by Giorgio Cafiero

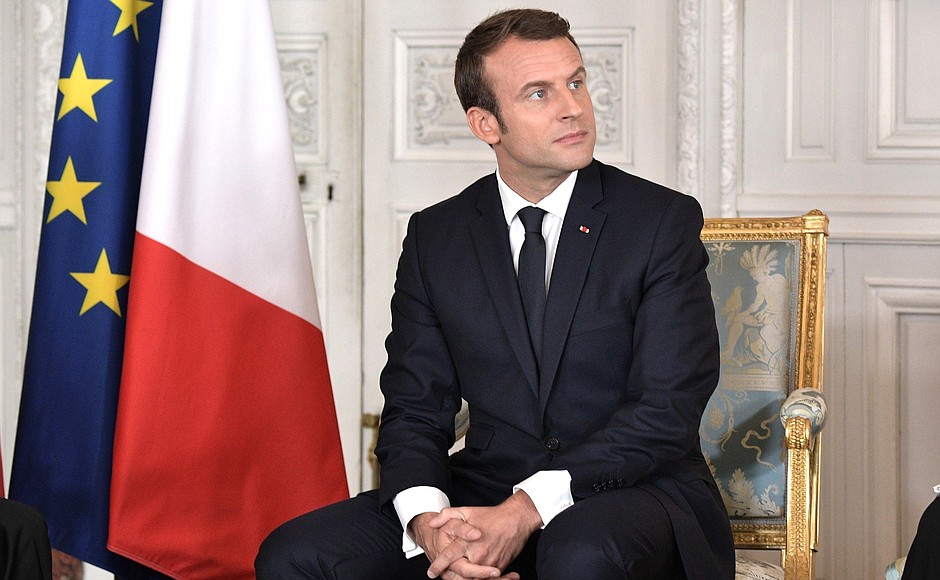

On July 2, France along with five African states – Burkina Faso, Chad, Niger, Mali, and Mauritania – launched a multinational force to confront al-Qaeda offshoots and other militant extremists in the volatile Sahel. President Emmanuel Macron said that this force will be operational “in a matter of weeks” and France will provide 70 vehicles and $9 million of funding (in addition to $57 million from the European Union). Meanwhile, these five African countries—the G5 Sahel bloc—will contribute 5,000 on-the-ground troops, as Macron put it, to “combat terrorists, thugs, murderers, whose names and faces we must forget, but whom we must steadfastly and with determination eradicate together.”

The deployment of this multinational coalition comes four-and-a-half years after Paris launched Operation Serval in early 2013, a response to several militant Islamist groups usurping control of northern Mali in 2012 amid the chaotic fallout of a military coup in Bamako in March of that year. Ansar Dine (Defenders of Faith), Al Qaeda in the Islamic Maghreb (AQIM), and Movement for Unity and Jihad in West Africa (MUJAO) were the dominant Islamist militias that seized power across northern Mali and prevented the Tuaregs from consolidating any gains from their 2012 rebellion. These three armed factions took control of 300,000 square miles of land with airports, military bases, and many natural resources.

Ansar Dine, AQIM, and MUJAO’s brutal imposition of sharia law (stoning and amputating for infidelity, theft, and tobacco use and outlawing of music) coupled with their destruction of ancient shrines in northern Mali outraged the international community. Yet throughout 2012 it seemed that the outside world was only kicking the can down the road by passively discussing a military operation without taking concrete steps to move forward.

That all changed in early 2013 once France became convinced that the militant Islamists were on the verge of invading the Malian capital and, potentially, the rest of the beleaguered West African country. In tandem with regional actors, Paris waged Operation Serval, which successfully enabled Malian and other Western African forces to retake control of Timbuktu, Gao, and other cities in northern Mali. Yet it did not entirely eradicate the militants. Instead, France’s direct military intervention merely dislodged them, as illustrated by last year’s attack on a Malian military base in Nampala, resulting in 17 deaths and 35 injuries. Other killings, plus kidnappings of Western journalists in northern Mali, which have continued since the extremists lost control of the main cities in 2013, underscore how large swathes of territory in the country remain vulnerable to such terrorist factions.

