCC. First of all we need to remember that the strategic utility of the United States to Saudi Arabia in relation to Israel has been reduced. Our long default on peacemaking means that we are no longer on the right side of the effort to inhibit the Israel-Palestine issue’s radicalization of Arab politics. Moreover, it is obvious that we cannot control or even constrain unilateral actions by Israel against neighboring countries including, Saudi Arabia. So we don’t perform the protective roles we once did with respect to the region’s greatest military power.

Then, too, our actions in Iraq inadvertently strengthened Iran. We gave Iran a friendly and, in some respects, allied Iraq, instead of an Arab enemy that balances it. Iraq shares Iran’s interests, for example, with respect to Bahrain, which is a core Saudi security concern. We’ve also failed, from the Saudi perspective, to come up with an effective way of reversing, or even checking the growth in Iranian prestige and influence in the region. From Riyadh’s perspective, Iran is not just a nuclear issue although that’s part of it. In the case of Iran, many Saudis accuse us of errors of omission in addition to errors of commission in Iraq and Lebanon. So they don’t see us as they once did.

This brings us to Saudi and Russian interests. There are now many coincidences between them. First, both Riyadh and Moscow favor autocratic regimes. In Egypt the Russians may see an opportunity to regain influence with Saudi help. The Saudis may see an opportunity to offset objectionable American policies by either paying for or helping to arrange Russian arms transfers to replace those that we suspend or cancel. With respect to Bahrain, of course the Russians have no objection to Saudi or GCC policies. With respect to Iran, relations between Moscow and Tehran are good on a day-to-day basis but the two remain strategic rivals. Russia is in the region. It can’t come and go as we do. Russia has the potential capacity to balance Iran from the north, not in the Gulf, without the socio-political complications that our presence there entails.

Russia is also a historic rival of Turkey. Relations between Moscow and Ankara have never been better but their rivalry continues just below the surface. The Saudis are against the Turkish model of Islamist democratism and do not have an interest in advancing Turkish foreign policy objectives, especially in Egypt.

Finally, strangely enough, about twenty percent of Israelis are Russian so the Russians have some unexpended influence in Israel to bring to bear should it choose to do so. So the attractions of trying to work out a Saudi-Russian entente are there. By entente, I mean a framework for limited cooperation on a limited set of issues, perhaps for a limited period time.

There also are a lot of difficulties in the way of Saudi-Russian cooperation. Let me take one of them.

If you look at Syria the primary Saudi objective is to remove it from the Iranian orbit and undercut Hezbollah. Secondarily, they want to remove Assad from office. From the Saudi perspective, he has been dishonest, deceitful, and dishonorable. Riyadh would like to see him go and his regime with him. However, the primary objective is to eliminate Iranian influence and to undercut Hezbollah, which has emerged as the dominant political force in Lebanon, where it contests Saudi influence. There may also be a Saudi objective of using a reoriented Syria, as I suggested, to try to retake some or all of Iraq for Sunni Islam, reducing Iranian influence there.

Assad is a secondary issue. What the Russians have wanted to do in Syria in addition to protecting their commercial interests, their naval base, and their relationships with the Syrian elite, is to draw a contrast between their own stalwart support for the beleaguered Assad and the American abandonment of Mubarak. They want to show that they are a reliable protector and partner.

Syria is now de facto partitioned in many respects, and the Assad regime does not even control many of the elements that support it. In some cases they are taking on the characteristics of warlords or gang leaders, even self-financing with smuggling and extortion and protection rackets and other activities. The only way one could imagine Assad surviving after a graceful interval and being allowed to withdraw with dignity from a Syria he can no longer control is if the Saudis and the Russians cooperated to accomplish that. Depending on what was agreed, that could perhaps achieve the Saudi objective of cutting the Damascus’ ties with Tehran. It could also accomplish the Russian objective of not having Assad overthrown, but withdrawing with some dignity. This is a real long shot but not impossible to imagine.

So you could see a situation in which both sides gained from the strategic reorientation of Syria and from the orderly removal of Mr. Assad. I suspect that there will be some talk about this, although it appears the initial Saudi approach to the Russians was another effort to persuade them to do what Saudi Arabia would prefer, which is simply to get rid of Mr. Assad at the outset. That can’t have gotten very far but it is not necessarily the end of the story.

[SUSRIS] It was done in a surprisingly public way. Prince Bandar could have made his meeting with President Putin without posing for the cameras.

[Freeman] There are many games going on here, and one of them is a reminder to the United States that there’s more at stake than we tend to imagine.

[Freeman] There are many games going on here, and one of them is a reminder to the United States that there’s more at stake than we tend to imagine.