Since violent non-state actors continue to menace parts of Mali near its borders with Burkina Faso and Niger, officials in Ouagadougou, N’Djamena, Niamey, Bamako, and Nouakchott decided that cooperating within the framework of a French-backed multinational force will best enhance their shared interests in countering militant extremist groups that transit the porous borders of countries in the Sahel.

Ultimately, what is taking place is a shift in West Africa’s regional security environment with France, the former colonial ruler of the G5 Sahel bloc’s five members, acquiring an increasingly influential role. The absence of Nigeria (which would be sensible to include given that the Sahel encompasses the country’s northern territory where Boko Haram has waged terrorism for years) highlights how this recently launched multinational force is a French-backed bloc composed of Francophone countries.

France’s national interests, as opposed to those of its West African partners, drive Paris’ foreign policy in West Africa. The terrorist attacks waged by jihadists in Paris since early 2015 give France high stakes in northern Mali’s future given the potential for the country to become a platform for radical terrorist organizations to plot attacks in Europe. With the Islamic State (ISIS or IS) losing its grip on strongholds in Iraq and Syria, the risk of its fighters dispersing to parts of failed African states such as northern Mali adds to this threat perception.

With France, as opposed to African institutions such as the African Union and the Economic Community of Western African States, stepping up its role in the Sahel’s security landscape, many are arguing that Paris is pursuing a neo-colonial foreign policy to regain influence over some of its former colonies and access to Mali’s natural resource wealth. On the campaign trail, Macron indicated his sensitivities toward such sentiments and discussed beginning a chapter in France’s relationship with Africa to move beyond neo-colonial ties. For example, he created controversy when he identified France’s colonial war in Algeria as a “crime against humanity.” However, that remark earned him much praise in his country’s former African colonies.

Regardless of France’s underlying motives for financing this multinational African force and pursuing a more influential role in the tumultuous Sahel’s regional security architecture, the five members of the bloc are welcoming Paris’s support. The entire region has suffered from al-Qaeda-linked groups’ destruction, especially among certain ancient ethnic/tribal communities of West Africa that have practiced a peaceful and non-violent form of Islam for centuries and fear that their weak states can’t protect them from violent extremists.

Although these countries can turn to France for greater support while addressing the threat of militant extremists, it will ultimately be up to the West African governments and societies to win the struggle against extremism. This will require local actors to address root causes of Islamist militancy in this part of Africa, ranging from failed states to corruption to widespread poverty, food insecurity, and drought.

Indeed, although West African countries must take the lead, France and its European allies have a productive role to play in the region, yet that requires much more than a military strategy. Combatting the threat of radical Islamist groups in the Sahel depends on the international community no longer ignoring impoverished nations that have suffered from violence, corruption, and droughts for decades. Sustained efforts on the part of Western countries to provide massive development aid along with diplomatic initiatives aimed at reconciling the political differences between various Malian/West African groups that have taken up arms is necessary to foster stability and counter the menace of global terrorist networks in the Sahel.

Brighter economic prospects for young men in Mali’s north can weaken the appeal of jihadist militias that provide them a steady income while exploiting their grievances. Unfortunately, the violence and poverty are both causes and effects of the other, requiring more than just a military strategy to combat extremism in this poor region.

Strange that Giorgio Cafiero has not mentioned the French Franc Zone in his article.

It was Qaddafi’s threat to introduce a gold-backed Libyan currency that led to his downfall.

The French-led assault on Libya triggered a release of massive amounts of arms.

It is these arms which ended up in the hands of insurgents in Syria and West Africa.

My guess is that the French are only taking these actions to shore up support for their franc.

Many of the former Francophone countries still use the franc and this benefits France.

That also explains why this initiative has not been extended to English-language countries.

It may also be the case that it is designed to forestall large numbers of refugees too.

Right now, the numbers travelling across Africa via Libya to Europe is at it highest level.

A key element that the author failed to mention is that France persuaded the UN Security Council to make this 5,000 man force an official UN peacekeeping operation. That means that France is no longer footing the entire bill for security in the Sahel. The US objected meekly to the Security Council vote, but ended by supporting it. At 25%, the US will now be the chief financier of the Sahel operation, while France gets the credit.