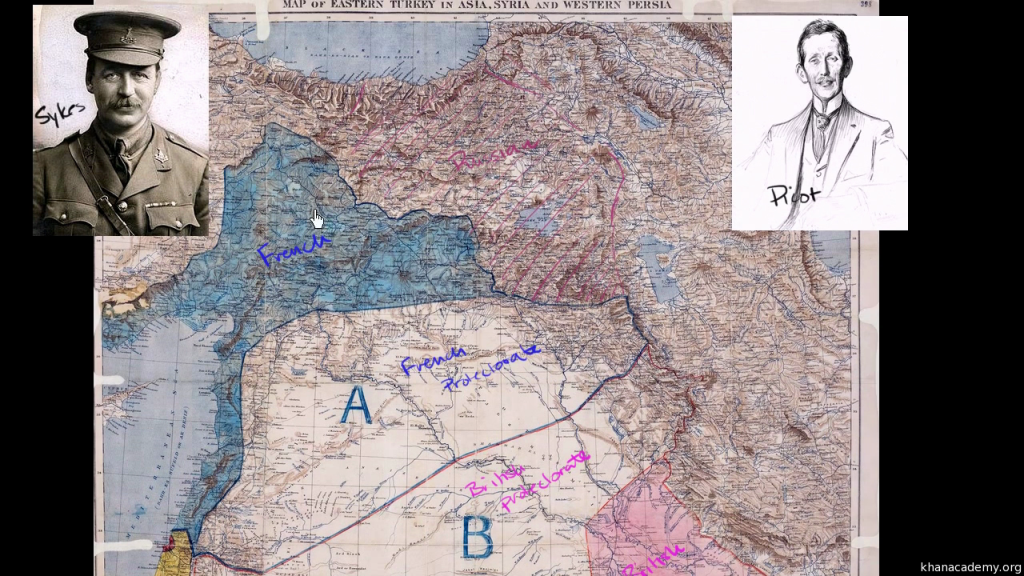

The world that has existed in the Middle East is changing. Mr. Sykes’ and Mr. Picot’s work is coming undone. Strategic orientations of the past cannot be taken for granted. Saudi Arabia itself has got its own interests and requirements for policy and cannot be taken for granted by the United States, as we’ve often tended to do.

Additionally, by going to Moscow, the Saudis undoubtedly hoped to unnerve Bashar Al-Assad and Tehran and put pressure on both.

Finally there’s another factor and that is Russia and Saudi Arabia – the two largest oil producers and exporters in the world – are concerned about how to cope with the resurgence of American production of oil and gas from shale and other unconventional sources. Apparently one of the things that was discussed was some sort of arrangement for coordination to sustain oil prices at what the two sides consider to be a reasonable level. This is another previously improbable but new and potentially significant subject for these two governments to explore.

[SUSRIS] Now that Syria has displaced Egypt in the headlines and Washington is ready to act against Assad is there likely to be a change in language about the disagreements or policy moving forward?

[Freeman] Both governments have an interest in sustaining an appearance of harmony and cooperation between them. What does it benefit either to appear to separate from the other, unless and until some major strategic deal that has advantages for one side or the other is struck? I wouldn’t expect either side to be very honest or forthcoming about what it thinks about the actions and activities of the other. Of course if the United States attacks Syria I expect the Saudis will be delighted since they have been urging a more active American support of the opposition and opposition to Assad for eighteen months anyway.

[SUSRIS] Is there a risk that a limited punitive strike, along the lines of what is being discussed, will do little to change the situation, the catastrophe that it is, and with Assad still in power?

[Freeman] Here we have to quite cynically recognize some realities. The first is that if the primary objective of both Saudi Arabia and the United States, and some other countries in the region, is to remove Syria from Iran’s embrace, then anarchy and mayhem are the next best thing to regime change.

The case has been made, most recently in the New York Times by Edward Luttwak, that the United States would lose if either side won. Therefore, the argument goes, the best thing is for the fighting to go on. Now that of course is a reminder of some of the more absurd elements of the “red line” about the use of chemical weapons. In a week where the Egyptian army killed a thousand people, the Syrian government was accused – rightly or wrongly, we don’t know – of having killed three or four hundred people, as if it was the use of the weapon involved, not the deaths that really mattered. One hundred thousand people or more have died in Syria with the United States and others doing very little of an overt nature. The international community remains divided on this subject. Some might argue that it displays an odd set of humanitarian priorities.

So, this is one set of issues. Another is that this effort to use precision strikes to alter the situation on the ground in Syria is unlikely to be effective. Look at what has happened in Syria. A very fractured opposition now confronts an increasingly fractured regime, with militias operating under local warlords or gang leaders. They are carrying on a great deal of their struggle not so much in support of the regime as in defense of the ethnic communities that depend on the regime — the Christians, the Alawites, secular groups who don’t like the Islamists who dominate the opposition.

It’s entirely possible that a strike on chemical weapons facilities would result in the degradation and devolution of control over the chemical weapons to these warlords and feudal barons, meaning that it would further dilute the government’s control of chemical weapons, and greatly increase the probability of their use by people without the knowledge or support of whatever regime remains in place in Damascus.

This is an extremely dangerous situation. Far more dangerous still is the question of what follows the Assad regime. And here is where I think the United States and Saudi Arabia may turn out to have some serious differences. The Saudi tolerance of Salafi Muslims is a great deal higher than that of the United States. After all, Saudi Arabia is officially Salafi. And while we have a common enemy in Al-Qaeda, the Jihadi elements who attack us also attack Saudi Arabia, or perhaps it’s the other way around – those who attack Saudi Arabia also attack us. To the extent there’s daylight between the United States and Saudi Arabia, their incentive to focus on Saudi Arabia rather than the United States goes down. That is to say that the probability of a Jihadi focus on the United States goes up. That would be an ironic result indeed of what I take to be an effort by the Saudis in Syria and Lebanon to reduce the danger of terrorism against their own society.

[SUSRIS] Let’s return to the U.S.-Saudi relationship. The partnership is much more complex than any one element of the security component. Let’s look at US-Saudi relations in their totality, and the history of recurring ups and downs, in the past you referred to it as being a marriage. How would you describe the playing field going forward, looking at the scope of business ties and all of the things that are held as being values in the relationship?

[Freeman] It’s a much more fluid and dynamic relationship now than it was, with many things in motion going in different directions. It’s more like a polo field than it is like the stable relationship characteristic of marriage. There are a lot of gopher holes in the field that can break the legs of the horses who are playing the game.

If you look at the various interests that have brought us together, there is the tradeoff of energy for security. As I’ve pointed out the Saudis no longer have much confidence in our ability to deliver security for them. They also see us, I suspect, as an increasingly problematic factor in global energy markets given our rapid ramp up in oil production and our gas exports. The question of cooperation on Islamic issues has been moot for quite a while. We’re very much at odds on that, although I continue to believe that under King Abdullah there have been major opportunities for us to cooperate with the Saudis in pulling the fangs of the Jihadi movement, which we have not seized. It’s a tragedy that we have not done so.

We have a continuing interest in freedom of transit through the air and sea space in the Arabian Peninsula and around it as the discussion of Egypt in the Wall Street Journal that you cited brings out. That continues on a case-by-case basis with no overall framework that guarantees it. It’s clearly related to Egyptian decisions on these matters and perhaps cannot be taken quite so much for granted as in the past.

The Saudis continue to use their connections to the United States, I think very wisely and skillfully, to expose a younger generation of lower-middle class Saudis to come to the modern culture of the United States. There’s a huge number of students here under the King’s scholarship program.

The U.S. continues to be a very significant presence in Saudi commercial markets but in terms of market share we have been a diminishing presence. In every respect we are not the destination for Saudi oil exports we once were. We’re not the source of imports we once were. Others have a greater role.

With respect to cooperation in foreign policy, the Saudis are clearly looking around for ways to dilute what they regard as over-dependence on the United States. This is not a particularly promising arena for cooperation in the short term.

Finally, cooperation on counterterrorism brings us squarely to the irony that it is in many respects Saudi closeness to the United States, and therefore to American policies on issues like the Israel-Palestine issue, that makes Saudi Arabia a target for Islamist terrorists. Therefore, the closer our cooperation, public cooperation, arguably the greater the cost it will be to Saudi Arabia in this arena. Nevertheless, we do have the same enemy, and I would expect our cooperation to continue, though perhaps with less publicity.

To sum all this up I would say that neither side can do without the other, or wants to do without the other, but the Saudis are much more prepared than in the past to reduce their reliance on the United States and to seek new partners and new directions.

[SUSRIS] Can you remember any point in American diplomatic history where there has been such a convoluted collection of circumstances as we see now in the Middle East?

[Freeman] Last fall I gave two speeches on the changing world order, one called“Paramountcy Lost” [Challenges for American Diplomacy in a Competitive World Order] the other called “Nobody’s Century” [The American Prospect in Post Imperial Times]. The key point is that it’s not just the Middle East but everywhere there is a decentralization of political and economic power. Militarily we Americans are still unmatched but in the other spheres we now have effective rivals on the regional and sometimes even on the global level.

The complexity of foreign affairs now requires a level of agility from Americans that we have not historically displayed. We’re good at wars of attrition and the diplomatic equivalent of trench warfare, not blitzkrieg.

What we are confronting now is the possibility, still just a possibility, still reversible, that the entire landscape in the Middle East that we have been accustomed to, could be rearranged by some geostrategic earthquake.

I think there is a broader context here. The Saudis are looking out for their interests first, in a way that frankly they did not in the past. The Saudi concept has been that friends defer to the interest of friends. Since the United States does not defer to anyone else’s interests these days, not surprisingly, Saudi expectations and behavior are different now. We have interests that differ from theirs. They are not treating us with the deference they once did. They are pursuing their own interests and policies. I think we need to reexamine our own interests. I think our interests dictate a strong relationship with the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia but some of the policies we have followed in the Middle East have clearly been counterproductive and others have been ineffectual. We need to rethink things.